Crystallization

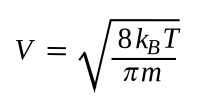

May 10, 2021 Atomism, the idea that every substance is constructed from fundamental indivisible components, started with the ancient Greek philosopher, Leucippus (fl. 5th century BC). The conjectured existence of such particles was even considered as late as 1714, when Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716) wrote about his atomic units, the monads, in his short treatise, Monadologie. Less than two centuries later, atomism left the realm of philosophy and entered the realm of science. A collection of atoms wouldn't be anything more than a gas unless they could join together. The Greek philosophers considered this problem, and their solution was to imagine that atoms had hooks on the outside that allowed them to coalesce (see figure). This Velcro chemistry was later refined into the theory of the chemical bond, first by Gilbert N. Lewis (1875-1946) in his 1916 valence bond theory, and later by Linus Pauling (1901-1994) in his ideas of resonant bonding and orbital hybridization.[1] I wrote about Lewis in an earlier article (Gilbert N. Lewis, November 16, 2011).

A diagram of hooked atoms and an engraving of Leucippus, originator of atomism. Is it any wonder that ancient seafarers and fishermen would consider hooks as a means to bind atoms? (Hooked atom diagram created using inkscape. Leucippus image, portion of a Wikimedia Commons image of a line engraving by S. Beyssent after Mlle C. Reyde from the Wellcome Trust, ICV no. 3727, photo no. V0003528. Click for larger image.)

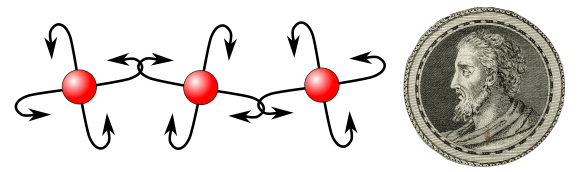

Not only do atoms coalesce, but they arrange themselves into ordered structures and form crystals. In fact, it's very difficult to produce an amorphous (noncrystalline) material. This is generally done by freezing in place the random atomic order of a liquid or gas by rapid cooling. One technique to achieve amorphous materials is splat cooling, also known as splat quenching. Another is melt spinning in which molten metal is formed into a thin ribbon of amorphous metal by contact with a rotating heat-sinking flywheel.

Left image, crystals of Halite (rock salt) created by slow crystallization from a concentrated salt solution at room temperature. Right image, the crystal structure of sodium chloride (NaCl) with the larger chlorine anions shown in green. (Left image; and, right image by Benjah-bmm27, both from Wikimedia Commons. Click for larger image.)

Polycrystalline materials are formed at slower cooling rates than amorphous materials, and the small crystal grains of polycrystalline metals can be enlarged by annealing. In annealing, the metal is kept hot for some time to allow atoms to migrate to more stable positions. Simulated annealing is an optimization technique based on this principle. Large crystals of silicon are grown using the Czochralski method at a growth rate of about a millimeter per minute. Crystals of neodymium-doped YAG (Nd:YAG), an important laser material, can only be grown at about a millimeter per hour, primarily because the atoms of not one, but several, elements need to find their proper lattice positions. The dimension of a unit cell of YAG is 1.19677 nanometers, so a growth rate of a millimeter per hour calculates to the addition of 232 unit cells per second; so, it takes just a little less than 5 milliseconds to add a layer of one unit cell to a growing crystal of YAG. This appears to be quite rapid, but the crystal is being formed from atoms that have a huge velocity in the liquid. We can calculate the mean thermal velocity of a yttrium atom, as follows:

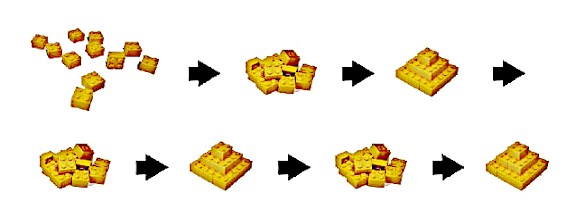

where kB is the Boltzmann constant (1.380649x10−23 J/K, in which a J/K is m2·kg/(s2·K) in SI base units), T is the absolute temperature, and m is the mass of a yttrium atom. The melting point of YAG is about 2250 K, and I've calculated the weight of a yttrium atom as 1.48x10-25 kg. This leads to a yttrium atom thermal velocity in the liquid of nearly a kilometer per second. During crystallization, there's obviously a lot of activity at the growth interface. An international team of scientists has just published a study that examined the early stage nucleation of crystals at the atomic level,[2-3] The team members were from Hanyang University (Ansan, Republic of Korea), the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST, Daejeon, Republic of Korea), Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL, Berkeley, California), Integrated Dynamic Electron Solutions, Inc. (Pleasanton, California), Seoul National University (Seoul, Republic of Korea), the Institute for Basic Science (IBS, Seoul, Republic of Korea), Yonsei University (Seoul, Republic of Korea), the University of California (Berkeley, California), and the Kavli Energy NanoSciences Institute (Berkeley, California). Their study showed the existence of dynamic and reversible fluctuations of developing nuclei between disordered and crystalline states as a gold crystal was formed on a graphene substrate.[2-3] According to a classical concept of crystal growth, crystals are formed one atom at a time.[3] Transient, high energy arrangements of these atoms are first formed, but these atoms rearrange to the lower energy forms of a stable crystal.[3] The present study finds that atoms are involved in a dynamic and reversible fluctuation between disordered and crystalline states while building crystal nuclei.[2] In the study, gold atoms don't just group together one-by-one or make a single irreversible transition, but they will self-organize, amorphize, and then reorganize many times on the path to their stable configuration.[3]

Crystal nuclei built from atoms, disordered, then built again. This is a Lego® reconstruction of an observed sequence of gold crystal formation. (Portion of a Berkeley Lab image).

It was found that the lifetime in the disordered state decreases with increasing atom cluster size.[2] For small nuclei, the binding energy per atom is enough to induce melting that will cause a partial collapse of an ordered cluster into a disordered state.[2] That's because crystal formation is an exothermic process.[3] However, when the nuclei crystals are large enough, they are locked into their ordered state.[3] The research team validated this process by computer simulation of the binding reaction between gold atoms and a nanocrystal.[3] This process of the formation of gold crystals on a graphene substrate was observed through the reduction of a precursor by the electron beam in an electron microscope.[2] The electron microscope had millisecond temporal resolution that allowed observation of the rapid dynamic structural fluctuations.[2-3] It captured atomic-resolution images at speeds up to 625 frames per second, about a hundred times faster than previous studies.[3] As study author, Peter Ercius of Lawrence Berkeley laboratory explains,

"Slower observations would miss this very fast, reversible process and just see a blur instead of the transitions, which explains why this nucleation behavior has never been seen before,"[3]The research team plans to view such transitions in other atomic systems to find whether it's a general process of nucleation.[3] The research was principally funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea. Other funding was from the United States Department of Energy, the Institute for Basic Science (Korea), the Samsung Science and Technology Foundation, and the United States National Science Foundation.[3]

References:

- Linus Pauling and The Nature of the Chemical Bond: A Documentary History - Special Collections - Oregon State University.

- Sungho Jeon, Taeyeong Heo, Sang-Yeon Hwang, Jim Ciston, Karen C. Bustillo, Bryan W. Reed, Jimin Ham, Sungsu Kang, Sungin Kim, Joowon Lim, Kitaek Lim, Ji Soo Kim, Min-Ho Kang, Ruth S. Bloom, Sukjoon Hong, Kwanpyo Kim, Alex Zett, Woo Youn Kim, Peter Ercius, Jungwon Park, and Won Chul Lee, "Reversible disorder-order transitions in atomic crystal nucleation," Science, vol. 371, no. 6528 (January 29, 2021), pp. 498-503, DOI: 10.1126/science.aaz7555.

- Clarissa Bhargava, "Revealing the Nano Big Bang – Scientists Observe the First Milliseconds of Crystal Formation," Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory Press Release, March 25, 2021.

- Revealing the Nano Big Bang in Crystal Formation, Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory YouTube video, March 24, 2021.