Short Words

October 19, 2020 The American author, Kurt Vonnegut (1922-2007), is known as a writer of science fiction, but his novels are widely read, since their scientific content serves as a vehicle for his unique perspective on life. I wrote about his ice-nine in an earlier article (Fictional Materials, April 21, 2016). Ice-nine, not to be confused with the actual ice-IX phase of water, is a fictional material in Vonnegut's novel, Cat's Cradle. Vonnegut's phase of water ice has the dangerous physical that it will spontaneously crystallize ordinary water into ice-nine under normal temperatures and pressures. Unfortunately, this phase of water is stable, and it will only melt at 45.8 degrees Celsius. This well above Earth ambient temperature even under the worst global warming scenario. Ice-nine eventually leads to the solidification of all the world's water, and destruction of life on Earth. Vonnegut said that he got this idea from 1932 Nobel Chemistry Laureate, Irving Langmuir. Langmuir had apparently suggested this as a story line to H. G. Wells, and Vonnegut heard about it while he was working in the public relations department at General Electric. Vonnegut considered the Ice-Nine idea to be free for him to use after both Langmuir and Wells had died.

Kurt Vonnegut explaining his concept of "story arcs" at Case Western Reserve University in 2004.

(Screenshot from a YouTube video by Case Western Reserve University, November 29, 2016.)[1]

As contrasted with many authors who inflate their prose with too many words, Vonnegut's books contain less literary allusion. His books are short, and they can been read in a single sitting of a few hours. Since Vonnegut was technically educated, he devised a theory of literary plot development, graphically illustrated as story arcs. You can learn about these in a YouTube video of a February 4, 2004, lecture he gave at Case Western Reserve University (Cleveland, Ohio) (The story arc portion starts at 37:35 in this 54:56 lecture).[1] As Vonnegut said in this lecture, "... I have tried to bring scientific thinking to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Literary_criticism, and there's been very little gratitude for this." Vonnegut's story arc analysis requires considerable interpretation of story text, and it won't be done by computers until artificial intelligence is somewhat more developed. However, computer analysis of literature using words and an elementary knowledge of grammar has been with us for quite some time. It's done such things as determining that multiple authors had a hand in writing books of the Bible, and piecing together fragments of text into a readable version of the Dead Sea Scrolls.[2] A literary analysis feature has been present on personal computer word processors since the earliest days of personal computing. I've written about these Flesch-Kincaid readability tests[3] in two earlier articles (Readability and Word Length, September 14, 2012, and Readability, February 12, 2014). I've written a short C language program (source code here) that calculates these scores using some simplified analysis. The Flesch-Kincaid tests are based on the simple idea that longer words and sentences are more difficult than short words and short sentences. This simplification ignores the fact that there are many short archaic and technical words unknown to students. The research for these tests was funded by the US military, which wanted to ensure that their training materials and maintenance manuals were understood by its recruits. The two measures of readability are the Flesch-Kincaid grade level and the Flesch reading ease index, calculated as follows:

Flesch-Kincaid Grade =Words, sentences and syllables in these formulas are the total counts of these objects in the manuscript. The scale for reading is aligned with age group; viz., 90->100 = 11 year old, 60->70 = 13-15 year old, and 0->30 = college graduates. The grade level is for school grade levels in the United States. The articles in this blog are at about a tenth grade level, and my three science fiction novels have a very accessible sixth grade rating.

(0.39*(words/sentences))+(11.8*(syllables/words))-15.59 Flesch Reading Ease =

205.835 - (1.015*(words/sentences))-(84.6*(syllables/words))

"Headless Body in Topless Bar" was the actual headline on the front page of the April 15, 1983, edition of The New York Post.[4]

Some publishers of supermarket tabloids use readability scores to ensure that their content is at the reading level of purchasers at the checkout.

(Created using Inkscape.)

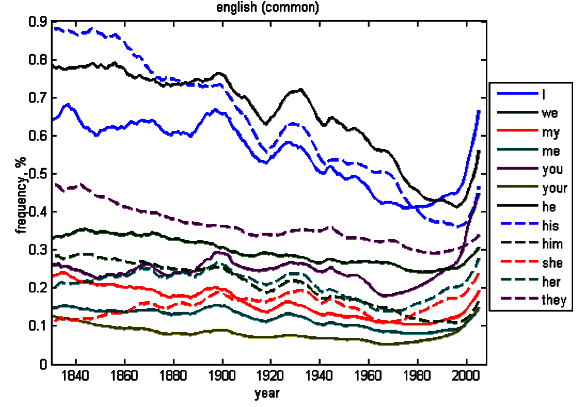

A 2012 study by scientists at the Kazan Federal University (Kazan, Russia) examined the Google Books corpus to determine trends in word usage.[5] They found that the average word length of American English declined from 4.8 to 4.3 characters in the period from 1975-2008, while that of British English increased from 4.9-5.1 over the same period.[5] They also found the interesting temporal trend in the use of personal pronouns from 1700 to 2008 (see graph).[5]

Personal pronoun usage from 1835-2008. (Fig. 6 from ref. 5, via arXiv.)

A moment's reflection will reveal that just about every narrative, from trivial television dramas and romance novels to Oedipus Rex, has a progression from a beginning through a middle to an end. While any narrative has its specific characters and setting, it seems that all narratives have a structure that's independent of such details. Computer analysis has enabled a way to quantify this structure, and a tally of positive vs negative "emotion" words has given a means of sorting rags-to-riches stories from tragedies.

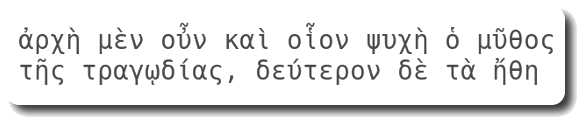

Literary analysis was done as early as 335 BC. This is a portion of Part VI of the c. 335 Poetics of Aristotle (384-322 BC). This translates as "The plot then is the first principle and as it were the soul of tragedy: character comes second." (Via the Tufts University Department of the Classics Perseus Digital Library

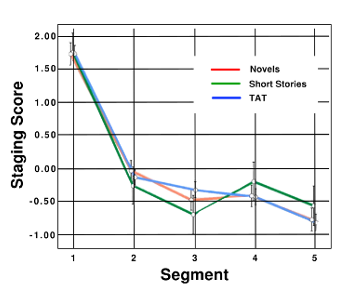

A simpler method of computer analysis has just been published by psychologists from Lancaster University (Lancaster, UK) and the University of Texas at Austin (Austin, Texas). Their study is published as an open access paper in Science Advances.[6-9] They did a computer analysis on about 40,000 narratives that included such things as novels, screenplays, 28,664 New York Times articles, 1,580 US Supreme Court opinions, and 2,226 TED talks.[6-7] The analysis revealed a common structure in most of three primary processes; namely, staging, plot progression, and cognitive tension, which was absent in factual texts.[6] Since the narrative structure was independent of topic, the researchers reasoned that it should be apparent in content-free words, function words, short connector words such as pronouns (she, they), preposition, articles (a, the), conjunctions, and negations Such function words also include auxiliary verbs, and non referential adverbs, such as "so" and "really."[6-7] There is just a small number of common function words in English, fewer than 200, but they account for 50 to 60% of all words that are written, or said.[6] These small function words appear in a similar pattern across most narratives, independent of length or type.[7] The common structure of the narratives followed these three stages:[7]

Staging, the start of the narrative in which many prepositions and articles were used, apparently as a means set the scene and convey basic information about concepts and characters in the story (e.g., "the laboratory,").Says lead author of the study, Ryan Boyd, an assistant professor at Lancaster University,[7]

Plot progression in which more interactional language is used, including auxiliary verbs, adverbs and pronouns (e.g., "his laboratory.").

Cognitive tension using action words, such as "think" and "cause," that brings the narrative to a conclusion.

"If we want to connect with an audience, we have to appreciate what information they need, but don’t yet have... At the most fundamental level, humans need a flood of logic language at the beginning of a story to make sense of it, followed by a rising stream of action information to convey the actual plot of the story."

Use of articles and prepositions over the course of a narrative.

TAT is a collection of 14,419 brief stories written in response to a standardized thematic apperception test by individuals who accessed a website maintained by an author of the study.

(Created using data from a YouTube Video.[8])

References:

- Kurt Vonnegut February 4, 2004, Lecture at Case Western Reserve University, YouTube Video, November 29, 2016. A shorter version with Spanish subtitles can be found here.

- Ron Grossman, "Computer Generates Bootleg Copy Of Dead Sea Scrolls." Chicago Tribune, September 4, 1991.

- J. Peter Kincaid, Richard Braby and John E. Mears, "Electronic authoring and delivery of technical information," Journal of Instructional Development, vol. 11, no. 2 (June, 1988), pp. 8-13.

- Steve Cuozzo, "The genius behind 'Headless Body in Topless Bar' headline dies at 74," New York Post, June 9, 2015.

- Vladimir V. Bochkarev, Anna V. Shevlyakova and Valery D. Solovyev, "Average word length dynamics as indicator of cultural changes in society," Social Evolution & History. vol. 14, no. 2 (September, 2015), pp. 153-175. Also at arXiv.

- Ryan L. Boyd, Kate G. Blackburn and James W. Pennebaker, "The narrative arc: Revealing core narrative structures through text analysis," Science Advances, vol. 6, no. 32 (August 7 2020), Article no. eaba2196, DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aba2196. This is an open access article with a PDF file available here.

- Authors' 'Invisible' Words Reveal Blueprint for Storytelling, University of Texas Press Release, August 7, 2020.

- Science Advances: The Arc of Narrative, YouTube Video by Ryan Boyd, August 7, 2020.

- The Arc of Narrative website.

- Aristotle, "Poetics," S. H. Butcher, Trans., at the The Internet Classics Archive by Daniel C. Stevenson.