The Future of Work

March 3, 2016

In the name of

corporate unity,

industrial scientists have been subjected to the same

management fads as their non-scientist

colleagues. I was subjected to more than one of these in my career, the most notable being

Total Quality Management (TQM).

One of the objects of Total Quality Management was to reduce everything to a

process, the idea being that even an

idiot can do the right thing if he or she follows a step-by-step

procedure. Apparently, corporate

management did not have too high a regard for its

employees if they needed things to be

idiot-proof.

While detailed procedures are useful in some

scientific areas, such as

analytical chemistry, a

scientist's life is typically far from routine. In general, it's the times that you say, "Why did that happen?," that lead to advances in your field. That's why TQM was not really applicable to corporate

labs. In the rest of the corporation, employees resisted this effort to treat them as mere

automatons, interchangeable with any other employee.

Human automatons.

Humans are just another type of interchangeable part in this 1913 image of the first moving assembly line, at a Ford Motor Company plant in Highland Park, Michigan.

(Via Wikimedia Commons.)

Automation has been pushing the workforce from the other direction. Instead of turning employees into

robots, why not just replace them with robots? Automated manufacturing was championed by the

automotive industry, principally because the

United Auto Workers union was very effective at obtaining a decent

wage for its members. When employee wages and

benefits are instead channeled into automation, the results are impressive, as shown in

this YouTube video.

Long before the

Sorcerer's Apprentice attempted to use automation to fetch

pails of

water, to disastrous consequence,

Aristotle had the idea that automated

looms and

musical instruments would displace

weavers and

musicians (see figure). In the early

20th century,

James Joyce mused in

Ulysses (1922) that workers were not really

displaced by automation, they were merely

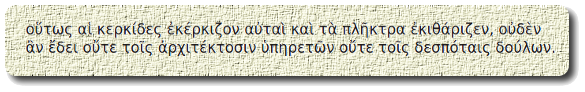

replaced by those who built the automatons.

Portion of Aristotle's Politics, Book I, Part IV, dealing with automation. "If, in like manner, the shuttle would weave and the plectrum touch the lyre without a hand to guide them, chief workmen would not want servants, nor masters slaves." (Via Perseus Digital Library.[2]

Despite

pretensions to the contrary, it might be difficult and time consuming to retrain a

busman to be a

computer programmer.

John Maynard Keynes wrote about this dark side of automation, which he called "

technological unemployment," in his 1930 essay, "Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren."[3] Such programmed unemployment reminds me of how

economists of

my generation wrote that the true purpose of

college is as a holding pen to keep people out of the workforce.

This must be a traditional pose for English academics. (Left image, a 1934 caricature of Keynes by David Low, and right image, a photograph of mathematician, G.H. Hardy, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Aside from this anticipated glitch, Keynes believed that mankind was on its way to a

post-scarcity economy.

"Thus for the first time since his creation man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem-how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure, which science and compound interest will have won for him, to live wisely and agreeably and well."[3]

In

post-war America, everything was looking rosy, and articles were published about shortened

work weeks and the problem of what we should do with all our leisure time. There were even articles warning of

depression and

suicide for those whose only purpose in life is

work.

Husbands and

wives of the

1960s were taking up

hobbies and

handicraft as a cushion against the inevitable.

The average American worker is about four times more

productive today than he was in 1950, but why hasn't this translated into ten hour work weeks? One problem is that

wealth is not being distributed uniformly. While this is known

colloquially as the problem of the

one-percenters, there's actually a

quantitative estimate of this effect. The

Gini coefficient is a representation of

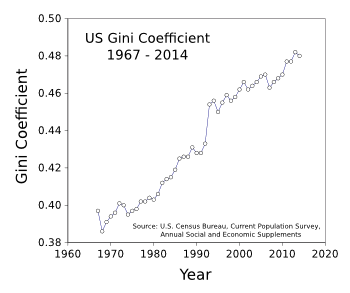

wealth inequality for which 0 is perfect equality and 1.0 is perfect inequality (see graph).

The Gini coefficient for the United States has shown a steady increase from 1967-2014.

A coefficient of 0 specifies perfect equality, while a coefficient of 1.0 specifies perfect inequality.

(Graphed from US Census Bureau data using Gnumeric.)[4])

Whether or not the unemployed might be happily unemployed sometime in the future, there's no argument that the pace of job loss to automated processes has accelerated. What's significant is that articles on this topic are appearing in the

technical literature.[5-8]

Moshe Y. Vardi,

editor-in-chief since 2008 of the

Communications of the ACM, the flagship publication of the

Association for Computing Machinery (ACM), has just presented his assessment of the matter at the

2016 annual meeting of the

American Association for the Advancement of Science.[6]

The short summary of his talk is that

computing machines will be capable of doing almost any job that a human can within 30 years.[6,8] Vardi also highlights the need for

computer scientists to consider whether the

global economy can adapt to more than 50% unemployment.[6] Says Vardi,

"We are approaching a time when machines will be able to outperform humans at almost any task... I believe that society needs to confront this question before it is upon us: If machines are capable of doing almost any work humans can do, what will humans do?"[6]

Moshe Vardi

Just as the military insider, Dwight Eisenhower, warned us about the military–industrial complex, computing insider, Moshe Vardi, is warning us about the replacement of human labor by automation.

(Rice University Image.)

(P.S. Love that tie!)

As someone who knows well the possibilities of computer automation, Vardi notes that advancement in

artificial intelligence and robotics is accelerating, and that such technologies have eliminated middle-class jobs, the process that's the cause of income inequality.[5-6] While automation can benefit humans, Vardi doesn't believe that a life of leisure is really what people want.[6-7] "I believe that work is essential to human well-being."[6]

When Keynes considered advancing automation, he imagined that people would work merely 15 hours a week by 2030, a date conveniently a hundred years after the time of his writing.[3] Vardi, however, thinks that even 15 hours is an over-estimate of what may happen. He also foresees that our economic system will need a vast restructuring to allow for the billions who will need to live a life of leisure.[7]

All this change will happen quite quickly. Vardi, in warning to his computer brethren, writes,

"It is time, I believe, to put the question of these consequences squarely on the table. We cannot blindly pursue the goal of machine intelligence without pondering its consequences."[7]

References:

- New BMW 5 Series Sedan Assembly Line, YouTube video by eurocarnews.com, November 25, 2009.

- Aristotle, "Politics," W. D. Ross, Ed., Clarendon Press (Oxford, 1957), via the Perseus Digital Library, Gregory R. Crane, Ed., Tufts University

- John Maynard Keynes, "Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren (1930)," from Essays in Persuasion, W.W.Norton & Co. (New York, 1963), pp. 358-373 (PDF File).

- United States Census Bureau, Historical Income Tables: Income Inequality, Table H-4.

- Moshe Y. Vardi, "Is Information Technology Destroying the Middle Class?," Communications of the ACM, vol. 58, no. 2 (February, 2015), p. 5, doi:10.1145/2666241.

- When machines can do any job, what will humans do? Rice computer scientist Moshe Vardi: Human labor may be obsolete by 2045, Rice University Press Release, February 13, 2016.

- Moshe Y. Vardi, "The Consequences of Machine Intelligence - If machines are capable of doing almost any work humans can do, what will humans do?," The Atlantic, October 25, 2012.

- Catherine Matacic, "How to know if a robot is about to steal your job," Science, February 14, 2016, DOI: 10.1126/science.aaf4066.

- Mary L. Gray, "Your job is about to get 'taskified'," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, February 14, 2016.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Corporation; corporate; research and development; industrial scientist; management fad; colleague; Total Quality Management; business process; idiot; standard operating procedure; management; employee; idiot-proof; science; scientific; analytical chemistry; scientist; laboratory; lab; automaton; human; interchangeable part; assembly line; Ford Motor Company; factory; plant; Highland Park, Michigan; Wikimedia Commons; robot; automotive industry; United Auto Workers; trade union; wage; employee benefit; YouTube video; Sorcerer's Apprentice; bucket; pail; water; Aristotle; loom; musical instrument; weaving; weaver; musician; 20th century; James Joyce; muse; Ulysses; Aristotle's Politics; Perseus Digital Library; Code.org; bus driver; busman; computer programmer; John Maynard Keynes; technological unemployment; economist; baby boomer; college; tradition; traditional; human position; pose; English people; academia; academic; caricature; David Low; mathematician; G.H. Hardy; post-scarcity economy; economic; leisure; compound interest; World War II; post-war; United States; America; working time; work week; depression; suicide; job; work; husband; wife; 1960s; hobby; handicraft; productivity; productive; wealth; colloquialism; colloquial; one-percenter; quantification; quantitative; approximation; estimate; Gini coefficient; economic inequality; wealth inequality; United States Census Bureau; Gnumeric; technology; technical; literature; Moshe Y. Vardi; editor-in-chief; Communications of the ACM; Association for Computing Machinery; 2016 annual meeting; American Association for the Advancement of Science; computer; computing machine; computer scientist; world economy; global economy; military; Dwight D. Eisenhower; military–industrial complex; Rice University; necktie; artificial intelligence.