The Multifaceted William Shockley

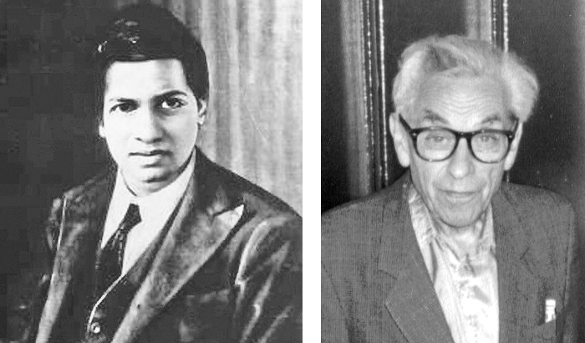

July 20, 2020 Scientists and mathematicians seem to act differently than most individuals. There are both positive and negative aspects of this. On the positive side, we have data-driven decision making that's so much needed in today's world. The negative side is illustrated in the lives of many such prominent people. For mathematicians, there's the obsession with work that likely contributed to the early death of Srinivasa Ramanujan (1887-1920) at age 32. Paul Erdős (1913-1996) was another workaholic mathematician; but, unlike Ramanujan, Erdős lived to be 83. Erdős lived his later life as a homeless person. He relied on his mathematician colleagues to provide occasional room and board and to tend to his finances.

Srinivasa Ramanujan (1887-1920) (left), and Paul Erdős (1913-1996) (right). (Left image and right image, both from Wikimedia Commons.)

Mathematician, Kurt Gödel, famous for his incompleteness theorems, died from malnutrition by believing that people were trying to poison him. John Forbes Nash, who shared the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1994 for the development of game theory, suffered from paranoid schizophrenia, as detailed in Sylvia Nasar's book, A Beautiful Mind.[1] Nash fortunately recovered from his mental illness, only to be killed with his wife in a tragic 2015 automobile accident after his award of the Abel Prize. It should be noted that a contributing cause of death was the couple's not wearing seat belts. Among physicists, the taciturn, Paul Dirac (1902-1984), stands as an interesting example, so much so that one of his biographies is entitled, The Strangest Man.[2] The title of this biography, by Graham Farmelo, apparently derives from Niels Bohr's assessment that Dirac was the "the strangest man" who had visited his laboratory. It's said that Dirac's Cambridge University colleagues invented a unit, the dirac, which had a value of one word per hour.[2] While more curious than strange, physicist, Richard Feynman (1918-1988), is well known for his extra-physical interests and activities.[3] Physicist, William Shockley (1910-1989), was co-inventor of the transistor, he shared in the 1956 Nobel Prize for Physics with his Bell Labs colleagues, John Bardeen (1908-1991) and Walter Brattain (1902-1987), and he is listed as an inventor on more than 90 US patents. Shockley had a generally paranoid and domineering personality, as evidenced by his leadership at the Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory. These traits became exaggerated after he was seriously injured in an automobile accident in July, 1961. While he seemed to recover fully from his injuries after a few months, he became an embarrassment to Stanford University; and, to Bell Labs, for which he remained a consultant. He became combative and socially isolated, and became estranged from his children, who only learned of his death in 1989 from news reports. He promoted racial superiority and eugenics.

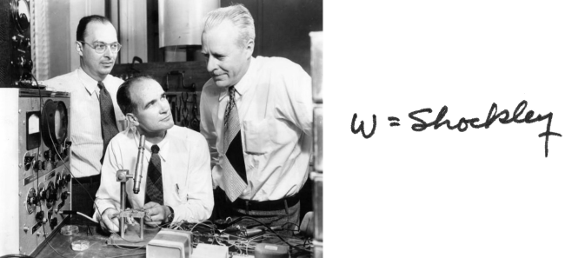

This photograph shows the three inventors of the transistor: John Bardeen (1908-1991) (left), William Shockley (1910-1989) (center) and Walter Brattain (1902-1987) (right), as shown in a 1948 Bell Labs press release in connection with the announcement of this invention on June 30, 1948). As demonstrated by the invention of the telephone and laser, all important inventions come with controversy. Shockley was not a designated inventor on the 1948 patent application for the transistor, and it was a Bell Labs political decision that he should be considered one of the inventors, since he was one of the leaders of the solid state physics group that had Bardeen and Brattain among its members.

On the right is Shockley's signature, scanned from a 1980 letter from him in which he included a requested reprint of a paper on dislocations in electronic materials, and also some of his racist propaganda.

(Left, Wikimedia Commons image. Right, a scan from my personal files. Click for larger image.)

The early life of a scientist can be predictive of his later life. Shockley was born in London, England, to American parents who were technical professionals.[4] His father, a mining engineer, and mother, a mineral surveyor, settled in Palo Alto, California, when Shockley was three years of age. They educated him at home until he was eight, since they thought they could do a better at teaching him than the public schools.[4] His parents emphasized mathematics and science in his education, and he was influenced by a physicist neighbor.[4] It was observed that Shockley's mental disorders may have derived from his parent's being strongly paranoid.[5] Shockley was granted a Ph.D. from MIT for a dissertation entitled, "Calculation of Electron Wave Functions in Sodium Chloride Crystals."[4] Shockley left Bell Labs in 1956 to found the Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory in in Mountain View, California, near Stanford University. At the end of that same year, Shockley shared the 1956 Nobel Prize in Physics with Bardeen and Brattain "for their researches on semiconductors and their discovery of the transistor effect." Shockley's management style eventually caused eight of his employees, known as the traitorous eight, to leave in 1957 and found Fairchild Semiconductor to produce inexpensive silicon transistors.

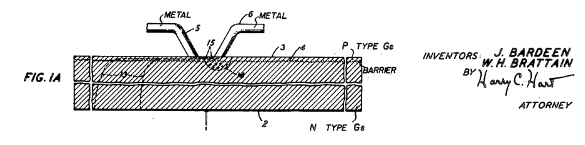

Figure 1A from US Patent no. 2,524,035, 'Three-electrode circuit element utilizing semiconductive materials,' by John Bardeen and Walter Brattain, October 3, 1950.[6] Shockley is not listed as an Inventor. (Via Google Patents.[4])

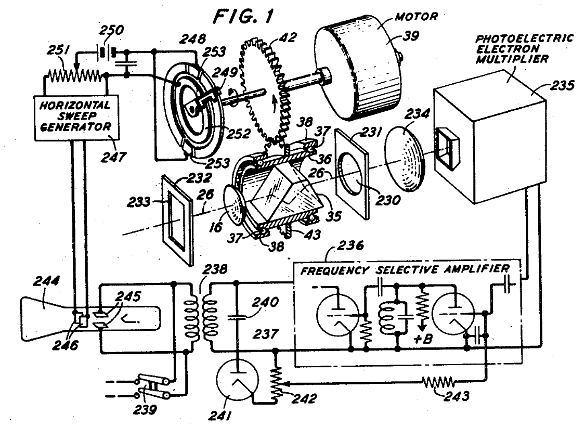

Shockley was good at physics, despite his personal failings.[7-9] The Shockley partial dislocation, a dislocation that's important since it's easily able to glide along fault planes, is named after him. He discovered this type of dislocation in 1947. In 1950, Shockley published his major work, the book, Electrons and Holes in Semiconductors (1950). One possible organizing principle in Shockley's career can be found in a 2013 article by David C. Brock in IEEE Spectrum.[10] Much of the science that Shockley pursued was motivated by a desire to replace both domestic workers and factory workers with a robotic workforce.[10] Brock makes the case that it all started with a patent application for an image sensor filed on March 19, 1948, at about the same time as the invention of the transistor.[10] This invention compared a visual scene with images on a roll of photographs to derive a control signal.[11] One application was for a guided bomb, but the device could be used for such things as facial recognition and component inspection.[11]

Figure 1 from US Patent no. 2,884,540, "Radiant energy control system," by William Shockley, April 28, 1959. As one whose history parallels that of transistor technology, it's interesting to see illustrations of the various mechanical and vacuum tube elements that were needed to accomplish things 70 years ago. (Via Google Patents.[11] Click for larger image.)

Shockley convinced Bell Labs to let him retain the intellectual property to improvements on this invention. Eventually, he tried to convince Mervin Kelly (1895-1971), president of Bell Labs and a physicist himself, to start research in using his "optoelectronic eye" to kick-start robot development, but Kelly wasn't interested. His robot eye patent was granted in December 1954 (but held secret until 1959).[11] Early in 1955, he was invited to an event honoring him, and also Lee de Forest (1873-1961), inventor of the triode vacuum tube.[10] At this event, Shockley met Arnold Beckman (1900-2004).[10] Beckman was a Ph.D. chemist who invented a commercially successful pH meter and a high-precision potentiometer, the Helipot.[10] Beckman had also worked at Bell Labs, where he acquired the electronics skill needed for his pH meter.[10] Beckman was also an advocate of automation, and in 1955 he funded the foundation of Shockley Semiconductor Lab as a part of Beckman Instruments for the manufacture of diffused silicon transistors.[10] Physicist, Frederick Seitz (1911-2008), who was the 17th president of the National Academy of Sciences from 1962-1969, and an acquaintance of Shockley during his student days, said this about Shockley:

"[Shockley] was unable to place himself in the shoes of others and thereby understand that advocating strong eugenic measures in a highly diverse society is bound to be highly disruptive. Yet he advocated that such a course be followed to the very end of his life... He was inclined to believe that society should be governed by what one might regard as an intellectually elite group... rather than by majority decisions as in a democratic society."[4]

References:

- Sylvia Nasar, "A Beautiful Mind," Simon & Schuster, July 12, 2011, 464 pp., ISBN: 978-1451628425 (via Amazon).

- Graham Farmelo, "The Strangest Man: The Hidden Life of Paul Dirac," Basic Books, June 28, 2011, 560 pp., ISBN: 978-0465022106 (via Amazon).

- Richard P. Feynman and Ralph Leighton, "Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman!": Adventures of a Curious Character," W. W. Norton & Company, February 6, 2018, 400 pp., ISBN: 978-0393355628 (via Amazon).

- John L. Moll, "William Bradford Shockley 1910—1989, A Biographical Memoir. National Academies Press, (Washington D.C.: 1995).

- Christophe Lécuyer, "Review of Broken Genius: The Rise and Fall of William Shockley, Creator of the Electronic Age," Physics Today, vol. 60, no. 2 (February 1, 2007, pp. 64f.), https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2711641.

- John Bardeen and Walter H Brattain, "Three-electrode circuit element utilizing semiconductive materials," US Patent no. 2,524,035, October 3, 1950.

- Joel N. Shurkin, "Broken Genius: The Rise and Fall of William Shockley, Creator of the Electronic Age," Palgrave Macmillan, June 13, 2006, 297 pp., ISBN: 978-0230551923 (via Amazon).

- William B. Shockley Biographical, Nobel Prize Foundation, 1956.

- Lillian Hoddeson, Interview of William Shockley at Murray Hill, New Jersey, September 10, 1974, AIP Oral Histories.

- David C. Brock, "How William Shockley’s Robot Dream Helped Launch Silicon Valley," IEEE Spectrum, November 29, 2013.

- William Shockley, "Radiant energy control system," US Patent no. 2,884,540, April 28, 1959.