Four Square Theorem

September 7, 2011

It seems that every

educated person has heard of

Fermat's Last Theorem, although it's likely that only the

mathematically-minded can state what it is. As I wrote in a

previous article (You Can Get There From Here, March 26, 2008), Fermat's Last Theorem simply states that for

integers n>2, the

equation,

an + bn = cn

has no solutions other than a=b=c=0.

Princeton University mathematicians

Andrew Wiles and

Richard Taylor proved the theorem was true in 1994, more than 350 years after it was stated. The

conjecture was stated by Pierre de Fermat in 1637, famously in the margin of a copy of

Arithmetica by

Diophantus. Fermat claimed he had a proof that was too large to fit in the margin.

There's a distant cousin to this theorem that's found also in Arithmetica. It's not quite as difficult.

Lagrange proved it in 1770, and an

undergraduate mathematics major can understand the short proof, which can be found

here. It's called

Lagrange's Four-Square Theorem, and it's simply the fact that every positive integer

n can be written as the sum of four

squares; that is,

n = a2 + b2 + c2 + d2,

where

a,

b,

c and

d are integers. Sometimes the qualification, "at most, four squares," is used. If we allow the square of zero, that qualification isn't needed.

Joseph Louis Lagrange

Lagrange is known for much more than his mathematics. He's well known to physicists for the Lagrangian; and to astronomers for the Lagrangian points, to name just two.

(Via Wikimedia Commons))

Surprisingly,

Euler was not able to prove the theorem himself, although he contributed a piece called the

four-square identity.

As usual, the theorem started as a conjecture. The conjecture, called Bachet's conjecture, was stated by

Claude Gaspard Bachet de Méziriac, a

French mathematician and

classics scholar, who translated Diophantus' Arithmetica, with commentary, from

Greek to

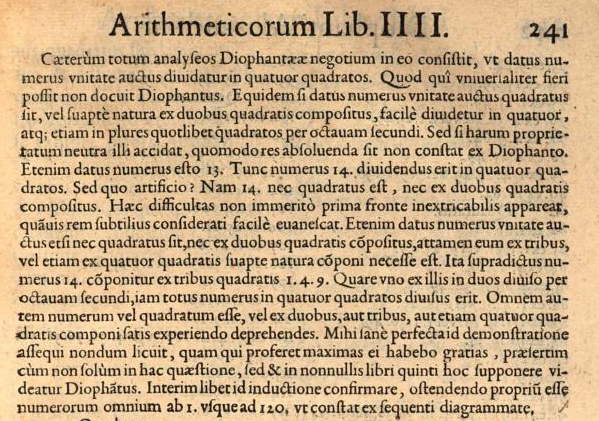

Latin in 1621. A portion of the section of the book that describes the conjecture appears below.

Diophantus Arithmetica, Latin translation by Bachet, 1621, top of page IIII-241. (Via Google Books).[2].

The last line in the figure reads,

Interim libet id inductione confirmare, ostendendo propriu esse numerorum omnium ab 1 usque ad 120, ut constant ex sequenti diagrammate.

In the mean time I want to confirm this by induction, specifically by showing it for all of the numbers from 1 to 120, as is evident from the following table. (My translation)

Bachet then presents a table of examples for all numbers from 1 - 120 that includes the following:

28 = 12 + 12 + 12 + 52

28 = 12 + 32 + 32 + 32

28 = 22 + 22 + 22 + 42

48 = 42 + 42 + 42

48 = 22 + 22 + 22 + 62

60 = 12 + 12 + 32 + 72

60 = 12 + 32 + 52 + 52

60 = 22 + 22 + 42 + 62

112 = 22 + 22 + 22 + 102

112 = 22 + 62 + 62 + 62

112 = 42 + 42 + 42 + 82

120 = 22 + 42 + 102

In 1798,

Adrien-Marie Legendre advanced the theorem by a partial proof that only three squares are needed to represent a positive integer,

if, and only if, the integer is not of the form 2

2k(8m + 7), where k and m are positive integers.

Gauss plugged a gap in Legendre's proof.

One very interesting

discovery was made by

Jacobi, who found that the number of ways a positive integer n can be represented as a sum of four squares is eight times the sum of the divisors of n, for odd n, and 24 times the sum of the odd divisors, for even n. Note that in order to get Jacobi's count, the numbers being squared can be negative, and you need to count all combinations of numbers; that is,

1 = 12 + 02 + 02 + 02

1 = 02 + 12 + 02 + 02

1 = (-1)2 + 02 + 02 + 02

etc...

References:

- Eric W. Weisstein, "Lagrange's Four-Square Theorem," MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource.

- Claude Gaspar Bachet, translator: "Diophantus of Alexandria, Arithmetica," 1621, via Google Books.

Permanent Link to this article

Linked Keywords: Liberal arts; Fermat's Last Theorem; mathematics; integer; equation; Princeton University; Andrew Wiles; Richard Taylor; conjecture; Arithmetica; Diophantus; Lagrange; undergraduate; Lagrange's Four-Square Theorem; square; Lagrangian; Lagrangian point; Wikimedia Commons; Euler; four-square identity; Claude Gaspard Bachet de Méziriac; French; mathematician; classics; Greek; Latin; Google Books; Adrien-Marie Legendre; if, and only if; Gauss; Jacobi's four-square theorem; Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi; Eric W. Weisstein.