X-raying Sealed Letters

April 12, 2021 Superman first appeared in comics in 1938. While he wasn't the first superhero character (the Greek gods might qualify as superheros), he became one of the most popular, and his powers and fanbase increased over the course of many decades. One evidence of popularity is the appearance of "spin-off" characters, such as Superboy, Supergirl, and Krypto the Superdog. One of Superman's powers is his X-ray vision. While this ability to see through walls, etc., has the commonality with X-rays that it's thwarted by a lead shield, it's a strange sort of X-ray vision. The vision is more like terahertz imaging. Unlike conventional X-ray imaging (radiography) in which the imaging is done through transmission of the X-rays through objects, Superman emits X-rays from his eyes to the same effect (I wonder whether he's a licensed X-ray emitter).

Empedocles (c.494-434 BC), as depicted in a 1463 engraving by Neurenberg printmakers Michel Wolgemut and Wilhelm Pleydenwurff.

There's a link between Superman's X-ray vision and the visual perception theory of the fifth century BC Greek philosopher, Empedocles.

(Via Wikimedia Commons.)

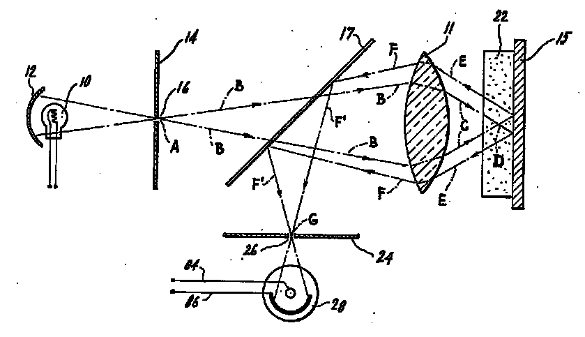

Strange as it sounds, the idea that vision occurs through beams emitted by the eyes was common among some ancient philosophers. This is despite clear evidence, such as the ability to see during the day, not at night, and the existence of shadows, that sunlight is crucial. Plato (c.427-347 BC) and Empedocles (c.494-434 BC) embraced this theory, as did Ptolemy (c.100-170), but it might not surprise us that Euclid (c. 300 BC) did not. In his Optics (Ὀπτικά), Euclid questioned how we can see the distant stars immediately after opening our eyes.[1] It appears that Euclid had the idea that the speed of light was finite. Confocal microscopy is another method used by scientists to image below an object's surface. This technique, patented in 1957 by the ever versatile Marvin Minsky (1927-2016), scans a focused point of light below the surface of a translucent object and detects the reflected light by a similarly focused photodetector. A spatial filter is used to reject light from reflections away from the focused spot. This technique has advanced through the years by the availability of laser light sources and sensitive semiconductor photodetectors, such as avalanche photodiodes, operable at various wavelengths.

Fig. 3 of US Patent no. 3,013,467, "Microscopy apparatus," by Marvin Minsky, December 19, 1961. (Via Google Patents).

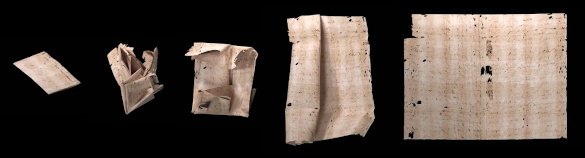

When I was in high school, I read a science fiction story about a man who gained a competitive business advantage by having a device that could copy the fronts and backs of all documents inside closed attache cases. Now, technology like this has appeared half a century later. A recent open access paper in Nature Communications describes the X-ray opening of sealed letters dating from the seventeenth century.[3-5] These letters were a portion of about 2600 "locked" letters that were retained since they were undeliverable. Such locked letters were transformed into their own envelopes by a technique common in the time before the manufacture of envelopes. This research was undertaken by a large international team of scientists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Cambridge, Massachusetts), Adobe Research (San Francisco, California), King's College London (London, UK), Queen Mary University of London (London, UK), Utrecht University (Utrecht, The Netherlands), Leiden University (Leiden, The Netherlands), and Radboud University (Nijmegen, The Netherlands).[3] The research involved a repurposed X-ray scanner used for microtomography in dental research and computational flattening algorithms.[3-5] Such software opening of X-ray microtomographically scanned documents has been done before, but only on scrolls, books, and documents with one or two folds.[3] Letterlocked letters have more intricate folds and tucks, which was a technique to prevent their undetected reading before being opened by the intended recipient.[3-5] Because of the way these letterlocked letters were created, such historical documents could be read only when taken apart.[4] Says study author, Jana Dambrogio, of the Wunsch Conservation Laboratory of the MIT Libraries,

"Letterlocking was an everyday activity for centuries, across cultures, borders, and social classes... It plays an integral role in the history of secrecy systems as the missing link between physical communications security techniques from the ancient world and modern digital cryptography. This research takes us right into the heart of a locked letter."[5]

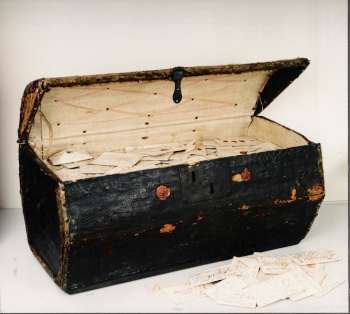

The Brienne Trunk, a cache of seventeenth century letters created by postmaster and postmistress, Simon and Marie de Brienne.

This collection is now at the Dutch postal museum in The Hague.

(Queen Mary University of London image from the Unlocking History Research Group archive.)

The items of study, called the Brienne Collection, are the contents of a 17th-century European postmaster's trunk of 3148 cataloged items with 577 letterpackets that have never been opened.[3-4] The X-ray microtomography scanner, developed at the laboratories of Queen Mary University of London’s dental research department, has high sensitivity that enabled it to image the types of ink in paper on these letters.[4] This scanner functions like a medical CT scanner, but it uses much more intense X-rays that allowed detection of metals in the inks.[4] The unfolding algorithm was developed by Amanda Ghassaei and Holly Jackson of MIT.[5] The source code is available from GitHub.[6] The algorithm successfully accomplished unfolding of the letters despite the thinness of the paper, and the very small gap between touching layers.[5] The document initially studied was a July 31, 1697, letter from Jacques Sennacques to his cousin, Pierre Le Pers, a French merchant in The Hague, for a certified copy of the death notice of Daniel Le Pers.[5] The algorithm can handle many other types of historical texts, such as books that are too fragile to open.[5] This research was supported by the Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research) and other organizations.[3,5]

computer unfolding of letter DB-1538 from the Brienne Collection, a collection that includes 577 letterpackets that have never been opened. (Still images from a Queen Mary University of London video by the Unlocking History Research Group. Click for larger image.[7])

References:

- Harry Edwin Burton, "The Optics of Euclid," J. Opt. Soc. Am., vol. 35 (1945), pp. 357-372 (PDF File from philomatica.org).

- Marvin Minsky, "Microscopy apparatus," US Patent no. 3,013,467, December 19, 1961 (Via Google Patents).

- Jana Dambrogio, Amanda Ghassaei, Daniel Starza Smith, Holly Jackson, Martin L. Demaine, Graham Davis, David Mills, Rebekah Ahrendt, Nadine Akkerman, David van der Linden & Erik D. Demaine, "Unlocking history through automated virtual unfolding of sealed documents imaged by X-ray microtomography," Nature Communications, vol. 12 (March 2, 2021), Article no. 1184. This is an open access article with a PDF file here.

- Secrets of sealed 17th century letters revealed by dental X-ray scanners, Queen Mary University of London Press Release No. 2021SMD, March 2, 2021.

- Researchers virtually open and read sealed historic letters, MIT Libraries Press Release, March 2, 2021.

- Unlocking History virtual-unfolding code by Amanda Ghassaei and Holly Jackson (Github).

- Queen Mary University of London animation of the computer unfolding of letter DB-1538 of the Brienne Collection.