Medieval Volcanism

June 5, 2023 One principal lesson that every scientist learns is to keep detailed notes of his experiments and observations. For most of the 20th century, this involved actually handwriting the notes and pasting graphs into a bound volume. Today, computers serve as the data collection medium, rather than paper, and this makes addition of graphics and photographs much easier. Proper electronic lab notebooks include immutable timestamps that show the time of creation of the notebook entry for patent and priority purposes. This careful documentation aspect of the scientific method is just a few centuries old. Before that time, people may have noticed things they didn't understand, but they wrote them down as portents from God, or for other reasons. Scientists have developed ways of combining these abstruse mentions with other data to reconstruct the historical record of natural phenomenon.

Bad omen in 1556.

A comet appeared on May 5, 1556, and it was followed by an earthquake at Constantinople (present day Istanbul) on May 10, 1556.

The dome of Hagia Sophia was heavily damaged, as were other buildings, and there were many fatalities.

(Colored woodcut by Herman Gall (1554–1580), via Wikimedia Commons. Click for larger image.)

Volcanic eruption is one type of natural cataclysm that can have a global affect. The 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens in Washington State emitted a 1.1 km3 (0.26 cubic mile) cloud of volcanic ash that spread across the contiguous United States in 3 days, and circled the Earth in 15 days. The volcanic ash creates red sunrises and sunsets, there is also emission of carbon dioxide, as well as a release of sulfur dioxide that creates sulphate aerosols that reflect solar radiation to cause a transient global cooling.[1] The 10 million tons of carbon dioxide released by the Mount St. Helens eruption pales in comparison with the 50 million tons of carbon dioxide and 20 million tons of sulfur dioxide released by the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines.[1] This eruption caused a maximal cooling of about 1.3 degrees F.[1] It's estimated that global sulfur dioxide emission from volcanoes is about 23 ± 2 million tons a year.[2] The 1883 eruption of the Krakatoa volcano killed more than 36,000 people, and it was so intense as to have been heard up to 3,000 miles away. Its pressure wave was intense enough to circle the globe three and a half times, its ejecta caused the average global temperature to fall by more than a degree Celsius (°C) in the subsequent year, and cause disruption of weather patterns for five years.

The "afterglow" of the 1883 Krakatoa eruption, as published by the Royal Society of Great Britain Krakatoa Committee. (Illustration from "The eruption of Krakatoa, and subsequent phenomena," 1888, George James Symonds, Ed., Item 71-1250 from the Houghton Library, Harvard University, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Since these three volcanic events occurred in recent history, they were carefully documented. However, a particular volcanic eruption in ancient history was so intense as to have given rise to the Atlantis myth, a topic that I wrote about in a very early article (Science and the Atlantis Myth, May 18, 2012). Atlantis was a supposedly advanced culture that was wiped off the face of the Earth by some cataclysm. The Minoan civilization, discovered by archaeologists at the start of the last century, has been proposed as a remnant colony of Atlantis. The Atlantis myth started with an account by Plato in his Timaeus. He described the demise of Atlantis at about 9,600 BC, about seven millennia before his time. As Plato wrote, Atlantis sank into the ocean "in a single day and night" after a failed invasion of Athens.[3]

Portion of Plato's Timaeus recalling the demise of Atlantis. The English translation reads, "..At a later time there occurred portentous earthquakes and floods, and one grievous day and night befell them, when the whole body of your warriors was swallowed up by the earth, and the island of Atlantis in like manner was swallowed up by the sea and vanished; wherefore also the ocean at that spot has now become impassable and unsearchable, being blocked up by the shoal mud which the island created as it settled down." (Via Project Perseus).[3]

The island of Santorini, known in antiquity as Thera, was nearly destroyed by a violent volcanic eruption, thought to be among the most powerful in civilized times, at about 1650 BC, and the idea that Atlantis was Thera was first proposed in 1960. This is much nearer in time to Plato than Plato's 9,600 BC event, but it would be unlikely that an event of 9,600 BC would still be within human memory. However, an event about a millennium before may have, giving credence to the identification of Thera with Atlantis. Plato's description of a catastrophe within a single day and night is consistent with a volcanic eruption and ensuing tsunami, as found in the geologic record. As I recalled in an earlier article (The Year 536, March 18, 2019), extreme weather in the 6th century, starting around the years 535-536, was chronicled by various historical sources. Byzantine historian, Procopius (c.500 - c.554), wrote in his History of the Wars, Book IV, Chapter XIV,

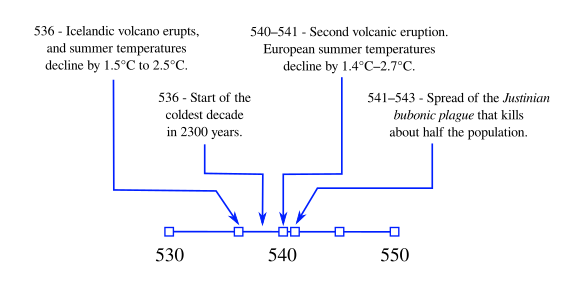

For the Sun gave forth its light without brightness, like the Moon, during this whole year, and it seemed exceedingly like the Sun in eclipse, for the beams it shed were not clear nor such as it is accustomed to shed.The cause was unknown at the time, but scientific study has now demonstrated that it had a volcanic origin.[4-6] Ice core analysis showed that a 536 volcanic eruption was quickly followed by two others, in 540 and 547.[4-6] Europe, the Middle East, and parts of Asia were blanketed by a mysterious fog for 18 months, and tree ring studies, a traditional climate-tracking method, revealed that the years around 540 were unusually cold.[8-9] summer temperatures in 536 were 1.5°C to 2.5°C lower, and this was the start of the coldest decade in the past 2300 years.[5-6]

Timeline of events from 530-550. The eruption of an Icelandic volcano in 536 led to decreased insolation, cooler weather, crop failure, and a plague. (Created using Inkscape from data in refs. 4-6.[4-6] Click for larger image.)

A recent research paper in Nature reports on the use of data mining techniques on High Medieval Period (1100-1300) manuscripts for mentions of the appearance of the Moon during total lunar eclipses to disclose the incidence of volcanic eruptions.[7-9] In a total lunar eclipse, the Moon is fully in Earth's shadow, and such eclipses occur about every six months, during the full moon, when the orbital plane of the Moon is closest to the plane of the Earth's orbit. This occurs at syzygy, when the Sun, Earth, and Moon are exactly, or very closely, aligned during nights of a full moon.

Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543) published his De revolutionibus orbium coelestium and its heliocentric theory in 1543.

However, lunar eclipses could be explained using the geocentric model of Ptolemy, as shown in this diagram from De sphaera mundi, published circa 1230, by Johannes de Sacrobosco (c.1195-c.1256)

Libraries, University of Missouri

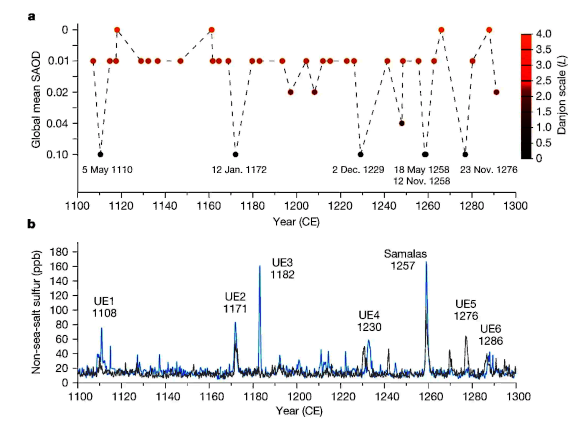

This study was done by a huge international team of scientists and scholars from the University of Geneva (Geneva, Switzerland), the Université Clermont Auvergne (Clermont-Ferrand, France), the University of Cambridge (Cambridge, United Kingdom), the Université Paris (Thiais, France), the Sorbonne Université (Paris, France), Trinity College Dublin (Dublin, Ireland), the University of Bern (Bern, Switzerland), the University of Saskatchewan (Saskatchewan, Canada), and the University of Washington (Seattle, Washington).[7] Large volcanic eruptions occurring close together during the High Medieval Period (1100-1300) have been proposed as the cause of a cold period in Europe known as the Little Ice Age that cased an advance of European glaciers.[7,9] It's known that strong tropical eruptions will induce about one degree Celsius of global cooling that lasts a few years.[9] People living during that period could not have imagined that the extreme cold and unusual lunar eclipses were caused by volcanoes, since the eruptions were, except in one case, undocumented.[9] While data from such things as ice core sampling show the chronology of volcanic eruptions, there's still the problem of determining whether the eruptions pushed volcanic sulfate aerosol into the troposphere or the stratosphere.[7] The Moon will be dark at a total lunar eclipse if there are high concentrations of volcanic aerosols in the stratosphere, while a reddish Moon is an indicator that they are scarce.[7] The research team spent nearly five years examining hundreds of annals and chronicles from Europe and the Middle East from the twelfth century and thirteenth century in a search for references to the coloration of total lunar eclipses.[7,9] An additional source was data recorded by astronomers in China and Korea.[7] European sources were generally from the annals and chronicles from towns and monasteries.[7] Arabic mentions of lunar eclipse observations are noted in universal chronicles.[7] Monks were inspired to note the coloration, since the Book of Revelation indicates that a blood-red Moon is a sign of the end times.[9] European chroniclers documented 51 of the 64 total lunar eclipses that occurred in Europe between 1100 and 1300; and, in five of these, they reported that the Moon was exceptionally dark.[9] A Japanese scribe wrote of an unprecedented dark eclipse on December 2, 1229, as follows:

"the old folk had never seen it like this time, with the location of the disk of the Moon not visible, just as if it had disappeared during the eclipse... It was truly something to fear."[9]Data for a total of 187 lunar eclipses between 1100 and 1300 were discovered.[8] Seven High Medieval Period volcanic eruptions each generated an estimated stratospheric sulfur injection exceeding 10 million metric tons, marking them among the top sixteen events of the past 2,500 years.[7] There was a cluster of events around 1108-1110, including the colossal Samalas eruption of 1257, and these have been proposed as a contributors to the onset of the Little Ice Age.[7,8] The estimated years for these eruptions were 1108, 1171, 1182, 1230, 1257 (Samalas), 1276, and 1286.[7] The Samalas eruption rivals the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora that resulted in the year without a summer of 1816.

Coincidence between total lunar eclipses and medieval volcanism. Total lunar eclipse descriptions were collected from European, Middle Eastern and East Asian historical sources from 1100 to 1300. (Fig. 2 of ref. 7, released under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.[7] Click for larger image.)

References:

- Volcanoes Can Affect Climate, Volcano Hazards Program, U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey.

- XXS. A. Carn, V. E. Fioletov, C. A. McLinden, C. Li, and N. A. Krotkov, "A decade of global volcanic SO2 emissions measured from space," Scientific Reports, vol. 7 (March 9, 2017), Article no. 4095, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44095. This is an open access paper with a PDF file here.

- Verses 25c-25d of Plato's Timaeus, from Plato in Twelve Volumes, vol. 9, W.R.M. Lamb, Translator, (Cambridge, Harvard University Press), 1925, via Project Perseus; Greek text from Platonis Opera, John Burnet, Editor, Oxford University Press, 1903.

- Ann Gibbons, "Eruption made 536 'the worst year to be alive'," Science, vol. 362, no. 6416 (November 16, 2018), pp. 733-734, DOI: 10.1126/science.362.6416.733.

- Ann Gibbons, "Why 536 was 'the worst year to be alive'," Science (November 15, 2018), doi:10.1126/science.aaw0632.

- Ultra-Precise Ice Core Sampling and the Explosive Cause of the Dark Ages – Mayewski & Kurbatov, University of Maine Climate Change News, December 18, 2018.

- Sébastien Guillet, Christophe Corona, Clive Oppenheimer, Franck Lavigne, Myriam Khodri, Francis Ludlow, Michael Sigl, Matthew Toohey, Paul S. Atkins, Zhen Yang, Tomoko Muranaka, Nobuko Horikawa, and Markus Stoffel, "Lunar eclipses illuminate timing and climate impact of medieval volcanism," Nature, vol. 616 (April 5, 2023), pp. 90-95, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-05751-z. This is an open access paper with a PDF file here.

- Andrea Seim, Eduardo Zorita, and Anne Lawrence-Mathers, "The medieval Moon unveils volcanic secrets," Nature, vol. 616 (April 5, 2023), pp. 38-40, doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-00850-3. This is an open access paper with a PDF file here.

- The unexpected contribution of medieval monks to volcanology, Université de Genève Press Release, April 5, 2023.