Is eπ > πe?

January 22, 2024 During my high school years, the slide rule was the weapon of choice for calculation in science. The modern slide rule has its origin in Napier's rods. These rods were engraved with a logarithmic scale, and sliding one along another was a means to add or subtract logarithms, thereby doing multiplication or division. When greater precision was required, the usual recourse was using values from a table of logarithms. Slide rules were also engraved with scales for finding values of trigonometric and other useful functions.

Mid-twentieth century computing device - The slide rule. The more expensive slide rules were crafted from bamboo. Mid-priced units were aluminum. Most students had plastic versions, such as the one pictured. (Photograph by Roger McLassus, via Wikimedia Commons. Click for larger image.)

When I reached college, simple electronic calculators became available. These were called four-bangers, since they could only add, subtract, multiply, and divide, and they fell short of an engineer'ss and scientist's ideal calculator requirements. Eventually some very expensive scientific calculators came into the market. When a National Semiconductor scientific calculator became available for slightly more than $100, this became my first scientific calculator. Finally, as a corporate research scientist I was able to get a HP-33C Scientific Programmable Calculator (see image) for analysis of xray diffraction data. This calculator cost about a hundred dollars when purchased in 1980. This is $375 in today's money, but an equivalent calculator can now be purchased for less than fifteen dollars.

I've retained my HP-33C Scientific Programmable Calculator, no longer working, as a keepsake.

This calculator had a display with an eight digit mantissa and two digit exponent formed from red light-emitting diodes.

Nobel Physics Laureate, Kenneth G.Wilson (1936-2013), about whom I wrote in an earlier article (Kenneth G. Wilson, June 21, 2013), remarked about his purchase of an HP pocket calculator.

"I buy this thing and I can't take my eyes off it, and I have to figure out something that I can actually do that would somehow enable me to have fun with this calculator."[1]

(Photo by author.)

Now to the topic of this article, whether eπ is greater than πe. The mathematical constant e is the base of natural logarithms, and it has a value of about 2.71828. The mathematical constant, π, also called Archimedes' constant, is the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter, about 3.14159. Using an electronic calculator or a spreadsheet is an easy way to answer this question; viz.,

eπ = 23.14069...A mathematician would scoff at such a crude resolution of the question, since no proof is involved. An article by Presh Talwalkar gives a few such proofs, most of which throw a lot of mathematics at the problem.[2-3] However, one such proof involving a Taylor series expansion is simple; so, I'll give it here. The Taylor series expansion of ex is

πe = 22.45915...

ex = 1 + x + x2/2! + x3/3! + ...In a series such as this, when x is positive, we know that the partial sum of any number of the leading terms will always be less than the value of the full series; thus,

ex > 1 + xIf we select as our value for x, (π/e - 1), we find that

eπ/(e - 1) > (π/e - 1) + 1since

(π/e - 1) + 1 = π/eand

e-1 = (1/e)we have

(1/e) eπ/e > π/eand

eπ/e > πThen, raising both side of the inequality to the power of e,

eπ > πeAnd, as they say, quod erat demonstrandum (QED). A recent paper on arXiv by Andrés Vallejo and Italo Bove of the Universidad de la República (Montevideo, Uruguay) gives a different proof of this proposition.[4] This solution is based on the second law of thermodynamics, the entropy law.

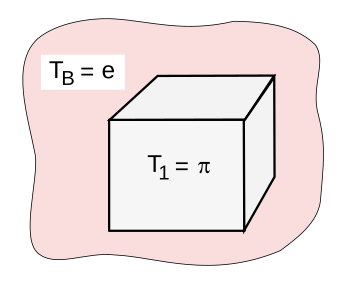

The thermal environment for the thought experiment demonstrating that eπ > πe. (Created using Inkscape)

The thought experiment demonstrating that eπ > πe is based on the thermal environment shown in the figure. An incompressible solid A with a constant heat capacity C is initially at the temperature T1 = π. It's immersed in a large thermal reservoir B at temperature TB = e. Equilibrium is reached when the temperature of the solid equals the temperature of the reservoir, at which point the entropy change of the solid is simply computed.

ΔSA = C ln(T2/T1) = C(1 − ln(π))Thermal equilibrium of the reservoir and solid is achieved by exchanging heat Q and energy U.

QB = −QA = −∆UA = C(T1 - T2) = C(π − e)The entropy change of the reservoir and the total change of entropy of the system are calculated.

∆S = QB/TB = C(π/e - 1)

ΔStotal = ΔSA + ΔSBAccording to the second law of thermodynamics, the total entropy change must be positive.

ΔSA + ΔSB = C[(π/e) - ln(π)]

π/e − log(π) ≥ 0 =>Then, by making both sides of the inequality a power of e, we get.

π ≥ log(πe)

eπ > πe

References:

- Martin Weil, "Kenneth Wilson, Nobel winner who explained nature's sudden shifts, dies in Maine at 77," Bangor Daily News, June 19, 2013.

- Presh Talwalkar, "Monday puzzle: what is greater: e^pi or pi^e?," MindYourDecisions Blog, August 5, 2013.

- Comparing pi^e and e^pi without calculating them, Mathematics Stack Exchange, Oct 26, 2010.

- Andrés Vallejo and Italo Bove, "Which is greater: eπ or πe ? An unorthodox solution to a classic puzzle," arXiv, September 9, 2023, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2309.10826.