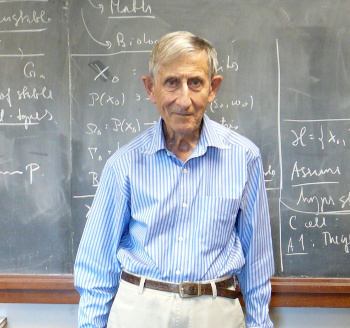

Freeman Dyson (1923-2020)

April 20, 2020 Mathematics is an important part of physics, and those who are extraordinarily proficient in mathematics will become extraordinary physicists. Some ready example include, in no particular order, Isaac Newton, Albert Einstein, Carl Friedrich Gauss, Daniel Bernoulli, William Rowan Hamilton, John von Neumann, Enrico Fermi, Paul Dirac, and Stephen Hawking. Many of these, such as Einstein and Gauss, are known to have excelled in mathematics as young children. Another is Freeman Dyson, who died on February 28, 2020, at age 96.

Freeman Dyson (1923-2020) in 2007.

Various sources report that as a child he enjoyed reading Eric Temple Bell's, "Men of Mathematics" and was constantly doing calculations on paper as a young child.

He was interested in large numbers and he calculated the number of atoms in the Sun (My estimate, based on a Solar mass of about 2x1033 grams and the mass of an atom of hydrogen of 1.67x10-24 grams, is 1.2x1057).

Dyson was admitted to Trinity college, Cambridge, UK, on a scholarship at age 15, and at age 17 he studied mathematics with number theorist, G. H. Hardy.

(Wikimedia Commons photograph by Monroem. Click for larger image.)

Dyson entered his professional career just after World War II, which was an exciting time for physics. He came to the United States in 1947 as a Commonwealth Fellow to study at Cornell University (Ithaca, New York) under Hans Bethe for a physics Ph.D., never completed. While at Cornell, he met Richard Feynman (1918-1988), who had joined the Cornell faculty in 1945 after his exit from the Manhattan Project. Dyson recalled in an interview a four day road trip that he made with Feynman from Cleveland, Ohio, to Albuquerque, New Mexico.[1] As something one would expect from a Feynman road trip, the duo spent a night in a 50-cent room in an Oklahoma brothel as shelter from a heavy rain.[1] Dyson remarked also on Feynman's cavalier approach to mathematical physics.

"So what I was always trying to persuade Feynman was that it's not enough to get the right answers, you have to understand what you're doing. And so we had big arguments about that, and I told him that he ought to learn some quantum field theory if he wanted really to understand this, and he said it just was a language he never would learn and he didn't think it was worth it. As far as he was concerned he thought in pictures and he didn't think in terms of equations. I thought in terms of equations and not in pictures. So we never agreed, but we just had fun talking."[1]Dyson spent about a year from 1948-1949 at the Institute for Advanced Study, after which he returned to England for a short time as a research fellow at the University of Birmingham. A major problem in physics at that time was how to reconcile electromagnetism and quantum mechanics to create quantum electrodynamics (QED), a complete description of how light and matter matter. Dyson's first-hand experience with Feynman and Julian Schwinger (1918-1994) allowed him to show the equivalence between Feynman's version of QED, based on his eponymous Feynman diagrams, and Schwinger's more traditional operator approach, shared by Japanese physicist, Sin-Itiro Tomonaga (1906-1979), in a 1949 paper.[2] Dyson refined and popularized Feynman's approach, and Schwinger, Feynman and Tomonaga shared the 1965 Nobel Prize in Physics "for their fundamental work in quantum electrodynamics (QED), with deep-ploughing consequences for the physics of elementary particles."[3] Dyson's reward for his effort was a lifetime appointment at the Institute for Advanced study, arranged by its director, J. Robert Oppenheimer, at the recommendation of Hans Bethe. Oppenheimer had been skeptical of Feynman's approach, but he hired Dyson for proving he was wrong. Dyson became a US citizen in 1957, and he remained a member of the Institute until his death. As for his not getting a share of the Nobel Prize, Dyson said, "I was not inventing new physics... I merely clarified what was already there so that others could see the larger picture."[4]

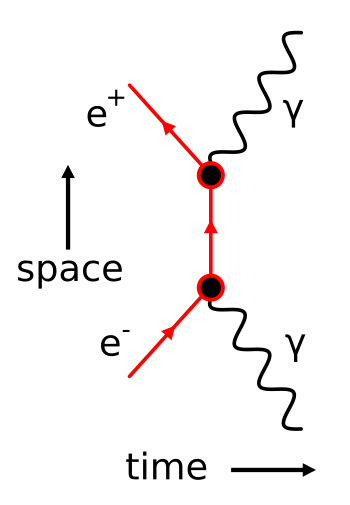

Feynman diagram of electron-positron annihilation.

The interaction of an electron (e-) and positron (e+) can be elastic, in which case they bounce off each other; or, they can interact and destroy each other in a matter-antimatter annihilation that produces gamma rays (γ).

The nuclear reaction is (e-) + (e+) -> γ + γ.

(Wikimedia Commons image, modified using Inkscape. Click for larger image.)

References:

- Interview with Freeman Dyson, Scientist, at the Web of Stories.

- F. J. Dyson, "The Radiation Theories of Tomonaga, Schwinger, and Feynman," Physical Review Letters, vol. 75, no. 3 (February 1, 1949), pp. 486ff. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.75.486. A free PDF file download is available at this link.

- The Nobel Prize in Physics 1965, The Nobel Foundation website.

- Tim Radford, "Freeman Dyson obituary," The Guardian (UK), March 1, 2020.

- CODATA Internationally recommended 2018 values of the fundamental physical constants, NIST Standard Reference Database 121. Also of interest are a wall chart and wallet card of the constants, both as PDF files.

- Andrea Stone, "Freeman Dyson, legendary theoretical physicist, dies at 96," National Geographic, February 28, 2020.

- Justin Stabley, "Pioneering theoretical physicist Freeman Dyson dies at 96," PBS News Hour, February 28, 2020.

- Katyanna Quach, "RIP Freeman Dyson: Science's civil rebel dies aged 96," The Register (UK), February 28, 2020.

- Freeman Dyson's Interview (Princeton, New Jersey, February 18, 2015), YouTube Video by Manhattan Project Voices, March 26, 2008. A transcript is available here.