Edgar Allan Poe and Science

February 21, 2022 The starving young author idiom has historical roots in the life of American author, Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849), who was the first famous American writer to earn a meager living exclusively through writing. Most people will associate Poe solely with his many horror stories depicted as films and on television, but his interests extended beyond this. Poe also wrote some of the first science fiction. One such story, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1838),[1] was the inspiration for an 1897 sequel by Jules Verne (1828-1905) entitled, Le Sphinx des glaces. As I wrote in an earlier article (Future Water Scarcity, March 28, 2016) concerning a similar Antarctic theme in The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, a 1798 poem by Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834), Antarctica in those times was a place so strange that it might as well have been the Moon.

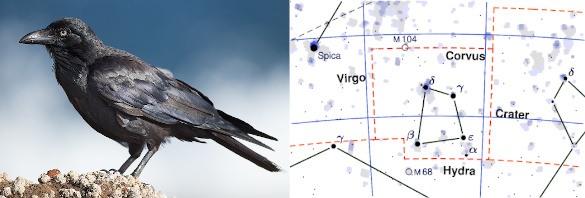

The best known of Poe's poems, The Raven,[2] was published in 1845, and it's notable for its trochaic octameter poetic meter, as illustrated by its first line: [Once up-]1 [on a]2 [mid-night]3 [drear-y]4, [while I]5 [pon-dered]6 [weak and]7 [wear-y]8. The poem features a raven (genus, Corvus) that repeatedly says, "Nevermore." This is not that strange, since ravens are talking birds. For this reason, ravens have culturally represented prophecy. There is also a constellation, Corvus, as shown on the right.

(Left image, Australian Raven (Corvus coronoides) by J.J. Harrison. Right image, Corvus constellation map by Torsten Bronger. Click for larger image.)

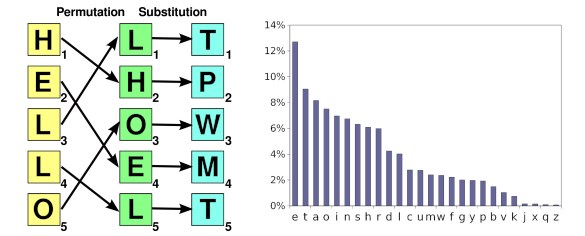

Poe was interested in cryptography, and he placed a notice in a Philadelphia newspaper inviting receipt of ciphers for solution. In July, 1841, he published an essay in Graham's Magazine entitled, "A Few Words on Secret Writing." Simple ciphers, such as substitution ciphers, had much popular interest in those pre-computer days, so Poe subsequently wrote "The Gold-Bug" in 1843, a story that incorporated a cipher as an essential plot device.[3] The cipher was decoded using letter frequency analysis. William F. Friedman (1891-1969), one of America's foremost cryptographers and an important figure in cryptanalysis during World War II, said that his initial interest in cryptography came from reading Poe's "The Gold-Bug" as a child.

Left, the basic cipher operations of permutation and substitution. Permutation and substitution must happen by known rules derived from a passcode in order for the operations to be reversed to decrypt the encrypted message. The simple cipher in Poe's story, "The Gold-Bug," used substitution alone; so, letter frequency analysis (right) allowed an easy decryption.

(Images adapted from my children's book, Secret Codes and Number Games. Click for larger image.)

Poe had a lifelong interest in science, and this scientific side of Poe is explored in a recent biography by John Tresch.[4-7] The practice of science was a nebulous concept during Poe's lifetime, and the word, scientist was only coined by science historian, William Whewell (1794-1866), in 1833.[7] in 1826, Poe entered the University of Virginia, where he proved himself to be a diligent student with considerable literary capability. However, he had problems with drinking and gambling, and also disturbing nightmares. Aside from his studies in history and literature, Poe showed an interest in mathematics, physics and astronomy.[8] In 1830, Poe was admitted to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, where he studied engineering and mathematics.[5,7] When he dropped out of West point, he placed 17th out of his 87 fellow students in mathematics.[7] His next venture was a collaboration on a conchology (the study of sea shells) textbook.[7] This book sold more copies than any other of his books during his lifetime.[7] Starting in 1840, Poe was writing a column on science and art for a men's magazine.[7]

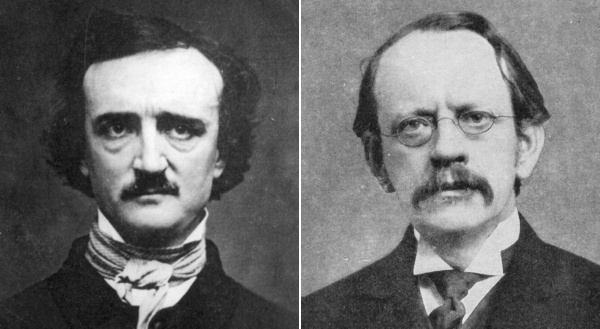

Separated at Birth? As I observed in an article that I had written a decade ago (Bohr model of the Atom, January 3, 2012), there's a strong resemblance between Edgar Allan Poe (left) and J.J. Thompson, who discovered the electron, (right). Image sources for Poe and Thompson via Wikimedia Commons.

Among Poe's first published poems was his Sonnet To Science.[12]

Science! true daughter of Old Time thou art!To ameliorate his often miserable life, Poe would turn to drink, and he would also partake of the opium extract, laudanum. Both of these vices contributed to his significant health problems.[8] In the foreword to a psychoanalytical biography of Poe, Sigmund Freud diagnosed Poe as a pathological case, and this severely damaged Poe's reputation.[10] Poe, however, was typically sober and serious about writing over most of his career.[6] Astronomy was making significant advances in America during Poe's time, and Poe took a special interest in this topic. He even proposed a solution to Olber's paradox that a static and infinite universe should be completely bright.[10] His idea was that the furthest stars were so distant that their light had not yet reached Earth.[8] As a non-scientist, Poe had strange ideas of what constituted science. He respected circus entrepreneur, Phineas T. Barnum, because his "exhibitions were among the most important routes through which working-class audiences learned about natural history and popular mechanics."[6] Poe's final work, the prose poem, Eureka, was concerned with the nature of reality and the universe, and it was dedicated to the German scientist, Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859).[8] The purpose of Eureka was "to speak of the Physical, Metaphysical and Mathematical - of the Material and Spiritual Universe - of its Essence, its Origin, Creation, its Present Condition and its Destiny."[8] It's a strange essay, but it contained some interesting ideas, some of which have probably been overblown in significance in later years, since his approach was more Aristotelian than scientific. One idea in Eureka was that the universe was generated from the explosion of a single primordial particle, the same idea as the Big Bang theory a century later.[8] It also considers the unity of space and time, mass–energy equivalence, and black holes. Eureka also embraced a theory of a cyclic universe, just recently invalidated by detailed measurements of cosmic expansion, and the idea of the multiverse, the existence of multiple universes, each with their own laws of physics.[10] Poe had a strange conception of gravitation, which he thought was an instantaneous effect not constrained by the speed of light.[10] Poe thought that he would be remembered more for his science than for his other writings.[8] Albert Einstein (1879-1955) read Eureka twice, in 1933 and 1940,[10] but he also had a copy of Immanuel Velikovsky's 1950 book, Worlds in Collision on his bedside table at his death.

Who alterest all things with thy peering eyes.

Why preyest thou thus upon the poet's heart,

Vulture, whose wings are dull realities?

How should he love thee? or how deem thee wise,

Who wouldst not leave him in his wandering

To seek for treasure in the jewelled skies,

Albeit he soared with an undaunted wing?

Hast thou not dragged Diana from her car,

And driven the Hamadryad from the wood

To seek a shelter in some happier star?

Hast thou not torn the Naiad from her flood,

The Elfin from the green grass, and from me

The summer dream beneath the tamarind tree?

References:

- Edgar Allan Poe, "The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket," EBook-No. 51060 on Project Gutenberg.

- Edgar Allan Poe, "The Raven (Illustrated)," EBook-No. 45484 on Project Gutenberg.

- Short-Stories (Includes the Gold Bug), Lemuel Arthur Pittenger, Ed., EBook-No. 12732 on Project Gutenberg.

- John Tresch, "The Reason for the Darkness of the Night: Edgar Allan Poe and the Forging of American Science," Farrar, Straus and Giroux (June 15, 2021), 448 pp., ISBN: 978-0374247850 (via Amazon).

- Book Review: The Reason for the Darkness of the Night: Edgar Allan Poe and the Forging of American Science by John Tresch, Goodreads.com.

- Greg Barnhisel, "Review: Edgar Allan Poe loved the science behind the mystery and macabre," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, December 21, 2021.

- Daniel Engber, "Edgar Allan Poe's Other Obsession," The Atlantic, July/August 2021.

- Bibiana García, "The Scientific Side of Edgar Allan Poe," BBVA Open Mind, January 19, 2018.

- The Scientific Side of Edgar Allan Poe, YouTube video by OpenMind.

- René van Slooten, "Edgar Allan Poe--Cosmologist?," Scientific American Guest Blog, February 1, 2017.

- Edgar Allan Poe, "Eureka: A Prose Poem," EBook-No. 32037 on Project Gutenberg.

- Edgar Allan Poe, "Sonnet—To Science, from The Complete Poems and Stories of Edgar Allan Poe (1946), poetryfoundation.org.