Optical Ruler

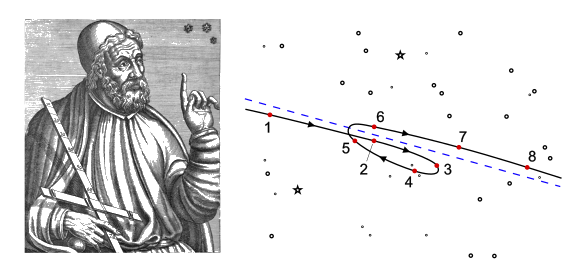

August 5, 2019 I once read a parody about how science is usually done. It imagined how scientific papers would have been written in the age of Ptolemaic astronomy; that is, the cosmological model that had Earth as the center of the Solar System. Since planets sometimes move in retrograde fashion, and not in a uniform circular orbit around the Earth, Alexandrian astronomer, Ptolemy (c.100-c.170), proposed an explanation. In his Almagest, Ptolemy explained that the planets spun on additional spheres attached to their primary orbital sphere centered on Earth, creating epicycles. While one additional sphere explained most of the retrograde motion, this single epicycle still left some motions unexplained. In a solution that would appall William of Ockham (c. 1287–1347), it was proposed that the planets are carried by a third sphere carried on this second sphere. In the parody, more refined measurements would require further spheres, and we would get papers entitled, "A nine epicycle fit to the orbit of Mars." The proper solution to the problem of retrograde motion was the heliocentric Copernican system.

Ptolemy (c.100-c.170) and the retrograde motion of Mars. The position of Mars is shown for monthly intervals with the ecliptic marked by the dashed blue line. (Ptolemy image from Les vrais pourtraits et vies des hommes illustres grecz, latins..., Blanche Marantin and Guillaume Chaudiere Publishers (Paris, 1584), via Wikimedia Commons. Apparent retrograde motion figure by M.L. Watts, taken from data in Thomas S. Kuhn, La rivoluzione copernicana (The Copernican Revolution), (Einaudi, Torino:2000), p. 63., via Wikimedia Commons (modified). Click for larger image.)

This example illustrates how measurement is an important part of science. Accurate measurements of planetary motion demonstrated how a once popular scientific model lacked predictive accuracy, and this led to the Copernican Revolution. While astronomers at those times could measure motions in reference to the fixed stars, motion in the laboratory is measured with a ruler, and this ruler can take forms quite different from marks on a wooden or metal slat. Lengths are measured in relation to some length reference. In the past, when measurements were not that critical, the reference was as crude as a the cubit, the length of a person's forearm, and the barleycorn, the length of which was supposed to be a third of an inch. At the end of the 18th century, the meter was defined as one ten-millionth of the distance from the equator to the North Pole, which makes for an unwieldy calibration unit. The meter was re-defined in 1799 as the length of a physical object, the prototype meter, a cylinder of platinum-iridium alloy, maintained at the Bureau International des Poids et Mesures (International Bureau of Weights and Measures) outside Paris. As science progressed, so did the accuracy of the meter. In 1960, it was redefined as equal to 1,650,763.73 wavelengths of the orange-red emission line of krypton-86. In 1983, the length of the meter was redefined as the length of the path traveled by light in vacuum during a time interval of 1/299792458 of a second. This redefinition was possible, since the speed of light in vacuum was fixed at exactly 299,792,458 meters per second; or, as I use it in most calculations, 300,000,000 meters per second. Marks on a meter stick are useful for length measurement in most laboratories and machine shops, but astronomers needed to work for years to establish distance measurement to stars, galaxies, and other objects of cosmological significance. Measurement of the distance to objects as distant as 13 billion light years has been enabled by Hubble's law and the redshift caused by the expansion of the universe.

Left, Edwin Hubble (1889-1953) in a 1931 portrait by Johan Hagemeyer (1884-1962); and, right, a photograph of the Hubble Space Telescope named after him. While Hubble didn't discover universal expansion, he did quantify the expansion in Hubble's law. In particular, American astronomer, Vesto Slipher (1875-1969), noticed high galactic redshifts a decade before publication of Hubble's Law. (Left image (modified) and right image via Wikimedia Commons. Click for larger image.)

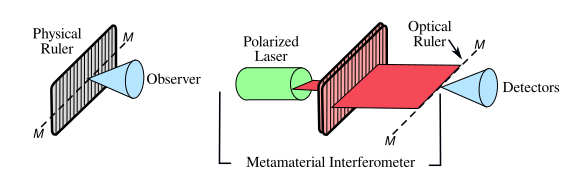

At the opposite side of the length scale, in the realm of nanotechnology, our ability to measure is constrained by our ability to see, and the wavelength λ of radiation imposes a limit to sight. Resolving power is typically limited to about half the wavelength of the radiation. That's why X-rays with tenth nanometer wavelength are used in X-ray diffraction of crystals in which the atomic spacing is of the order of a nanometer. Scientists at Nanyang Technological University (Singapore, Singapore), and the University of Southampton (Southampton, UK) have transcended this wavelength limit by developing an optical ruler operating at 800 nm wavelength with a resolution of λ/800. Their technique, as shown below, will theoretically allow resolving powers of about λ/4000. It uses a metamaterial as a way to produce a spatially changing phase front that forms an interference pattern.[1]

Schematic diagrams of a conventional ruler and a metamaterial optical ruler. A conventional ruler is read by observing the radiation (e.g., light) reflected from the ruler. In the metamaterial optical ruler, light from a polarized laser is passed through a metamaterial to create deep subwavelength zones of a complex optical field with a strong phase gradient along the M-M line. The wavelength of the laser used in these experiments was 800 nm, and the laser beam is arranged to interfere with the light passed through the metamaterial to create deep fringes.[1] (Created using Inkscape. Click for larger image.)

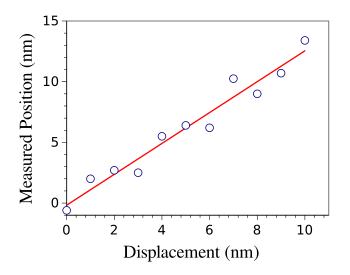

The optical ruler is an electromagnetic analog of a physical ruler in which a complex electromagnetic field produces singularities that act as ruler markings.[1] Multiple refractions of light on the surface of a Pancharatnam-Berry phase metamaterial allows the creation of an interference pattern when combined with the incident light, and this produces strong interference fringes.[1] The ruler is read by an image sensor with a pixel size of 6.5 μm through a 1300X magnification lens.[1] In the demonstration data shown in the graph, the resolving power of about 1 nm was limited by the positioning accuracy of the piezoelectric actuator and the resolution of the image sensor.[1]

Optical ruler measured position as a function of 1 nanometer displacements of a piezoelectric actuator.

The standard deviation of the measurement is 960 picometers.

(Graphed using Gnumeric from data in fig. 3B of ref. 1.)[1]

The metamaterial can be created on the tip of an optical fiber to facilitate displacement sensing.[1] Such a ruler with dimensions of just a few micrometers will facilitate applications in nanometrology, nanolithography, and nanosensing.[1] Such an optical ruler can be used in combination with a nanoindenter to allow measurement of the mechanical properties of nanomaterials.[1]