Whiskey

January 20, 2020 Early in our marriage, I accompanied my wife on her job interview at a university research department. While I waited for her, I spent my time browsing in the department's library. There I found an interesting newsletter that listed actions by the US Food and Drug Administration. One item caught my attention. Someone had drilled holes in cheese in order to sell it as properly aged Swiss cheese. The cheese was seized and destroyed for adulteration.

A block of Swiss cheese.

Swiss cheese with larger "eyes" has a deeper flavor, since it has undergone a longer fermentation.

Annual Swiss cheese production in the United States is somewhat more than 300 million pounds.

(Wikimedia Commons image.)

Swiss cheese is a generic term for cheese that resembles the actual Swiss cheese, Emmental. While anyone can sell an Emmental cheese, real Emmentaler Switzerland cheese is a protected designation; that is, the name can only be used for cheese made in a specific geographical area, very much like real Champagne is only produced in the Champagne region of France, about 100 miles east of Paris. Specific designations exist for wines and cheeses, but also for cognac, sausages, olive oils, and balsamic vinegar, among many other foods. Some cheese examples include Gorgonzola, camembert, roquefort, and Grana Padano. I wrote about protected designation of origin (PDO), including the Italian Denominazione di Origine Protetta, in a previous article (Neolithic Cheese, October 15, 2018) Counterfeits, such as the adulterated Swiss cheese that I mentioned above, harm the reputation of the actual product. As a consequence, government agencies use scientific forensic techniques to identify such counterfeit products. Since fine wines are an expensive product, chemists have been developing techniques for the forensic analysis of wine. One study by a team of chemists from Poland and Spain identified 27 parameters describing chemical compositions for verification of a wine's authenticity.[1] They used a likelihood ratio analysis to verify the authenticity of 178 samples of the three Italian wine brands, Barolo, Barbera, and Grignolino, with 90% certainty.[1]

Une bonne goutte! (A good drop!), an oil on canvas painting by Joseph-Noël Sylvestre (1847–1926).

Human senses gave a very good account of wine type and quality before analytical chemistry entered the scene.

There's been research on an electronic tongue. I wrote about such a device for analysis of beer in an earlier article (Beer Tongue, February 10, 2014)

(Wikimedia Commons image.)

Physicists have also applied their skill to wine forensics. Cesium 137 (137Cs) is a radioactive isotope with a half-life of 30.17 years. This short half-life means that this isotope was not present in the environment until it was created by nuclear weapon testing beginning with the Trinity nuclear test on July 16, 1945.[2] Wine created after this date will emit small amounts of gamma radiation by nuclear fission, and this radiation can be seen with a sensitive detector. As a consequence, new wine sold in vintage bottles of expensive varieties can be detected. Additional cesium 137 was created during the 1986 accident at the Chernobyl reactor and the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi disaster. Apparently, no cesium 137 was released during the Three Mile Island accident in 1979. Wine lovers need not worry that much about radiation in their wine. It's so small that detection must be done in laboratories deep underground, and the lead shielding for the detector must be made from lead that was smelted prior to nuclear testing.[2] Physicists have also found a different method of sorting another alcoholic beverage. American whiskey can be distinguished from Scotch whiskey (usually spelled, whisky, without the e) by image analysis of the residue left when drops of these evaporate.[3-7] This isn't the first time that residues from evaporated liquids have been studied. As I reported in three previous articles, Coffee Ring Physics, February 11, 2013, Coffee Rings, December 10, 2010 and Coffee Rings (Part II), August 25, 2011, coffee ring formation has been studied. Coffee rings form from the deposition of solid particles from the coffee colloid. The ring shape is a consequence of the outward flow of these suspended particles.

A coffee ring.

Physical laws, such as gravitation and surface tension, and conservation laws, such as minimization of surface energy, create natural objects with very similar forms.

A biologist will see a similarity between this image and that of a cell, and an astronomer might mistake this as an asteroid.

(Wikimedia Commons image by Okin.)

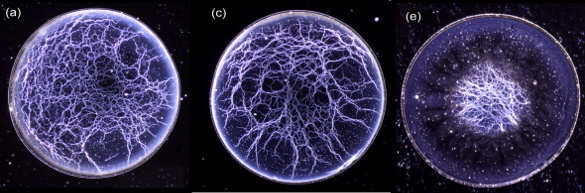

Authors from the University of Louisville (Louisville, Kentucky) presented their research on whiskey analysis in a recent paper at Physical Review Fluids, and as a poster paper entitled, "Whiskey Webs: Microscale "fingerprints" of bourbon whiskey," at the 71th Annual Meeting of the APS Division of Fluid Dynamics (November 18, 2018 - November 20, 2018).[3-5] Science progresses by extending previous research. In this case, the Kentucky research team was inspired by a 2016 paper in Physical Review Letters.[6-7] They discovered that droplets of whiskey aged in new, charred barrels, that is American whiskey, produced a pattern reminiscent of the blood-vessel network of a human eye after evaporation.[4] Not only that, but such patterns acted like unique fingerprints of the whiskey type and age.[4] Scotch whiskey derives its flavor from its aging in old, recycled barrels.[4] American whiskey, such as bourbon, is aged in new, charred, oak barrels.[4] The different aging processes leads to differences in chemical composition, and this appears to manifest itself in the residue patterns seen from evaporated drops, with the American whiskey leaving web-like patterns that are absent for other liquors.[4]

Web-like patterns in evaporated droplets of American whiskey. These patterns are for (a) Four Roses™ at 22.5% Alcohol by volume (ABN), (c) Maker's Mark™ Cask Strength™ at 22.5% ABV, and (e) Pappy Van Winkle's Family Reserve™ 23 Year™ at 25% ABV. (Portions of fig. 3 of ref.3, published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.)

The research team speculates that these web patterns arise from chemical compounds extracted from the charred barrel wood by the aging whiskey.[4] These molecules agglomerate, then collapse into the two-dimensional residue pattern after evaporation. They intend to test this hypothesis by placing tracer molecules inside the drops to visualize movement during the evaporation process.[4]

References:

- Agnieszka Martyna, Grzegorz Zadora, Ivana Stanimirova, and Daniel Ramos, "Wine authenticity verification as a forensic problem: An application of likelihood ratio test to label verification," Food Chemistry, vol. 150 (May 1, 2014), pp. 287-295, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.10.111.

- How Atomic Particles Helped Solve A Wine Fraud Mystery, NPR Morning Edition, The Kitchen Sisters, June 3, 2014.

- Stuart J. Williams, Martin J. Brown VI, and Adam D. Carrithers, "Whiskey webs: Microscale "fingerprints" of bourbon whiskey," Phys. Rev. Fluids, vol. 4, no. 10 (October 24, 2019), Article no. 100511, DOI:https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevFluids.4.100511.

- Matteo Rini, "Synopsis: Telling Whiskey from Whisky," Physics, October 24, 2019.

- Stuart J. Williams, Martin J. Brown, VI, and Adam D. Carrithers, "Whiskey webs: Microscale "fingerprints" of bourbon whiskey," 71th Annual Meeting of the APS Division of Fluid Dynamics (November 18, 2018 — November 20, 2018), Poster P0002, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1103/APS.DFD.2018.GFM.P0002. The poster appears at the Gallery of Fluid Motion.

- Hyoungsoo Kim, François Boulogne, Eujin Um, Ian Jacobi, Ernie Button, and Howard A. Stone, "Controlled Uniform Coating from the Interplay of Marangoni Flows and Surface-Adsorbed Macromolecules," Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 116, no. 12 (March 25, 2016), Article no. 124501, DOI:https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.124501.

- Michael Schirber, "Synopsis: Whisky-Inspired Coatings," Physics, March 24, 2016.