E. F. Schumacher and Sustainability

November 8, 2021 Although some economic principles of maintaining a farm were contained in the Works and Days by Hesiod (c. 700 BC), the first book on economics is the Oeconomicus (Οικονομικός, "household management") by Xenophon (c. 430-354 BC). It can be seen that our word, "economics," is taken from the title of this book. Xenophon's concept of economics as household management distinguishes it from the later works on political economics by Plato (c. 425- 347 BC) (The Republic, c. 370 BC) and Aristotle (384-322 BC) (Politics, c. 350 BC).

A passage from Hesiod's Works and Days. "For now truly is a race of iron, and men never rest from labor and sorrow by day, and from perishing by night; and the gods shall lay sore trouble upon them." (Hesiod, Works and Days, ll. 176-178, via Project Perseus)

Before the later half of the 20th century, economics was more like philosophy than science. Economics, just like anthropology, was more akin to telling a good story than making predictions. A good example of this is the 1899 book, The Theory of the Leisure Class, by economist, Thorstein Veblen (1857-1929) (a.k.a., Torsten Veblen).[1] This book is known for the first use of the term, conspicuous consumption, which is the purchase of lavishly expensive, or ephemeral and impractical, goods and services simply as a way of displaying income or wealth. I wrote about Veblen in an earlier article (The Physics of Inequality, May 11, 2017). My undergraduate economics textbook was Economics, by Paul Samuelson (1915-2009), the first recipient of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1970. As I remember, this mid-1960s edition of this book had a single equation, possibly one relating net national product with gross national product. It was an arithmetic equation easily understood by an elementary school student. Economics began to change in the mid-20th century with the advent of electronic computers and the subsequent creation of the Internet.[2] The availability of easily accessed data sets, coupled with a computer's ability to validate economic models based on these data, transformed economics from a field of philosophy to the highly mathematical discipline it is today. One quick look at recent economics papers posted to arXiv will offer a quick validation of this computerization of economics.[2-4] German-British economist and statistician, E. F. (Fritz) Schumacher (1911-1977), was one of the last influential philosophical economists. As if applying Ockham's razor to production of goods, Schumacher decried his world's "bigger is better" technological means of production and advocated a small is beautiful approach. His 1973 book, Small Is Beautiful: A Study of Economics As If People Mattered, is considered to be one of the most influential books published since World War II.[5] Publication of this book coincided with the 1973 oil crisis, which provided immediate evidence for the thesis of this book.

E. F. (Fritz) Schumacher (1911-1977).

In a 1978 documentary, Schumacher was thinking like a true thermodynamicist when he said, "Why, then, start-off with a nuclear reaction which has a million degrees in order, finally, to get thirty degrees room temperature."[6]

(Screenshot from a National Film Board of Canada video.[6])

In his book, Schumacher declared that the modern economy is unsustainable, since natural resources, such as the fossil fuels that fueled the subsequent 1973 oil crisis, are not renewable, and pollution would take its toll on the Earth.[5] An effective countermeasure is the way that things were done before our industrial technology.[5] In a a 1977 documentary filmed shortly before his death, Schumacher bemoans the many mindless tasks that abound in modern production.[6] Although my scientific career was more intellectually challenging than working on an assembly line, I was still subjected to such mindless tasks as writing monthly progress reports that were never read. Some of Schumacher's arguments against runaway technology are distilled into the following two excerpts from the first part of his book.[5]

"We are estranged from reality and inclined to treat as valueless everything that we have not made ourselves... Modern man does not experience himself as a part of nature but as an outside force destined to dominate and conquer it. He even talks of a battle with nature, forgetting that, if he won the battle, he would find himself on the losing side."It's become difficult to obtain the many natural resources required for today's products. It's common knowledge that battery lithium and magnetic rare earths presently top the list of critical material facing shortage. In 2018, the United States Department of the Interior published a list of 35 minerals considered to be critical.[7] These are aluminum (bauxite), antimony, arsenic, barite, beryllium, bismuth, cesium, chromium, cobalt, fluorspar, gallium, germanium, graphite (natural), hafnium, helium, indium, lithium, magnesium, manganese, niobium, platinum group metals, potash, the rare earth elements group, rhenium, rubidium, scandium, strontium, tantalum, tellurium, tin, titanium, tungsten, uranium, vanadium, and zirconium.[7] There are peripheral economic issues that surround these critical materials. Recycling is a sure way to ensure supply. Also, replacement of rotating disk media, whose actuators contain rare earth magnets, with solid state drives would reduce demand for rare earth metals. Mining and refining of metals requires energy; and, as the principal mineral sources are depleted, secondary sources need more energy still for extraction and refining. Our quest for renewable energy sources is impeded by the fact that wind turbines and solar panels need several elements on the critical elements list. An example of technology contributing to waste that didn't exist in Schumacher's time is the present tendency for makers of consumer electronic devices to drop software support for their devices long before the hardware wears out. As one small measure to reduce electronic waste, the European Union has proposed that electronic devices, such as cellphones and tablet computers, all contain a common USB-C charging port on their devices so chargers and cables can be shared and reused.[9]

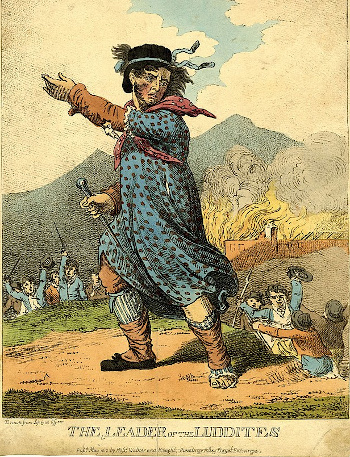

Ned Ludd, "King of the Luddites."

Ludd supposedly broke two knitting machines in Leicester, England, in 1779 in a fit of rage.

The Luddites were workers who produced textile articles in small workshops and found that were being replaced by machines in large factories. In the period 1811-1816 their movement destroyed many such machines until it was suppressed by military force.

Schumacher is often categorized as a Neo-Luddite, but he is distinguished from a Luddite by proposing economic alternatives to the rampant replacement of workers by runaway technology and automation.

(Wikimedia Commons image dating from 1812.)

References:

- Thorstein Veblen, "The Theory of the Leisure Class," 1.4 MB PDF File, via Law in Contemporary Society Web Site, Columbia Law School.

- Call for Papers, The Computerization of Economics - Computers, Programming, and the Internet in the History of Economics, OEconomia – Histoire/Epistémologie/Philosophie, June, 2021.

- Beatrice Cherrier, "How the computer transformed economics. And didn't," Institute for New Economic Thinking, May 19, 2016.

- The computerization of economics: a chronology (in progress), Beatrice Cherrier's blog, February 7, 2016.

- E. F. Schumacher, Small Is Beautiful, PDF version of the book at the Department of Electrical Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, Website.

- Small Is Beautiful: Impressions of Fritz Schumacher, Donald Brittain, Barrie Howells, and Douglas Kiefer, Directors, National Film Board of Canada, 1978. Also available as Bigger isn't better - the renegade 'Buddhist economics' of E F Schumacher, Donald Brittain, Barrie Howells, and Douglas Kiefer, Directors, Aeon.co.

- Final List of Critical Minerals 2018, A Notice by the Interior Department on 05/18/2018, 83 FR 23295, pp. 23295-23296.

- Critical Minerals and Materials: U.S. Department of Energy’s Strategy to Support Domestic Critical Mineral and Material Supply Chains (FY 2021-FY 2031), US Department of Energy (PDF File).

- Pulling the plug on consumer frustration and e-waste: Commission proposes a common charger for electronic devices, European Commission of the European Union Press release, September 23, 2021.