Martian Brickwork

May 29, 2017

Many words have an aura of strangeness to very young

children who know the meaning of so few words. As our

vocabularies increase, words become less strange, but there is the occasional surprise. While taking an

American history course in

high school, I read a document containing the strange word, "

brickbat." A brickbat, as you would surmise, is a piece of

brick used as a

weapon. Since our

modern world has far better weaponry, the term presently means a highly critical or

insulting remark.

Brick is a common

building material whose use goes back many millennia. The earliest bricks, which were sun-dried blocks of

clay called

mudbrick or

adobe, have been dated to about 7,500

BC, and they are very

durable in

dry climates.

Fired brick, formed by

heating such materials in a

kiln, was first

manufactured at about 3,000 BC. Primitive brick manufacture involved such processes as having

oxen mix the clay by trampling it.

There are various ways of stacking brick to make a wall, as shown by these cross-sections of various types of bricks walls common in 1928.

(Fig. 5 of Ref. 1, redrawn using Inkscape.)[1]

Aside from the notable exceptions of some works of

Lucretius (99BC-55BC),

Pliny the Elder (23-79), and

Vitruvius (c. 75BC-c.15BC), the

Romans were more interested in

engineering than

science.[2] One

technical area in which the Romans excelled was

civil engineering, which included the use of

concrete and brick. I wrote about Roman concrete in a

previous article (In Search of... Ancient Concrete, July 1, 2013).

Roman brick was originally mudbrick, but development of the fired brick technology of the

Greeks started in the

Roman Empire at the time of

Augustus, and it became a dominant technology in the

1st century. As the Roman Empire expanded, so did the knowledge of making bricks.

Today, a brick is usually made from a

mixture of the

ingredients listed below, pressed in an

hydraulic press, and fired at about 900–1000

°C. A house brick in the

United States has a standard size of 7-5/8" x 3-5/8" x 2-1/4" (194

mm x 92 mm x 57 mm). After firing, the material is an

hydrated aluminosilicate.[3]

Silica, 50-60 wt-%

Alumina, 20-30 wt-%

Lime, 2-5 wt-%

Iron oxide, ≤7 wt-%

Magnesia, <1 wt-%

While working at the University of Pittsburgh, I discovered that most Pittsburgh houses are built of brick. This is a reaction to a devastating fire in the city in 1845 that destroyed more than a thousand wooden buildings.

Brick walls are often aesthetic, as shown by this photo of a portion of a brick wall at the National Shrine of the North American Martyrs, Auriesville, New York.

(Photo by the author.)

Mars is an inhospitable place to live. In my

novel,

The Alchemists of Mars, a band of

humans survived on Mars for hundreds of years by living underground. Since Mars has been devoid of

water in its recent history, there's no abundance of Martian

caves as there is on

Earth, so these humans needed to dig their own cave. Fortunately, they were assisted in this by their

alchemical arts.

A team of

engineers and

materials scientists at the

University of California-San Diego (La Jolla, California) has suggested that humans might build their own Martian caves in the form of brick houses. Their

experiments of making bricks by the simple

compaction of a simulated Martian

regolith (soil) has just been

published as an

open access article in

Scientific Reports.[4-5]

Much of the characteristically red Martian soil consists of

nanoparticulate iron oxides and

iron oxyhydroxides.[4] A widely used Martian soil simulant,

Johnson Space Center Mars-1a, is composed of a

basaltic body coated with these oxides.[6] The major components of Martian surface soil and the Mars-1a simulant are shown in the table.

| | Component | Mars regolith (Wt-%) | Mars-1a (Wt-%) |

| | SiO2 | 45.41 | 43.48 |

| | Fe2O3 & FeO | 16.73 | 16.08 |

| | MgO | 8.35 | 4.22 |

| | CaO | 6.37 | 6.05 |

When you're dealing with a very long and expensive

supply chain, it's important to make best use of the materials at hand. The San Diego approach to making Martian bricks is important, since it avoids the addition of other materials, and it relies on compaction, alone, without firing. Previous approaches required the use of

binder agents transported from Earth, and firing in

nuclear-powered brick kilns.[4-5] Mars does contain some

organic compounds, but complex

chemistry would be need to transform these into binding polymers.[5]

Many discoveries happen by

accident. The San Diego engineers started examining how small a quantity of binding

polymer might be needed to make Martian bricks, and they discovered that no binding polymer was needed.[5] While basaltic particles will not bond together without heating, the surface oxides of the basaltic core nanoparticles form strong

bonds.[4]

An important step was enclosure of the material in a

flexible container, a

rubber tube, for compaction. This allowed movement and reorientation of the individual nanoparticle grains. Another was compaction at a high enough

pressure, equivalent to a 10

pound weight dropped from one

meter (on Mars, the drop would need to be somewhat larger).[4-5]

Photographs of brick processing from simulated Martian soil. Left, a brick made of Martian soil simulant, compacted under pressure without any additional ingredients or firing. Middle, a brick after strength testing. Right, soil, compacted in a cylindrical, flexible rubber tube before being cut into bricks.(Left, center, and right images by the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering.)

Small soil

cylinders, about an

inch tall, are produced by the

laboratory-scale process, and these were cut into brick shapes.

Microscopic examination showed that the iron oxide particles had clean, flat

facets that easily bonded to each another under compaction.[5] The strength of the brick, in the range 30-50

MPa, was found to exceed that of

steel-reinforced concrete.[4-5] Martian

colonists need not form bricks, since structures can be built additively by putting down a layer of soil, compacting it, then repeating the process.[5] The

gas permeability of compacted samples was of the order of 10

-16 m

2, which is near the value for solid

rock.[4]

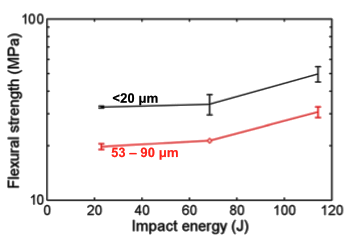

Flexural strength of a bricks made from simulated Martial soil as a function of impact energy. Two different particle sizes were used, with smaller particles giving higher strength.

(Image of fig. 3-A of ref. 4, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.)[4)]

The next task is to increase the size of the bricks.[5] This research was

funded by

NASA.[4]

References:

- A.H. Stang, D.E. Parsons, and J.W. McBurney, "Compressive Strength of Clay Brick Walls, Report RP-108, May 11, 1928, Bureau of Standards Journal of Research, vol. 8, pp. 507-571 (9 MB PDF File).

- Mark Cartwright, "Roman Science," the Ancient History Encyclopedia, September 6, 2016.

- B.C. Punmia, Ashok Kumar Jain, and Arun Kr. Jain, "Basic Civil Engineering,"Laxmi Publications (New Delhi, 2004), ISBN-13: 978-8170084037, p.33.

- Brian J. Chow, Tzehan Chen, Ying Zhong, and Yu Qiao, "Direct Formation of Structural Components Using a Martian Soil Simulant," Scientific Reports, vol. 7, Article no. 1151, April 27, 2017, doi:10.1038/s41598-017-01157-w. This is an open access article with a PDF file available at the same URL.

- Engineers investigate a simple, no-bake recipe to make bricks from Martian soil, University of California-San Diego Press Release, April 27, 2017.

- H. A Perko, J.D. Nelson, and J.R. Green, "Mars Soil Mechanical Properties and Suitability of Mars Soil Simulants," ASCE Journal of Aerospace Engineering, vol. 19, no. 3 (July, 2006), pp. 3-176, doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0893-1321(2006)19:3.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Child; children; vocabulary; History of the United States; American history; course; high school; brickbat; brick; weapon; modern history; modern world; insult; insulting; building material; clay; mudbrick; adobe; Anno Domini; BC; tough; durable; arid; dry climate; fired; heat; heating; kiln; manufacturing; manufacture; ox; oxen; mixture; mix; brick; wall; cross-section; Inkscape; Lucretius (99BC-55BC); Pliny the Elder (23-79); Vitruvius (c. 75BC-c.15BC); Roman Empire; Romans; Roman technology; engineering; science; technology; technical; civil engineering; concrete; Roman brick; Ancient Greece; Greeks; Augustus; 1st century; ingredient; hydraulic press; celsius; United States; millimeter; mm; hydrate; hydrated; aluminosilicate; silicon dioxide; silica; aluminium oxide; alumina; lime; iron oxide; magnesium oxide; magnesia; University of Pittsburgh 1845; aesthetic; National Shrine of the North American Martyrs; Auriesville, New York; Mars; novel; The Alchemists of Mars; human; water; cave; Earth; alchemy; alchemical; materials science; materials scientist; University of California-San Diego (La Jolla, California); experiment; soil compaction; regolith; scientific literature; publish; open-access journal; Scientific Reports; nanoparticle; nanoparticulate; iron oxyhydroxide; Johnson Space Center; basalt; basaltic; SiO2; Fe2O3; FeO; magnesium oxide; MgO; calcium oxide; CaO; supply chain; binder; nuclear reactor; nuclear-powered; organic compound; chemical reaction; chemistry; serendipity; accident; polymer; chemical bond; deflection; flexible; container; rubber; hose; tube; pressure; pound weight; meter; process; processing; Mars; Martian; soil; Charpy impact test; strength testing; cylinder; cylindrical; UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering; inch; laboratory-scale; microscope; microscopic; facet; pascal; MPa; reinforced concrete; steel-reinforced concrete; colonist; gas permeability; rock; flexural strength; function; toughness; impact energy; Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license; funded; NASA.