Thermopower on the Cheap

December 21, 2012

Things are

precise in a

laboratory environment. You

weigh things out to five, or six,

decimal places, you control

temperature to a tenth of a

degree, and you mark time to the

second. Then, when the

specification for your miracle material is sent to the factory, there's

cigarette ash in the

crucible, and things are

over-annealed while the crew is on a

coffee break.

Six Sigma supposedly fixed most of these problems in the better companies, but

scientists are never surprised when laboratory properties are not reproduced in commercial material.

As I wrote in a

previous article (Coal, July 23, 2012), this isn't a problem for some materials, since they're just dug out of the ground and used in their pristine state. The most important of these is

coal, and if we didn't have coal, we wouldn't have had the

Industrial Revolution.

Another example is

kieselguhr, also known as

diatomaceous earth. This material, the

fossil shells of

diatoms, is a useful mixture of

silica (SiO

2, 80-90%),

alumina (Al

2O

3, 2-4%) and

iron oxide (Fe

3O

4, 0.5-2%). This nice mix of

inorganic oxides makes diatomaceous earth a good material for

thermally insulating high temperature

furnaces.

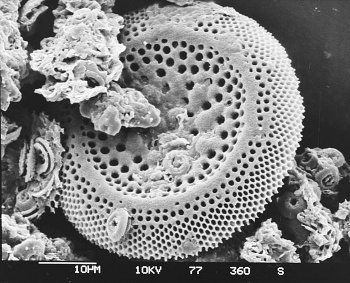

A diatom fossil from a sediment core of the Deep Sea Drilling Project.

Diatom fossils are just a few tens of micrometers in size.

Micrograph by Hannes Grobe, the Alfred Wegener Institute, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Diatomaceous earth is used as an

abrasive, as a

filtration medium, a

support medium for

catalysts, and a

filler for

plastics. The

absorbency of diatomaceous earth makes it useful for

cat litter, and also as a way to stabilize

nitroglycerin to form

dynamite.

Diatomaceous earth is about as close to a

free lunch as a

materials scientist can get, and it makes you wonder what other things might be made from other inexpensive minerals. A team of scientists from

Michigan State University and

UCLA has just developed a

thermoelectric material based on an inexpensive mineral known as

tetrahedrite.[1-2]

Tetrahedrite, one of the most abundant minerals, has the

chemical formula, (

Cu,

Fe)

12Sb

4S

13. As can be seen from the formula unit, it exits in both

copper-rich and

iron-rich forms, and

bismuth (Bi) is known to substitute for the

antimony (Sb). All this can be expected from the

atomic radii of the atoms (Cu = 135 pm; Fe = 140 pm; Sb = 145, Bi = 160), although bismuth is a tight fit. The mineral takes its name from its

tetrahedron-shaped crystals.

I've written about thermoelectric materials in several previous articles, most recently concerning the power source of the

Curiosity rover (

Curiosity Rover Power, November 5, 2012). Thermoelectric materials make use of the

Seebeck effect to convert a temperature differential to

electric power.

Thermocouples, as used for temperature measurement, do this same trick, but not very

efficiently. thermoelectric devices are constructed from

junctions of

n- and

p-doped semiconductors (see figure), but the leading material for this purpose,

bismuth telluride, is still relatively

inefficient.

A thermoelectric cell.

Bismuth and tellurium, common material components in such cells, are mildly toxic.

(Image by author, rendered using Inkscape.)

Says

Donald Morelli, a

professor of

chemical engineering and materials science at Michigan State University and leader of the research team,

"Typically you'd mine minerals, purify them into individual elements, and then recombine those elements into new compounds that you anticipate will have good thermoelectric properties... But that process costs a lot of money and takes a lot of time. Our method bypasses much of that."[2]

Their material is quite unlike the typical thermoelectric material, which is composed of rare elements and demands careful

doping to achieve high efficiency.[1] In fact, the research team was able to use natural tetrahedrite, itself, to make inexpensive thermoelectric devices; however, small chemical modifications produced highly efficient thermoelectric materials.[2]

It's reported that the

dimensionless figure of merit of this material is near unity,[1] which puts it on par with the best thermoelectrics available (see figure). This research was supported by the

Office of Science of the

U.S. Department of Energy.[2] Thermoelectric modules are commercially available, so you can experiment with this technology yourself.[3]

Figure of merit for a representative thermoelectric material (Copper-dispersed Bi0.5Sb1.5Te3.

(US Government Image, I.H. Kim, S.M. Choi, W.S. Seo and D.I. Cheong, Nanoscale Research Letters, 2012.)

![]()

References:

- Xu Lu, Donald T. Morelli, Yi Xia, Fei Zhou, Vidvuds Ozolins, Hang Chi, Xiaoyuan Zhou and Ctirad Uher, "High Performance Thermoelectricity in Earth-Abundant Compounds Based on Natural Mineral Tetrahedrites," Advanced Energy Materials, vol. 2, no. 11 (November, 2012), DOI: 10.1002/aenm.201200650.

- Energy savings - easy as dirt, heat, pressure, Michigan State University Press Release, November 27, 2012.

- Thermoelectric Power Generation Products, Tellurex Corporation.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Arithmetic precision; laboratory; weight; decimal; temperature; Celsius; degree; second; specification; cigarette ash; crucible; annealing; coffee break; Six Sigma; scientist; coal; Industrial Revolution; kieselguhr; diatomaceous earth; fossil; shell; diatom; silica; alumina; iron oxide; inorganic; oxide mineral; oxide; thermal insulation; furnaces; sediment core; Deep Sea Drilling Project; micrometer; Hannes Grobe; Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research; Wikimedia Commons; abrasive; filtration; catalyst support; support medium; catalysis; catalyst; filler; plastic; absorption; absorbency; cat litter; nitroglycerin; dynamite; free lunch; materials science; materials scientist; Michigan State University; University of California, Los Angeles; UCLA; thermoelectric effect; thermoelectric; tetrahedrite; chemical formula; Cu; Fe; copper; iron; bismuth; antimony; atomic radius; tetrahedron; Curiosity rover; Seebeck effect; electric power; thermocouple; energy conversion efficiency; junction; n-type semiconductor; p-type semiconductor; semiconductor; bismuth telluride; bismuth; tellurium; toxic; Inkscape; Donald Morelli; professor; chemical engineering and materials science; doping; dimensionless figure of merit; Office of Science; U.S. Department of Energy.