Entropy and Timekeeping

July 19, 2021 A typical household uses too many expendable (primary cell) batteries. There are so many of these that my township, which had its residents segregate all batteries for special disposal, now requires that just automotive batteries,nickel–cadmium (NiCad) batteries, and lithium batteries be segregated. It advises that "household batteries can be placed in regular trash." While wall clocks are now battery operated, I'm fortunate in having a recessed wall outlet above the kitchen sink at which an AC operated clock resides. This clock probably uses less than a watt of power to mechanically move its analog hands, and it's a good example of the Second Law of Thermodynamics in several ways. First, the Second Law of Thermodynamics, the entropy law, states that physical processes waste energy and wind-down, an idiom that relates to spring-wound clocks. The motor of my kitchen clock is likely just 60% efficient, so it's warm to the touch. The clock also makes a tick-tock sound that's just audible in the quiet of the night. The energy lost in heat and sound means that the clock is adding to the entropy of the universe. Clocks and the Second Law of Thermodynamics are also connected though the idea of the arrow of time first elucidated by preeminent physicist, Arthur Stanley Eddington (1882-1944), who also provided observational verification of Einstein's theory of general relativity. Everything in the universe becomes disordered as time increases, and this allows us to distinguish between the past and future and identify the direction of time.

Physicist, Arthur Stanley Eddington (1882-1944).

Eddington also provided observational verification of Einstein's theory of general relativity by observing the bending of starlight around the Sun during solar eclipse of May 29, 1919.

Astrometry was primitive in 1919, so Eddington's evidence in confirmation of relativity was tenuous, but sufficient to convince physicists of his era. A 1979 computer-assisted re-analysis of his original eclipse plates confirmed his conclusions.[1]

(United States Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, image ggbain.38064, via Wikimedia Commons, modified for artistic effect.)

My kitchen clock, the accuracy of which is derived from the frequency of the AC power lines, is a few seconds a day. However, atomic clocks have an accuracy that exceeds 109 seconds per day. The second is now defined as the "duration of 9,192,631,770 periods of the radiation corresponding to the transition between the two hyperfine levels of the ground state of the caesium-133 atom" (at absolute zero). I wrote about a ytterbium atomic clock in an earlier article (Ytterbium Atomic Clock, March 16, 2012) and also about a thorium-229 nuclear clock with an accuracy of one part in 1019 (Thorium Nuclear Clock, March 26, 2012). That's an accuracy of a tenth of a second over the age of the universe. A team of physicists and materials scientists from the University of Oxford (Oxford, United Kingdom), the Austrian Academy of Sciences (Vienna, Austria), Lancaster University (Lancaster, United Kingdom), and the Vienna University of Technology (TU Wien, Vienna, Austria). have recently published a different aspect of the thermodynamics of timekeeping.[2-4] They created a model clock based on a vibrating nanoscale membrane, and they demonstrated that it generates more entropy as its precision is increased. This has the consequence that hotter clocks are more precise. Their study, published in Physical Review X, is the first time that a measurement has been made of the entropy generated by a minimal clock.[4]

Skilled artist at work.

Artists' conceptions of scientific research are often exceptional, as this image illustrates.

One of the more famous representations of clocks in art is The Persistence of Memory, a 1931 painting of melting clocks by Salvador Dalí (1904-1989), presently on display at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

Physical chemist and Nobel Laureate, Ilya Prigogine (1917-2003) asked Dalí whether this painting was inspired by Einstein's theory of relativity. Dalí replied that it was a representation of Camembert cheese melting in the sun.

(Lancaster University image, Also available here. The Persistence of Memory can be viewed on the Museum of Modern Art website.)

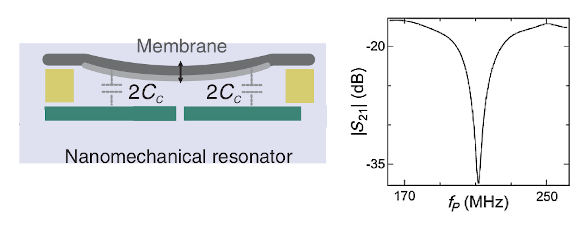

Clocks are machines; and, like every machine, they are subject to the laws of thermodynamics. Since the most accurate clocks operate through use of greater energy, we should suspect a fundamental connection between accuracy and energy consumption.[4] More precisely, since fluctuations limit clock accuracy at a fundamentally level, this suggests a connection between entropy and the accuracy of clock ticks.[2-3] In the present study, the research team demonstrated that a simple mechanical clock based on a nanoscale thickness vibrating membrane, the vibration of which is driven by heat, increases entropy as its precision is increased.[3] Previous studies of quantum clocks found a linear proportionality between their accuracy and their entropy production, but it was unknown whether this applied to classical clocks as well.[2-3] Furthermore, such a classical clock experiment is difficult, since keeping track of the input and output energy is difficult.[3] This first experimental investigation of the thermodynamics of a classical clock showed that it works the same as the quantum clocks; that is, entropy and accuracy are linearly related.[2] The clock designed for the experiment was a silicon nitride membrane suspended over metal electrodes for excitation of vibrations.[3] The vibrating membrane was a few tens of nanometers thick and 1.5 millimeters in size, and each oscillation of the membrane produced one electrical clock tick.[3-4] To measure the thermodynamics of the process, the membrane was heated while the flow of energy through the clock was measured electrically.[4]

On the left, a schematic diagram of the silicon nitride nanoresonator used in the clock entropy experiments. Shown in the image are the capacitances used for resonance detection. The resonant spectrum is shown on the right. (Potions of fig. 2 of ref. 2, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.)

Increasing the heat caused an increase in the vibration amplitude, which improved the precision of the clock.[3] It was found that the entropy, as determined by the lost heat, increased linearly with the precision, in agreement with the result from quantum clocks with a different proportionality constant.[2-3] The experiment confirmed that the more energy consumed by a clock, the more accurate is its timekeeping.[4] To make the clock twice as accurate, twice as much heat needs to be applied.[4] According to theory, an ordinary wristwatch with an accuracy of one part in ten million must consume at least a microwatt of power per tick, while it actuality it consumes just a few times this amount.[4]

References:

- Daniel Kennefick, "Not Only Because of Theory: Dyson, Eddington and the Competing Myths of the 1919 Eclipse Expedition," arXiv, September 5, 2007.

- A. N. Pearson, Y. Guryanova, P. Erker, E. A. Laird, G. A. D. Briggs, M. Huber, and N. Ares, "Measuring the Thermodynamic Cost of Timekeeping," Phys. Rev. X, vol. 11, no. 2 (May 6, 2021), article no. 021029, DOI:https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevX.11.021029. This is an open access article with a PDF file here

- Michael Schirber, "Keeping Time on Entropy's Dime," Physics, vol. 14, no. 54, May 6, 2021.

- Why hotter clocks are more accurate, University of Lancaster Press Release, May 10, 2021.