Martian Moon Phobos

July 27, 2020 The planets visible with the unaided eye are still known today by the names of mythological deities given them in antiquity. Astronomers have kept this tradition in a similar naming of planets discovered telescopically after that time, as shown in the table. Pluto was demoted from full planet status in 2006, after many similar dwarf planets were discovered. I've included it in the table, since it was a planet from 1930 until that year.| Name | Namesake |

|---|---|

| Mercury | Mercury was the messenger of the Roman gods, and also the guide of souls to the underworld. |

| Venus | Venus is the Roman goddess of beauty, love, and desire. |

| Mars | Mars was the Roman god of war. The adjective, martial, derives from his name. |

| Jupiter | Jupiter is the king of the Roman gods, and also the god of the sky and thunder. He is often depicted clutching lightning bolts. |

| Saturn | The Roman god, Saturn, was the father of Jupiter, Neptune, and Pluto. |

| Uranus | The Greek god, Uranus, was the father of Saturn and was at one time the king of the gods. |

| Neptune | Neptune was the the Roman god of the sea. |

| Pluto | Pluto was the Roman god of the underworld. |

| Name | Namesake |

|---|---|

| Ceres | Ceres was the Roman goddess of agriculture and grain crops, whence we get the word cereal. |

| Vesta | Vesta was the Roman virgin goddess of the hearth, home, and family, whose temple was maintained by the Vestal Virgins. |

| Pallas | Pallas Athena was an alternate name for the Greek goddess Athena, the goddess of wisdom and handicraft, but also warfare. |

| Hygiea | Hygieia was the Greek goddess of health, from whom we get the word hygiene. |

| Name | Namesake |

|---|---|

| Io | Io was one of the mortal lovers of Zeus and an ancestor of Perseus. |

| Europa | Europa was a mortal woman who was abducted by Zeus, who took the form of a bull on that occasion. |

| Ganymede | Ganymede, who was described by Homer as the most beautiful of mortals, was abducted by Zeus in the form of an eagle, so he could become cup-bearer for the Olympic gods. |

| Callisto | Callisto was a nymph who was raped by Zeus. I enjoyed the Callisto character, portrayed by Hudson Leick, in Xena: Warrior Princess. |

| Metis | Metis was a Titaness and the first wife of Zeus. |

| Adrastea | Adrastea was a nymph who was the secret caregiver for the infant Zeus, who was in danger from his father, Cronus. |

| Amalthea | Amalthea was a goat herding nymph who likewise nurtured the infant Zeus. |

| Thebe | Thebe was another consort of Zeus. As you can see, Zeus had quite a sex drive. |

Our tradition of naming Solar System bodies after mythological beings was nearly defeated by Galileo (1564-1642), who discovered the first four moons of Jupiter using the recently invented telescope. In order to secure funding from the de' Medici family, he named these moons the "Medician Stars" in his book, Sidereus Nuncius ("Starry Messenger"), published March, 1610, less than two months after his discovery.

Fortunately, Simon Marius, who discovered the moons independently at about the same time as Galileo, gave them our now common names in 1614 at the suggestion of Johannes Kepler (1571-1630).

(A composite image of the Galilean moons, Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Io and Ganymede were imaged by NASA's Galileo spacecraft in June, 1996, while Europa and Callisto were imaged somewhat later. NASA/JPL/DLR image via Wikimedia Commons.)

Exploratory spacecraft have revealed that Saturn has many more moons than Jupiter, seven of which have names derived from Greek and Roman mythology.

| Name | Namesake |

|---|---|

| Mimas | Mimas was one of the Giants in Greek mythology. |

| Enceladus | Enceladus was another Giant. |

| Tethys | Tethys was the Titaness daughter of Uranus and Gaia, sister and wife of the Titan, Oceanus, and mother of the river gods and the Oceanids. |

| Dione | Dione is usually identified as the mother of Aphrodite (Venus). |

| Rhea | Rhea was the Titaness daughter of Gaia and Uranus. She is also the older sister and wife of Cronus, and is often called the mother of gods. |

| Titan | The Titans were descendants of Gaia and Uranus. |

| Iapetus | Iapetus was the Titan father of Atlas and Prometheus. |

A sculpture of the Greek god of the sea, Poseidon (Neptune in Roman mythology), at the Port of Copenhagen.

The word "trident" comes from the combination of Latin words for "three" and "teeth," as in the weapon in this sculpture. Homer's Iliad, however, uses the word τρíαινα for this, a word that just means "threefold." However, in the context, this type of fishing spear must have been implied.

(Photo by Hans Andersen, via Wikimedia Commons.)

| Name | Namesake |

|---|---|

| Naiad | The Naiads were nymphs who presiding over springs, brooks and other fresh water bodies. |

| Thalassa | Thalassa was a sea goddess |

| Despina | The nymph, Despoina, was a daughter of the ocean god, Poseidon |

| Galatea | Galatea was a Nereid. Her name translates as she who is milk-white |

| Larissa | Larissa was a nymph lover of the sea god, Poseidon, who fathered three sons by her |

| Hippocamp | The Hippocamp is a chimera that's half horse and half fish |

| Proteus | Proteus was a prophetic sea god who changed his shape to avoid capture. His name gives rise to the adjective, protean |

| Triton | Triton was a son of Poseidon, and he was represented as a merman who blew a conch shell like a trumpet |

| Nereid | The Nereids were sea-nymph attendants to Poseidon |

| Halimede | Halimede was one of the many Nereids |

| Sao | Sao was a Nereid associated with sailing |

| Laomedeia | Laomedeia was another Nereid |

| Psamathe | The Nereid, Psamathe, was the goddess of sand beaches and wife of Proteus |

| Neso | Neso was another Nereid |

| Name | Namesake |

|---|---|

| Charon | Charon was the ferryman who brought the dead across the river, Styx |

| Styx | Styx was the goddess associated with the river, Styx |

| Nix | Nyx was the goddess of darkness and night and the mother of Charon |

| Kerberos | Kerberos is the Greek name for Cerberus, the three-headed dog that guards the gates of the Underworld |

| Hydra | The Lernaean Hydra was the nine-headed serpent guard of Lerna, an entrance to the Underworld |

A color image of Phobos, imaged by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, March 23, 2008. Stickney crater, with a diameter of 9 kilometers (5.6 miles), can be seen at the lower right.

(NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona image via Wikimedia Commons. Click for larger image.)

Christopher Edwards, an assistant professor in the Department of Astronomy and Planetary Science of Northern Arizona University, and scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Arizona State University, performed a recent thermal imaging study of Phobos to help determine whether Phobos is a captured asteroid, or a fragment of Mars that was ejected by impact of a meteorite.[2] They used the Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS) of the Mars Odyssey orbiter to capture the images during the moon's different phases.[2] The Mars Odyssey orbiter has been observing Mars for more than 18 years.[2] These images are a marked improvement over previous studies.[3]

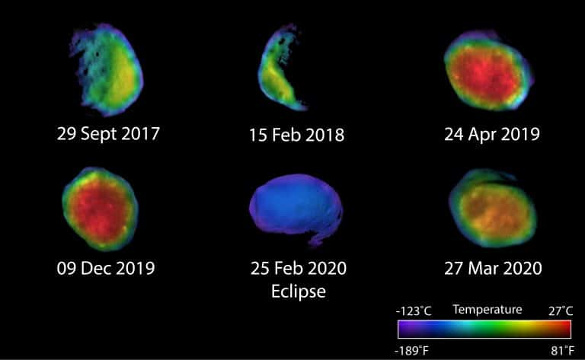

Thermal images of Phobos during its different phases, waxing, waning and full. These include a December 9, 2019, image of Phobos at its maximum temperature (27 degrees Celsius), an image of February 25, 2020, in which Mars' shadow completely blocked sunlight from its surface (-123 degrees Celsius), and a March 27, 2020, image where Phobos was exiting an eclipse and just warming.[2]. (NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASU/NAU image from Northern Arizona University (NAU), also available here)

The thermal imaging revealed that the surface of Phobos is relatively uniform and composed of very fine-grained, mostly basaltic, materials.[2] While these images don't provide a definitive answer to the question of Phobos' origin, they're an important piece of evidence. The Japanese Space Agency (JAXA) has planned a Martian Moons Exploration (MMX) mission to Phobos and Diemos. MMX will land and collect samples from Phobos, and the thermal imaging study has provided reconnaissance data for that mission.[2]

References:

- Elizabeth Zubritsky, "Mars' Moon Phobos is Slowly Falling Apart," NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center Press Release, November 10, 2015.

- NAU planetary scientist captures new images of Martian moon Phobos to help determine its origins, Northern Arizona University Press Release, June 3, 2020.

- Martian Moon Phobos in Thermal Infrared Images, NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory Website, October 4, 2017.