Demons in Science

January 25, 2021 The supernatural beings known as angels are a part of many religions, and they are mentioned often in the Bible and other Judeo-Christian religious texts. Their function is to relay the intentions of God to humans, and the word, angel, derives from the Greek word, ἄγγελος, angelos (messenger). The number of angels, as stated in Revelation 5:11, is ten thousand times ten thousand, or 100 million.

An angel (left) and a demon. Angels are often depicted playing a harp. Popular culture says that the fiddle is the devil's musical instrument. (Left image, an angel from The Celestial Country, a 1900 publication by Edwin S. Gorham; right image, an 1863 illustration by Louis Le Breton (1818-1866) from Tables tournantes dans le Dictionnaire infernal par Collin de Plancy; both from Wikimedia Commons)

While every experimenter hopes that a guardian angel is assisting him in his experiments, there are no specific angels mentioned in the scientific literature. There are, however, a few demons, and these are discussed in a recent book, Bedeviled: A Shadow History of Demons, by Jimena Canales.[1] This book was reviewed in a recent issue of Science by Jan G. Michel of the Department of Philosophy of Religion and Science, Ruhr-Universität Bochum (Bochum, Germany).[2] Alphonso de Spina (fl. 1500), a Spanish Franciscan Catholic bishop, somehow determined that the number of demons was 133,316,666. This number is nearly a factor of five too large, if we believe that the traditional number of demons is one third of the angels. Paradise Lost, a 1667 epic poem by John Milton (1608–1674), states that Satan, in his rebellion against God, "Drew after him the third part of Heaven's host."[3] The most famous quotation from Paradise Lost is Satan's declaration, "Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven." In Bedeviled: A Shadow History of Demons, Canales writes about three principal demons relating to science; namely, Laplace's demon, Maxwell's demon, and Descartes' demon. Laplace's demon, as imagined by French polymath, Pierre-Simon Laplace (1749-1827), has knowledge of the precise location and momentum vector of every atom in the universe. This knowledge allows a calculation of any future state of the universe according to the laws of classical mechanics. There have been many arguments for why this demon would not be successful in its calculations. We can't invoke quantum mechanics, since the realm of the question is the classical mechanics known to Laplace. Furthermore, we can't invoke chaos theory, since all quantities are supposedly known to adequate precision.

Three demon masters, René Descartes (1596-1650), Pierre-Simon Laplace (1749-1827), and James Clerk Maxwell (1831-1879), responsible for the eponymous Laplace's demon, Maxwell's demon, and Descartes' demon. (Portrait of René Descartes by Gérard Edelinck from a bust by Frans Hals (left), image of Pierre-Simon Laplace (center), and an engraving of James Clerk Maxwell by G. J. Stodart from a photograph by Fergus of Greenock (right) all from Wikimedia Commons.)

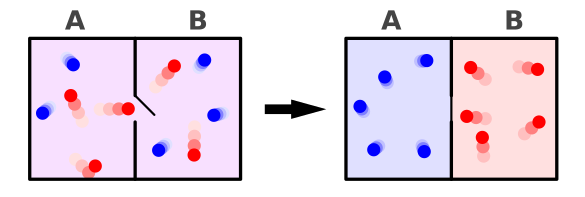

The most plausible reason for the impossibility of Laplace's demon's success is the computational power required. All computation requires a memory of a calculation's intermediate terms, and the universe has a limit on information content. This limit amounts to 10120 bits, a number derived from fundamental physical constants, and this would be the minimum size of a computation for simulating the universe.[4-6] That number, combined with the limitation imposed by the speed of light on information transfer, requires that any computation that needs more data than this can't be done in less time than the age of the universe. This presumes that the demon is bound by the laws of physics, a necessary condition; otherwise, anything would be possible. Maxwell's demon is a part of a thought experiment devised in 1867 by physicist, James Clerk Maxwell (1831-1879). In this thought experiment, a demon violates the second law of thermodynamics, the law concerning entropy that proves that a perpetual motion machine can't function by extracting environmental thermal energy to produce mechanical work. The demon controls a door between two gas-filled chambers. He opens the door to allow only faster (hotter) gas molecules to enter one chamber, and only slower (colder) gas molecules to pass into the other. Maxwell's demon can't function as envisioned, since he's a part of the thermodynamic system. He creates more entropy than he could ever eliminate in doing his task, since the act of acquiring information on molecular speed expends energy.

Principle of Maxwell's demon. The door separating the two chambers opens to allow only hot gas molecules to pass from A to B, and cold molecules to pass from B to A. (Modified Wikimedia Commons image by Htkym.)

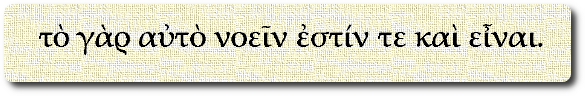

Descartes' demon acts in a way that precludes any scientific truth. As imagined by French mathematician, scientist, and philosopher, René Descartes (1596-1650) in his 1641 Meditations on First Philosophy, this demon presents to men a complete illusion of an external world. As Descartes writes, "I shall consider myself as not having hands or eyes, or flesh, or blood or senses, but as falsely believing that I have all these things." You might see an analogy of this with the recent idea that we are part of a computer simulation. Descartes dismisses this idea by stating, "je pense, donc je suis," which is most commonly rendered as cogito, ergo sum; that is, "I think, therefore I am." The reasoning is that such self-awareness could not be manipulated. This idea was earlier stated around 500 BC by Parmenides of Elea (fl. late sixth - early fifth century BC). Parmenides wrote in his book, On Nature, in the section known as the way of truth, "For it is the same thing that can be thought and that can be."[7]

"For it is the same thing that can be thought and that can be." A portion of On Nature by Parmenides of Elea. (From Ref. 7.)[7]

While on the topic of demons, we should also address the interesting question of which place is hotter, heaven or hell. Heaven is often associated with a bright white light, while hell is a place of fire and brimstone, brimstone being an archaic term for sulfur. The melting point of sulfur is 115.21 °C (388.36 K, 239.38 °F), and its boiling point is 444.6 °C (717.8 K, 832.3 °F), so burning sulfur can have a temperature between those extremes (assuming atmospheric pressure). The temperature of a blackbody emitting white light is 5,225°C (5,500 K, 9440.33 °F).

References:

- Jimena Canales, "Bedeviled: A Shadow History of Demons in Science," Princeton University Press, November 10, 2020, 416 pp., ISBN: 978-0691175324 (via Amazon).

- Jan G. Michel, "Imaginary demons and scientific discoveries," Science, vol. 370, no. 6518 (November 13, 2020), p. 772, DOI: 10.1126/science.abd9851.

- John Milton, "Paradise Lost," at Project Gutenberg.

- S. Lloyd, "Ultimate physical limits to computation," Nature, vol. 406, pp. 1047-1054 (August 31, 2000). https://doi.org/10.1038/35023282.

- Seth Lloyd, "Computational Capacity of the Universe," Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 88, Article no. 237901, May 24, 2002, DOI:https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.237901.

- J.R. Minkel, "If the Universe Were a Computer," Physical Review Focus, vol. 9, no. 27 (May 24, 2002).

- Parmenides, "Fragments," Original Greek text by Diels, English translation by John Burnet, PDF File from Philoctetes.