Scientific Broadness

September 30, 2019 The best commentary about scientists comes from scientists themselves. American chemist, Robert E. Swain (1875-1961) was head of the Stanford University chemistry department from 1917-1940, and he was also a mayor of Palo Alto, California and a founder of SRI International. As reported on the notably authoritative website, quoteinvestigator.com, Swain explained the difference between a scientist and a philosopher as follows:"Some people regard the former as one who knows a great deal about a very little, and who keeps on knowing more and more about less and less until he knows everything about nothing. Then he is a scientist... Then there are the latter specimen, who knows a little about very much, and he continues to know less and less about more and more until he knows nothing about everything. Then he is a philosopher."[1]There's obvious criticism of either approach. Many scientists attempt to spend their entire career researching the same narrow topic that earned them their postgraduate degree. The allure in this is great, since their expertise is already established, and it's easy to continue from there. Today's science, however, moves at a rapid pace, and it's likely that their previously important niche will fade from significance. I experienced this myself when one of my first scientific interests, magnetic bubble materials, became a mere footnote in the history of computer memory within just a decade.

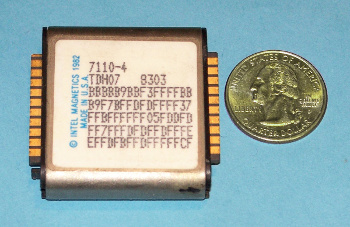

Intel Magnetics magnetic bubble memory module (c. 1982).

The US quarter dollar coin has a diameter of almost exactly one inch (24.26 millimeter, 0.955 inch).

(Wikimedia Commons image by the author.)

Fortunately, I had fallen sideways into magnetic bubble materials, having done previous work in the associated fields of the rare earth elements and magnetism, so this research was a detour rather than a destination. Additionally, my withdrawal was aided by a developing interest in optics that was inspired by my laser-blasting colleagues, and my extracurricular interests in computers and electronics. It quickly became obvious to me that a broad background in science was essential for survival in a corporate research laboratory, where research projects have very short lifespans. While a scientist might plan his education around several disparate topics that appear to be useful in composite, the connections that an interdisciplinary mind will make are mostly random; and, it's the most random of these that often are the most useful. Around the time that I started my involvement in magnetic bubbles, science historian, James Burke (b. 1936), presented his television documentary series Connections on PBS, followed by a series of similarly titled articles in Scientific American from 1996-2001. While the history of science is usually presented in a linear-logical fashion, Burke's thesis is that the very useful things of today's world evolved from a connected progression of events with no logical plan. The series is interesting because of its confusion. A jumble of things is found to have led to some important idea or invention. The idea of how broad knowledge can lead to some interesting connections was explored by Sabine Hossenfelder in an article entitled, Automated Discovery, in her always interesting Backreaction Blog.[2] She presents a 1986 paper that revealed a simple syllogism that was buried in the scientific literature. Dan Swanson of the The University of Chicago saw one set of articles that showed how certain types of fish oils aided circulatory health, and another set that showed that improved circulatory health aided patients with Raynaud syndrome.[3] Swanson made the connection that fish oil would benefit Raynaud syndrome patients, and this was proved correct in a 1993 clinical trial.[2]

A scientist with broad knowledge; or, just a broad scientist?

In my experience, few scientists are obese, and there's a proven correlation between obesity and education level.

A recent paper on the topic concludes that higher body mass results in less education, rather than less education leading to higher body mass.

(Wikimedia Commons image, modified for artistic effect, Photo no. L0020234, library file ICV No 7381, an 1806 etching by C. Williams, from Wellcome Images by the Wellcome Trust.)

While such a connection seems obvious, the evidence was buried in two disparate mounds of scientific literature, so it wasn't noticed. That was in the 1980s, just at the start of ubiquitous computing and the Internet. Such data mining is far easier today, and discovery of such connections can be automated through use of artificial intelligence agents. Hossenfelder cites as an example research by scientists from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley, California) and the University of California (Berkeley, California) in a recently published article in Nature.[3] The California research team looked at connections between published papers in my field of materials science. While previous studies looked for connections using keyword databases, the team used all the words in the paper abstract, a technique that's much more computationally intensive.[2-3] They've released their Word2vec computer codes on github.[4] Word2vec was developed at Google, and I wrote about Word2vec research in 2017 on another materials topic in an earlier article (Data Mining for Material Synthesis, February 19, 2018). In the 2017 study, a team of materials scientists and computer scientists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT, Cambridge, Massachusetts), the University of Massachusetts Amherst (Amherst, Massachusetts), and the University of California Berkeley (Berkeley, California) data mined more than twelve thousand research papers to automatically deduce recipes for producing materials.[6-7] The team used data mining to find hydrothermal synthesis recipes for titania nanotubes. They found that it was possible to identify paragraphs that contained recipes with 99% accuracy.[7] As an example that a full text indexing is superior to just indexing a paper's abstract, the California research team found that materials mentioned in the text body near the word thermoelectric were not mentioned together in the abstract.[2] They demonstrated through use of historical data that their computer system could recommend materials for functional applications several years before their actual discovery.[3] They predicted that fifty materials would be thermoelectric and found that these materials were about eight times more likely to be checked as thermoelectrics than randomly chosen unstudied materials.[2] Tom Prince from North Carolina State University, and Hossenfelder have posted an article on arXiv that attempts to measure scientific broadness.[7] Not only is their article posted on arXiv, but their analysis was on papers posted on arXiv. To examine a scientist's broadness, they removed all papers with more than 30 authors, since such huge collaborations were presumed to follow a different probability distribution, and they also ignore authors with fewer than 20 papers, since so few publications makes broadness difficult to detect. The final sample contains 46,772 authors and 1,350,611 papers.[7] Price and Hossenfelder developed a model for scientific broadness of arXiv authors based on article posting across subject areas. This approach is validated by the distribution of their broadness measure among the scientist sample (see figure). They found that the broadest interests were held by individuals in plasma physics, statistical mechanics, and the mathematical areas of numerical analysis, probability, and mathematical physics. The least broad (narrow-minded?) were in astrophysics of galaxies, and algebraic geometry.[7]

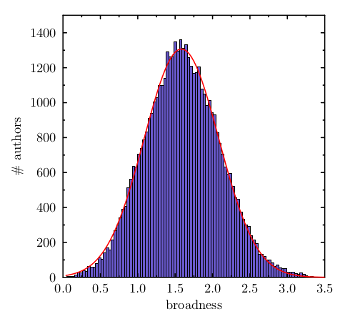

Probability distribution of broadness in the sample of arXiv authors.

The distribution is very close to a normal distribution, which is what would be expected if the definition of broadness was valid.

(Fig. 1 of ref. 8, via arXiv.[8])

More interesting is the broadness ranking of scientists by country, as shown in the table. Scientists from the United States and Japan appear to lag behind those of countries such as Israel, China, and The Netherlands, although the difference in broadness is not that large.[7] Table: Mean broadness by country.

| Country | Mean | | | Country | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Israel | 1.745 | | | Brazil | 1.590 |

| Austria | 1.705 | | | Switzerland | 1.590 |

| China | 1.639 | | | Germany | 1.583 |

| France | 1.634 | | | United States | 1.578 |

| The Netherlands | 1.624 | | | Canada | 1.570 |

| India | 1.619 | | | UK/N. Ireland | 1.568 |

| Belgium | 1.610 | | | Sweden | 1.560 |

| Hungary | 1.609 | | | Spain | 1.556 |

| Italy | 1.600 | | | Japan | 1.482 |

| Australia | 1.599 | | | Iran | 1.430 |

| Poland | 1.595 | | | South Korea | 1.404 |

| Russian Federation | 1.593 | | |

References:

- Knows Much About Little: That Is One Definition Given of Scientist By Chemist, 1928 April 7, The Ogden Standard-Examiner (Ogden, Utah), p 1, col. 4.

- Sabine Hossenfelder, Automated Discovery, Backreaction Blog, August 1, 2019.

- D.R. Swanson, "Fish oil, Raynaud's syndrome, and undiscovered public knowledge," Perspect. Biol. Med., vol. 30, no. 1 (Autumn, 1986), pp. 7-18.

- Vahe Tshitoyan,, John Dagdelen, Leigh Weston, Alexander Dunn, Ziqin Rong, Olga Kononova, Kristin A. Persson, Gerbrand Ceder, and Anubhav Jain, "Unsupervised word embeddings capture latent knowledge from materials science literature," Nature, v. 571, no.7763 (July 3, 2019), pp. 95–98.

- Supplementary Materials for Tshitoyan et al. "Unsupervised word embeddings capture latent knowledge from materials science literature", Nature (2019).

- Edward Kim, Kevin Huang, Adam Saunders, Andrew McCallum, Gerbrand Ceder, and Elsa Olivetti, "Materials Synthesis Insights from Scientific Literature via Text Extraction and Machine Learning," Chem. Mater. (Article ASAP, October 19, 2017), DOI: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b03500.

- Larry Hardesty, "Artificial intelligence aids materials fabrication," MIT Press Release, November 5, 2017.

- Tom Price and Sabine Hossenfelder, "Measuring Scientific Broadness," arXiv, August 3, 2019.