Georges Lemaître

May 22, 2023 Observational science has been with us since the early Greek philosophers, but experimental science began with Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) and such novel experiments as his using balls rolling down inclined planes to measure gravitational acceleration. The Roman Catholic Church in Galileo's time had for three centuries embraced the teachings of Aristotle (384-322 BC), and this caused it to reject many of Galileo's beliefs and discoveries. It seems strange that the pagan, Aristotle, would have such an influence on the Church. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), a Dominican, friar and priest, and subsequent saint (1323), was responsible for Aristotle's influence on the church. Thomas had great esteem for Aristotle, and his efforts to harmonize Aristotle's ideas with Christian theology became a movement called Scholasticism. As a consequence, all of Aristotle's ideas were embraced by the Church.

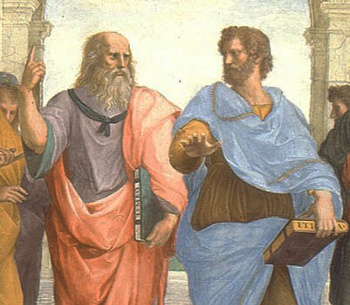

Plato (c.428 BC-c.348 BC), left, and Aristotle (384 BC-322 BC), from Raphael's The School of Athens.

Plato is holding his Timaeus, and Aristotle is holding his Nicomachean Ethics.

Aristotle was a student of Plato.

(Portion of a Wikimedia Commons image.)

Aristotle believed in a geocentric universe with Earth at its center. As a consequence, the heliocentric universe of Nicholas Copernicus (1473-1543) was anathema. In 1616, the Church banned Copernicus' 1543 book, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres). Galileo ran afoul of the Church with publication of his 1632 book, Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems that gave credence to heliocentrism.[1-2] In 1633, this book was placed on the Index of Forbidden Books, and it wasn't removed until 1835. Because of ill health and advanced age, Galileo was sentenced to villa arrest, and he died in 1642.[1] Although not a reason for his imprisonment, Galileo's telescopic observations of the Moon that revealed imperfections in the heavens above were likewise contrary to Aristotle's ideas. Centuries later, in 1992, Pope John Paul II declared the validity of heliocentrism, and he subsequently apologized for the Church's treatment of Galileo. While the Church had a problem with such interpretations of astronomical observations, it supported such observations for the reason that the dates of movable feasts, such as Easter, are determined by the phase of the Moon. The Vatican Observatory (Specola Vaticana), the latest in a long line of Church observatories, was established at the Vatican in 1891, and it was among the most notable observatories of the world. After forty years, it was moved as a consequence of the increasing light pollution in Rome to Castel Gandolfo, a town 16 miles (25 kilometers) southeast of Rome. Castel Gandolfo began to have similar problems; and, in 1961, the Vatican Observatory Research Group (VORG) was established at Steward Observatory of the University of Arizona (Tucson, Arizona). Despite all the motion in the Solar System, the stars of the night sky were presumed to just sit where they were created, giving rise to the terminology, fixed stars. In 1718, however, English astronomer, Edmond Halley (1656-1741), discovered the proper motion of stars when he noticed that Aldebaran, Arcturus, and Sirius were quite noticeably away from the positions measured by the ancient Greek astronomer, Hipparchus (c.190-c.120 BC). While proper motion did not cause too much excitement in astronomical circles, another motion did. That was the expansion of the universe, discovered by American astronomer, Edwin Hubble (1889-1953). This expansion is quantified in the eponymous Hubble's law, which expresses the rate of this expansion, the Hubble constant. While Hubble is renowned for discovery of universal expansion, Belgian priest and astronomer, Georges Lemaître (1894-1966), discovered Hubble's law before Hubble.[3] Unfortunately, Lemaître's 1927 paper on this idea was published in French in a lesser known journal where it was ignored.[3] As I wrote in a previous article (Hubble and His Law, July 31, 2013), noted astronomer, Virginia Trimble (b. 1943), listed quite a few precursors other than Lemaître to Hubble's law in an arXiv article.[4]

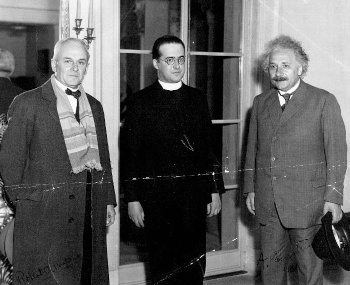

Georges Lemaître (1894-1966), center, with Robert A. Millikan (1868-1953), left, and Albert Einstein (1879-1955), right.

Einstein and Millikin were both Nobel Physics Laureates. Millikan received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1923 for his 1909 oil drop experiment in which he measured the charge of the electron, which is the elementary electric charge.

(Wikimedia Commons image. Click for larger image.)

If the universe is expanding, there's the simple idea that we can extrapolate backwards in time to a point of creation. Lemaître was the first to propose the notion that the universe started in a Big Bang in a letter to Nature on May 9, 1931.[6] The letter speculated that the entire mass of the universe was initially contained in an "atom" of chaotic material.[5] As Lemaître wrote,

"We could conceive the beginning of the universe in the form of a unique atom, the atomic weight of which is the total mass of the universe ... [and which] would divide in smaller and smaller atoms by a kind of super-radioactive process."[5]As noted by Danish science historian, Helge Kragh (b. 1944), Lemaître's atom was matter that was undifferentiated and devoid of physical properties.[5] Kragh also notes that Lemaître, who was writing for a scientific audience, makes it clear that his theory was about the origin of the universe, and not its creation. As Lemaître wrote, "The question if it was really a beginning or rather a creation, something starting from nothing, is a philosophical question which cannot be settled by physical or astronomical considerations."[5] There's renewed interest in Lemaître after the discovery of a supposedly lost 1964 video interview with him by the Vlaamse Radio- en Televisieomroeporganisatie (VRT), the national public-service broadcaster for the Flemish Community of Belgium.[7-9] An arXiv posting at the end of last year provides an English translation of the interview.[7]

Georges Lemaître during the 1964 video interview with him by the Vlaamse Radio- en Televisieomroeporganisatie (VRT), the national public-service broadcaster for the Flemish Community of Belgium.

(Still image from the video of ref. 9. Click for larger image.)

Although a three minute excerpt existed, the entire 19 minute, 47 second, interview, broadcast on Friday, February 14, 1964, was thought to have been lost.[7] However, it was recently found to have been mislabeled and misclassified.[7] As the authors state in their arXiv paper, they believe that this video, done two years before his death, is the only video interview of Georges Lemaître in existence.[7] Unfortunately, brief portions of the audio are unintelligible. Since our understanding of cosmogony has changed so much in the intervening years, the transcript is difficult to understand. However, several of Lemaître's responses are memorable, such as this:

"When one poses the problem of the beginning of the world, one is almost always faced with a rather essential difficulty: to ask oneself, why did it begin at that moment? Why didn't it start a little earlier? And in a certain sense, why wouldn't it have started a little earlier? So it seems that any theory that involves a beginning must be unnatural."

References:

- Henry Ansgar Kelly, "Galileo's Non-Trial (1616), Pre-Trial (1632–1633), and Trial (May 10, 1633): A Review of Procedure, Featuring Routine Violations of the Forum of Conscience," Church History, vol. 85, no. 4 (December, 2016), pp. 724-761, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0009640716001190.

- Jessica Wolf, "The truth about Galileo and his conflict with the Catholic Church," UCLA Press Release, December 22, 2016 .

- Jean-Pierre Luminet, "Editorial note to "A Homogeneous Universe of Constant Mass and Increasing Radius accounting for the Radial Velocity of Extra--Galactic Nebulae" by Georges Lemaître (1927)," arXiv, May 28, 2013.

- Virginia Trimble, "Anybody but Hubble!" arXiv, July 8, 2013.

- Helge Kragh, "Cosmology and the Origin of the Universe: Historical and Conceptual Perspectives," arXiv, June 2, 2017.

- G. Lemaîum;tre, "The beginning of the world from the point of view of quantum theory," Nature, vol. 127 (May 9, 1931), p. 706, https://doi.org/10.1038/127706b0.

- Satya Gontcho A Gontcho, Jean-Baptiste Kikwaya Eluo, and Paul Gabor, "Resurfaced 1964 VRT video interview of Georges Lemaître," arXiv, January 19, 2023, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2301.07198.

- Katherine Wright, "A Rare Glimpse into a Bygone Era," Physics, vol. 16, no. 67 (April 21, 2023).

- Eric Steffens, "Conservé. A présent, l'intégralité de l'interview d'une durée de 20 minutes a été retrouvée," VRT, December 31, 2022.