Length of a Day

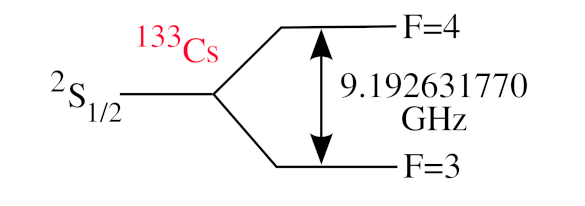

July 24, 2023 Businesses advertise their availability as 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and 365 days a year (24/7/365), I always thought it strange that they all decided to take leap year day as a holiday. Since the length of time between one vernal equinox or autumnal equinox to another is 365 days, 5 hours, 48 minutes, and 46 seconds (365.2422 days), we need to add a day every four years to more closely track the seasons over time in our Gregorian calendar. This 0.25 day correction is a little too much, so years exactly divisible by 100 are leap years only if they are exactly divisible by 400; so, the year 2000 was a leap year. The passage of time is presently measured by atomic clocks with the precision of more than one part in 1014, for an precision of about one second in a billion years. I wrote about a ytterbium atomic clock in an earlier article (Ytterbium Atomic Clock, March 16, 2012). The second has been defined since 1967 as 9,192,631,770 ticks of the unperturbed ground state hyperfine transition of cesium-133. The frequency of this transition is easily accessed by our present radio frequency technology by which nearly everyone has a gigahertz transmitter and receiver in their 5G cellphones.

The atomic clock electron transition in cesium-133. (Created using Inkscape)

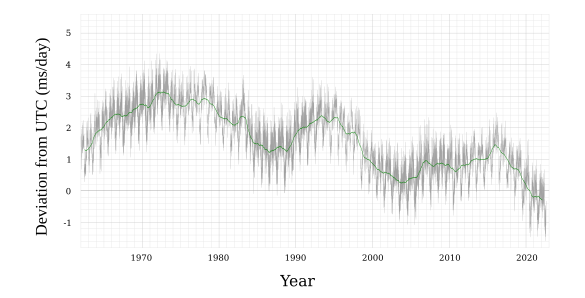

Earth's rotational rate is slightly variable, and it slows enough for a leap second to be added as required. Since the leap second was introduced in 1972, there have been 27 leap seconds added to the Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). Whether a leap second is added at year's end, or not, is decided about six months prior by the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS). Leap seconds can't be planned farther in advance than that, since the Earth's short term rotation rate is unpredictable. Why would Earth's rotational rate change at all? The main factor is the tidal friction of the oceans caused by the Sun and Moon. This lengthens the day by 2.3 milliseconds per century. Earth's core being liquid with variable convective flows causes short-term variation. Large crustal events change the distribution of mass, and thereby Earth's moment of inertia. The Indian Ocean earthquake of 2004 apparently shortened the day by 2.68 microseconds. A mathematical model of the length of the solar day was created in 2004 based on eclipse records from 700 BC -1623 AD, other telescopic observations from 1623-1967, and atomic clocks from 1968-1990.[1] The model revealed a long-term increase of the mean solar day by 1.70 ms per century and a periodic shift of about 4 ms in amplitude with a period of about 1,500 years.[1]

Deviation of day length from the day derived from the SI second for the period 1962-2022. The annual variation is apparent, as well as the unpredictable short-term and long-term variations in these data from the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IER). (Modified Wikimedia Commons image. Click for larger image.)

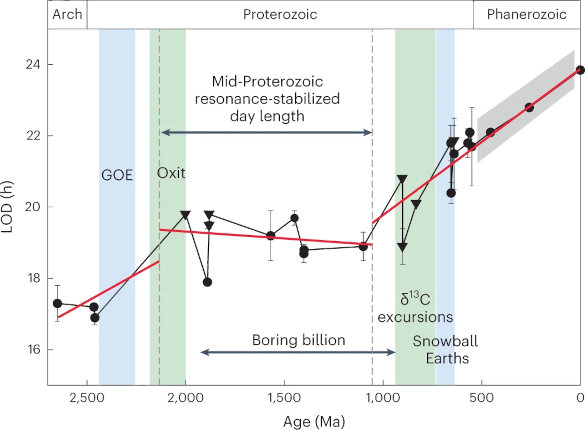

Crossing time zones and the changes back and forth between standard time and daylight saving time have always been an annoyance. However, the advent of the Internet created problems that focused on the seconds level of time. Such problems include accurate timestamping of communications and process control systems, especially interactions between computers that adjust for leap seconds, and those that don't. On my Linux desktop computer, leap seconds are handled by repeating 23:59:59. That's because the useful timestamp, Unix time, wants a day to be exactly 86,400 seconds. There's a movement afoot to abandon the leap second as a simplification (and let our progeny deal with any consequences, as for the year 2000 problem). The length of a day is presently increasing. Does this mean that Earth's day was much shorter in the distant past? An international team of geoscientists from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Beijing, China), the University of Tübingen (Tübingen, Germany), and Curtin University (Perth, Australia) found that the day length in the Mid-Proterozoic was just 19 hours.[2-3] More interestingly, this 19 hour day persisted for a billion years.[2-3] This persistence of day length at 19 hours coincides with a period of relatively limited biological evolution that's known as the boring billion.[2-3] It's generally accepted that Earth's rotation was more rapid in the past as it is now, leading to a shorter day.[3] That's because the Moon's orbit was closer to Earth. Since the Earth rotates faster than the orbital angular velocity of the Moon, the oceanic tidal bulge of Earth is pushed ahead of the Moon. This exerts a torque on the Moon and boosts the Moon to a farther orbit.[2] However, by angular momentum conservation, Earth's rotation slowed as the Moon's orbital radius increased.[3] A geological record of day length is preserved in some sedimentary rocks created by fine-scale layering in tidal mudflats.[3] The number of layers relates to tidal fluctuations, but such an analysis is difficult.[3] A better approach, called cyclostratigraphy, is to examine a different type of sedimentary layering affected by astronomical events called Milankovitch cycles reflecting climate variations caused by changes in Earth's orbit and rotation.[3] Says Uwe Kirscher, a study author and a research fellow in the School of Earth and Planetary Sciences of Curtin University,

"Two Milankovitch cycles, axial precession of the Earth and obliquity, are related to the wobble and tilt of Earth's rotation axis in space. The faster rotation of early Earth can therefore be detected in shorter precession and obliquity cycles in the past."[3]

Milankovitch cycles captured in 600-million-year-old sedimentary rock.

Analysis of such sediments allows an estimate of the length of day in Earth's distant past.

(Chinese Academy of Sciences image by Ross Mitchell. Click for larger image.)

Kirscher and fellow author, Ross Mitchell, an associate professor in the Institute of Geology and Geophysics Chinese Academy of Sciences (IGGCAS), were encouraged to do their study after a dramatic increase in Milankovitch geological data in the past seven years, especially for the Precambrian, a geological period extending from 4.6 billion to about 538.8 million years ago.[3] Such data allow length of day estimation at a time when other biological means, such as tree rings and coral growth bands, are not possible.[2] Their statistical analysis of the Precambrian data for the length of day showed that it stalled at about 19 hours for about 1 billion years during in the middle of the Proterozoic.[2] The Proterozoic is the geological eon extending from 2500 to 538.8 million years ago.[2] It's theorized that atmospheric thermal tides from solar energy, which cause an accelerative torque, were balanced by the decelerative torque of lunar oceanic tides, and this stabilized Earth's rotation.[2] Says Kirscher,

"Because of this, if in the past these two opposite forces were to have become been equal to each other, such a tidal resonance would have caused Earth's day length to stop changing and to have remained constant for some time."[3]This stalling of day length ends with a large rise in atmospheric oxygen. This indicates that longer days were needed for photosynthetic bacteria to generate more oxygen.[3]

Summary of the length of day data from Extended Data Table 1 of ref. 2, including error bars when possible.[4] (Fig. 2 of ref. 2, released under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.[2] Click for larger image.)

References:

- L. V. Morrison and F. R. Stephenson, "Historical Values of the Earth's Clock Error Δ and the Calculation of Eclipses," Journal for the History of Astronomy, vol. 35, part 3, no. 120 (2004), pp. 327-336, https://doi.org/10.1177/002182860403500. The article is unfortunately paywalled, but images of all pages are available at the SAO/NASA Astrophysics Data System (ADS).

- Ross N. Mitchell and Uwe Kirscher, "Mid-Proterozoic day length stalled by tidal resonance," Nature Geoscience, June 12, 2023, DOI: 10.1038/s41561-023-01202-6. This is an open access article with a PDF file at the same URL

- 19-hour days for a billion years of Earth's history: Study, Chinese Academy of Sciences Press Release, June 12, 2023.

- Supplementary materials for ref. 2.