Gordon Moore (1929-2023)

April 10, 2023 As a member of the baby boomer generation, my university education coincided with the replacement of slide rules by mainframe computers for scientific and engineering calculations. I was interesting in computing, but I was dissuaded from ever taking a computer programming course as a result of the computer paradigm in those early days. students would key their FORTRAN programs onto punch cards, and pass huge boxes of these to the High Priests of Computing, who would eventually produce a print-out of their results or syntax errors. If your program had errors, you would need to punch corrected cards and go through the lengthy process once again. This wasn't the computer paradigm I had grown to anticipate from science fiction books and films.

An 80 column punch card. Such punch cards were once so common that artisans would make Christmas wreaths and Easter flowers from them. (Enhanced (Wikimedia Commons image. Click for larger image.)

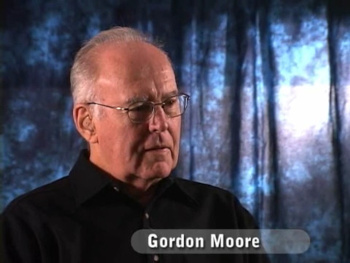

Eventually, I had access to time-sharing terminals at which I taught myself FORTRAN and APL, and I learned enough computer programming to publish a simulation program for magnetic bubbles in 1980.[1] However, my true goal was to have a home computer, and I built one after another of these from the late 1970s onward. One of the earliest of these computers used an Intel 8080 microprocessor that ran machine language programs stored on audio cassette tape entered with an octal keypad and a monitor program I had burned into an ultraviolet-erasable programmable memory chip (PROM). Gordon Moore, a co-founder of Intel Corporation, died on March 24, 2023, at the age of 94.[2-5] He is survived by Betty, his wife of 50 years, sons Kenneth and Steven, and four grandchildren.[3,5]

Gordon Moore, January 25, 2008.

(Still image from a YouTube video, "Oral History of Gordon Moore," at the Computer History Museum.)

Although you would expect a computer hardware pioneer to be a physicist or an electrical engineer (The three Nobel Laureates for the invention of the transistor, William Shockley (1910-1989), John Bardeen (1908-1991), and Walter Brattain (1902-1987), were all physicists), Gordon Moore was a physical chemist. He enjoyed working with chemistry sets as a child, and this likely influenced his career path.[3] Moore received his PhD in chemistry in 1954 from the California Institute of Technology, and from 1953 to 1956, he was a postdoctoral research associate at the Applied Physics Laboratory. Moore joined Shockley's eponymous Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory, a division of the successful scientific instrument manufacturer, Beckman Instruments. Unfortunately, Shockley's authoritarian management style, combined with a lack of technical focus for the laboratory, caused his talented employees, including Moore, to leave to found a new semiconductor device startup, Fairchild Semiconductor Corporation, on September 18, 1957. Shockley called this team, the traitorous eight. This started a Silicon Valley culture in which technologists would start a competitive company when they thought their present employer was making bad decisions.[3] The eight started Fairchild with $500,000 of their own money and venture capitalist backing.[3]

Historical marker for the invention of the integrated circuit at Fairchild.

Fairchild's Robert Noyce (1927-1990) is credited with the invention in 1959 of the first monolithic integrated circuit chip,[7] but he relied on a technology base from many people, especially the Planar processing technology of his colleague, Jean Hoerni (1924-1997), another of the traitorous eight.

Jack Kilby (1923-2005) of Texas Instruments invented a less refined integrated circuit at the same time,[8] and he was awarded the 2000 Nobel Prize in Physics, "...for his part in the invention of the integrated circuit". Noyce would likely have shared the prize, but the Nobel Prize is never awarded posthumously.

(Wikimedia Commons image by Richard F. Lyon. Click for larger image.)

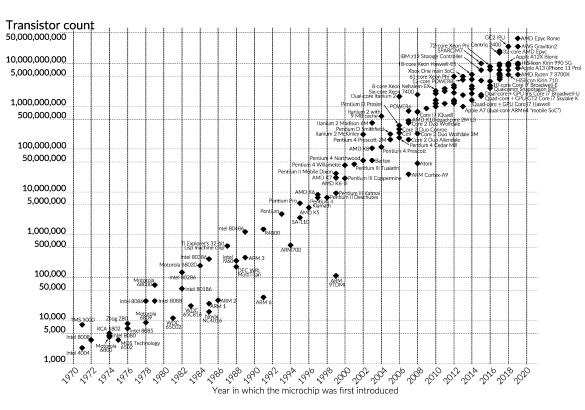

In mid-1958, Moore and Robert Noyce (1927-1990) left Fairchild after nine years and founded NM Electronics, with a name change to Intel a year later. Moore was Intel's executive vice president until 1975, and president until 1979, when he became chairman of the board and chief executive officer.[3,5] In 1987, Moore relinquished his CEO position and continued as chairman.[3,5] Moore became chairman emeritus in 1997, finally stepping down in 2006.[3,5] Moore is best known for his eponymous Moore's Law, which predicted an exponential growth in the number of transistors in an integrated circuit. His prediction was published in 1965 while he was still at Fairchild in the trade journal, Electronics.[2,6] His initial prediction was that the number of transistors would double every year, but he revised this to every two years in 1975, and he thought that his law would hold for a decade thereafter. However, Moore's law became a technology roadmap to this day; that is, there must be a doubling every two years.[2]

Moore's Law, 1970-2020. (Modified Wikimedia Commons image by Max Roser and Hannah Ritchie of ourworldindata.org. Click for larger image.)

Late in life, buoyed by the fortune he had made with Intel, Moore started the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation with his wife.[2] The foundation worked to protect biodiversity, improve engineering education, and fund astronomy research.[6] His interest in astronomy was personal, since he enjoyed using an eight inch Meade Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope he received from his family as a birthday gift.[6] During the dot-com bubble, Moore's personal wealth rose to a peak of $24 billion.[6] His original endowment to the foundation was worth $11 billion, but it dropped quickly to $5 billion.[6] The Foundation donates $300 million annually, and it's donated more than $5.1 billion at this time.[3,6] Early in its history, the Moore Foundation donated $300 million to his alma mater, the California Institute of Technology.[6] Moore personally donated another $300 million to CalTech.[6] Moore was a member of the National Academy of Engineering, and a Fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE).[5] He was awarded the IEEE Medal of Honor in 2008 "for pioneering technical roles in integrated-circuit processing, and leadership in the development of MOS memory, the microprocessor computer, and the semiconductor industry".[4,6] He received the National Medal of Technology in 1990, and the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian US honor, in 2002.[2-4,6] Moore was interviewed at the Computer History Museum (Mountain View, California) on January 25, 2008.[9-10] Some of his remarks that I found particularly interesting appear below.

• "I had a couple of teachers in high school I was quite fond of who I thought were very good... particularly my math teacher, who I thought gave me a good start there."

• "I was a physical chemist by training. Shockley knew chemists did some good things for him at Bell Labs, so he needed one out here."

• "In my education and subsequent work, I'd done a lot of technical glass blowing, making the old gas jungles that let you manipulate gases and purify materials."

• "We had one engineer who sealed some silicon and some arsenic into a quartz capsule and shoved it into the furnace. He forget to look up the vapor pressure of arsenic and the tube exploded and arsenic vapors went all around the laboratory."

• "Well, I don't think we moved the state of the art ahead very much (at Shockley Semiconductor). Looking back at it, it was really a dirty facility.... The net result was we had a very difficult time making devices with good electrical characteristics. We learned a lot of things not to do, and when we went off and started Fairchild, we could use that knowledge of what not to do to start off in a new direction with a much better idea of where we wanted to go eventually."

• "The silicon itself... initially we thought we had to grow our own crystals (at Fairchild)... as soon as we could buy them on the outside, we abandoned that particular part of the business."

• "So, when we set up Intel, we decided we'd do nothing on equipment internally, we'd work with the vendors, and even if this resulted in technology we developed getting transferred to the rest of the industry, it would be the most effective way for us to continue to grow."

• "We ended up buying Japanese (photolithography) equipment because it was the best available, and there wasn't really an alternative source for that. And I guess that's still the case now with lithography equipment."

• "I remember giving a talk at a SEMI meeting once... that the bus leaves on a particular sort of technology at a particular time, and if they're not in that first bunch of equipment, they lose that whole generation. They can come in six months later with a better machine, but it wouldn't be used by Intel. The processor had already been developed with the equipment that was there."

• "I continually am amazed at how big the wafers have gotten. I don't believe that I was convinced we'd go beyond about 6 inches for a long time."

• "I know one case for example kind of etched in my mind, where Intel's most profitable product price fell 90 percent in nine months. While the industry's good at decreasing cost, it can't follow that kind of a curve. So, this caused fairly abrupt dislocations, but that price never comes back up."

• "And amazingly enough, that ten doublings in complexity that I predicted turned out to be nine doublings, actually, pretty close, much closer than it had any basis to be. But it got the name Moore's Law... In 1975, I redid it, changed the slope, and again expected a decade or so to be all we were looking at. And in fact, we stayed on that amazingly closely ever since. In fact, if anything, we've done better than my revised prediction in '75... And we're getting pretty close to molecular dimensions in the devices we're making now, and that's going to become a fundamental limit in how we can continue to shrink things."

• "The first microprocessors after the calculator went to a variety of funny applications. The one that stands out in my memory was somebody automated a hen house... Now, I don't know what you do when you automate a hen house, but I remember that that was a peculiar application."

• "The actual idea of an MOS transistor was patented in the mid-'20s. You just couldn't make it practically at that time."

References:

- D.M. Gualtieri, "Computer Program Description: SPECS," I.E.E.E. Trans. Magnetics, vol. MAG-16, no, 6 (November, 1980), pp. 1440-1441, DOI: 10.1109/TMAG.1980.1060889.

- Gordon Moore, Intel co-founder and creator of Moore's Law, dies aged 94, BBC News, March 25, 2023.

- Gordon Moore, Intel co-founder and philanthropist, dies at 94, The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 25, 2023.

- Remembering Gordon Moore, IEEE-USA, March 27, 2023.

- Gordon Moore, Intel Co-Founder, Dies at 94, Intel Corporation Press Release, March 24, 2023.

- Tekla S. Perry, "From the 2008 Archives: Gordon Moore's Next Act," IEEE Spectrum, May 1, 2008.

- Robert N Noyce, "Semiconductor device-and-lead structure," US Patent No. 2,981,877, April 25, 1961 (via Google Patents).

- Jack S Kilby, "Miniaturized electronic circuits," US Patent No. 3,138,743, June 23, 1964 (via Google Patents).

- Oral History of Gordon Moore, Computer History Museum YouTube Video, March 24, 2008.

- Transcript of ref. 9, Computer History Museum, Catalog Number 102658233, January 25, 2008, 13 pp.