The Zwicky Transient Facility

April 15, 2019 Astronomy is a subfield of physics. Since physics also concerns itself with the quantum realm, the purview of physics extends over 61 orders of magnitude from the diameter of the universe (8.8 x 1026 m) to the Planck length (1.616 x10-35 m). That's a lotta yotta! The first Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded in 1901 to Wilhelm Röntgen (1845-1923) "in recognition of the extraordinary services he has rendered by the discovery of the remarkable rays subsequently named after him."[1] Röntgen rays sound like something from a Flash Gordon serial. We now call such rays x-rays. The Nobel Physics Prize wasn't awarded in astronomy until 35 years later, and the second wasn't awarded until 31 years after the first.[1] As can be seen from the table, below, astronomy Nobel Prizes became much more frequent after 1970. This was a consequence of improved instrumentation, with radio astronomy born from World War II radar technology and satellite observatories enabled by the "space race."| Year | Award |

|---|---|

| 1936 | Victor Hess "for his discovery of cosmic radiation." |

| 1967 | Hans Bethe "for his contributions to the theory of nuclear reactions, especially his discoveries concerning the energy production in stars." |

| 1974 | Sir Martin Ryle and Antony Hewish "for their pioneering research in radio astrophysics: Ryle for his observations and inventions, in particular of the aperture synthesis technique, and Hewish for his decisive role in the discovery of pulsars." |

| 1978 | Arno A. Penzias and Robert W. Wilson "for their discovery of cosmic microwave background radiation." |

| 1983 | Subramanyan Chandrasekhar "for his theoretical studies of the physical processes of importance to the structure and evolution of the stars," and William A. Fowler "for his theoretical and experimental studies of the nuclear reactions of importance in the formation of the chemical elements in the universe." |

| 1993 | Russell A. Hulse and Joseph H. Taylor Jr. "for the discovery of a new type of pulsar, a discovery that has opened up new possibilities for the study of gravitation."[2] |

| 2002 | Raymond Davis Jr. and Masatoshi Koshiba "for pioneering contributions to astrophysics, in particular for the detection of cosmic neutrinos," and Riccardo Giacconi "for pioneering contributions to astrophysics, which have led to the discovery of cosmic X-ray sources." |

| 2006 | John C. Mather and George F. Smoot "for their discovery of the blackbody form and anisotropy of the cosmic microwave background radiation." |

| 2011 | Saul Perlmutter, Brian P. Schmidt and Adam G. Riess "for the discovery of the accelerating expansion of the Universe through observations of distant supernovae." |

Astronomer, Fritz Zwicky, examining a photographic plate.

Zwicky characterized himself as a "lone wolf" who preferred to do most work himself.

The asteroid, 1803 Zwicky, and the lunar crater, Zwicky, are both named in his honor.

(Still image from a Caltech YouTube Video, modified for artistic effect.[4])

Zwicky had interests beyond astronomy, researching jet engine designs for the Aerojet Engineering Corporation from 1943 through 1961. He was listed as an inventor on more than fifty patents, many of which involve jet propulsion, but his main career interest was supernovae. In fact, he and Walter Baade (1893-1960) coined the term "supernova" in 1934. They hypothesized that supernovae happened when normal stars transformed into neutron stars, producing cosmic rays. Zwicky discovered more than a hundred supernovae himself in the era in which this task was accomplished by laborious examination of photographic plates, as in the above photo. One strange theory of Zwicky's was the idea of tired light. Although universal expansion was identified as the cause of the cosmological redshift, Zwicky in 1929 conjectured that photons would lose energy in their travels over long distances by interaction with particles, and this would cause the redshift. However, as Zwicky observed, such interactions would also blur the images of distant objects, and this blurring isn't seen. Today, there are many reasons to believe that the cosmological redshift is truly from universal expansion Zwicky became a professor of astronomy at Caltech in 1942, and he was a staff member at Mount Wilson Observatory and Palomar Observatory for most of his career. In 1972, shortly before his death, he was awarded the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society for "distinguished contributions to astronomy and cosmology." The Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF), a project located at Caltech's Palomar Observatory and designed to capture such things as supernovae, has been named in his honor. Since its inception in March, 2018, ZTF has discovered 50 small near-Earth asteroids and more than 1,100 supernovae, and it has also observed more than 1 billion stars in the Milky Way galaxy. One near-Earth asteroid that it discovered, 2019 AQ3, has an orbital period of just 165 days, the shortest for any asteroid.[4-5]

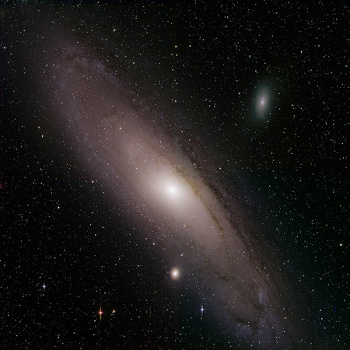

A view of neighbor galaxy, Andromeda, by the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF).

This image , just a sixteenth (2.9 square degrees) of ZTF's full field of view, is a composite image of three visible light ranges.

Andromeda is 2.5 million light-years distant.

(Caltech image by ZTF/D. Goldstein and R. Hurt.)

ZTF observations are through the 48-inch Samuel Oschin Telescope at Palomar, where it surveys the northern skies for transient events; that is, explosions, movement, or changes in object brightness.[5] It has a wide single-image observation field that's 240 times the size of the full moon.[5] It surveys the entire northern sky every three nights, and it discovers several supernovae each night.[5] There's an automated messaging system that automatically sends alerts to astronomers within 10-20 minutes when events are detected, and a program funded by the National Science Foundation called GROWTH that sends alerts to 18 international observatories in the northern hemisphere.[5] There can be hundreds or thousands of alerts per night.[5] Says Shrinivas Kulkarni, the principal investigator of ZTF and a professor of Astronomy and Planetary Sciences at Caltech,

"There's a lot of activity happening in our night skies... In fact, every second, somewhere in the universe, there's a supernova that's exploding. Of course, we can't see them all, but with ZTF we will see up to tens of thousands of explosive transients every year over the three-year lifetime of the project... It's a cornucopia of results... We are up and running and delivering data to the astronomical community. Astronomers are energized."[5]Aside from the January 4, 2019, discovery of asteroid 2019 AQ3, ZTF caught two other near-Earth asteroids, 2018 NX and 2018 NW. These made a close approach to Earth of less than 80,000 miles, which is about a third the distance between Earth and the Moon.[5] Thomas Prince, a ZTF co-investigator and a professor of physics at Caltech, has focused on the identification of potential gravitational wave sources, such as pairs of compact stars like white dwarfs, that might be detected by future space-based gravitational-wave detectors.[5] Says Prince,

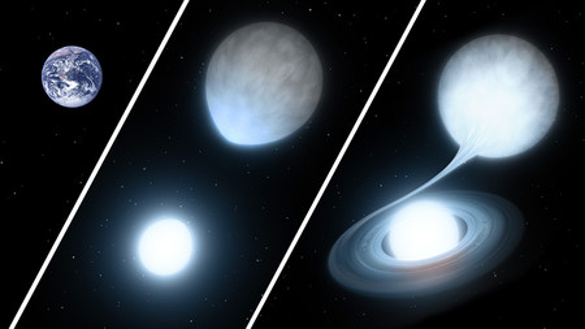

"Because we cover so much sky so often, we can find these rare exotic binary systems that contain two white dwarf stars, each about the size of Earth but about half the mass of our Sun. Their orbits are predicted to become smaller and smaller because of the loss of energy due to gravitational waves."[5]

An artist's impression of two white dwarfs orbiting around each other is shown in the middle panel, with the size of the Earth as a reference shown on the left. While the white dwarfs are comparable in size to the Earth, they are 200,000 times more dense, and a tidal bulge is seen on one of the stars. The panel on the right shows how one star of the pair can accrete material from the other. (Caltech image.[5])

ZTF is a smaller version of the 2022 Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST) which will have the ability to image an area of sky 13 times larger than that scanned by ZTF.[5] The development and operational cost of ZTF has been about $24 million, about half of which has come from the National Science Foundation with the rest coming from international partners, Caltech, and the Heising-Simons Foundation.[5] A plethora of ZTF papers was posted on arXiv at the beginning of February.[6-12]

References:

- The Nobel Prize - All Nobel Prizes in Physics, Nobel Prize Web Site.

- Taylor is also an avid radio amateur, having obtained his first amateur radio license as a teenager. This interest in radio inspired him to enter the field of radio astronomy. Taylor has a special interest in weak signal communication, and he organized an April, 2010, project that used the Arecibo Radio Telescope to bounce radio signals from the Moon to communicate with radio amateurs worldwide. He has a home page at the Princeton University Physics Website, the WSJT Home Page.

- F. Zwicky, "On the Masses of Nebulae and of Clusters of Nebulae," Astrophysical Journal, vol. 86, no. 3 (October, 1937), pp. 217-246, DOI:10.1086/143864. A PDF copy is available here.

- Zwicky Transient Facility Opens Its Eyes to the Volatile Cosmos, Caltech YouTube Video, November 14, 2017.

- Whitney Clavin, "Zwicky Transient Facility Nabs Supernovae, Stars, and More," Caltech Press Release, February 7, 2019.

- Eric C. Bellm, et al., "The Zwicky Transient Facility: System Overview, Performance, and First Results," arXiv, February 5, 2019.

- Matthew J. Graham, et al., "The Zwicky Transient Facility: Science Objectives," arXiv, February 5, 2019.

- Frank J. Masci, et al. "The Zwicky Transient Facility: Data Processing, Products, and Archive," arXiv, February 5, 2019.

- Ashish Mahabal, et al. "Machine Learning for the ZTF," arXiv, February 5, 2019.

- Maria T. Patterson, et al., "The Zwicky Transient Facility Alert Distribution System," arXiv, February 6, 2019.

- M. M. Kasliwal, et al., "The GROWTH Marshal: A Dynamic Science Portal for Time-domain Astronomy," arXiv, February 5, 2019.

- Yutaro Tachibana and A. A. Miller, "A Morphological Classification Model to Identify Unresolved PanSTARRS Sources: Application in the ZTF Real-Time Pipeline," arXiv, February 5, 2019.