Giovanni Battista Riccioli

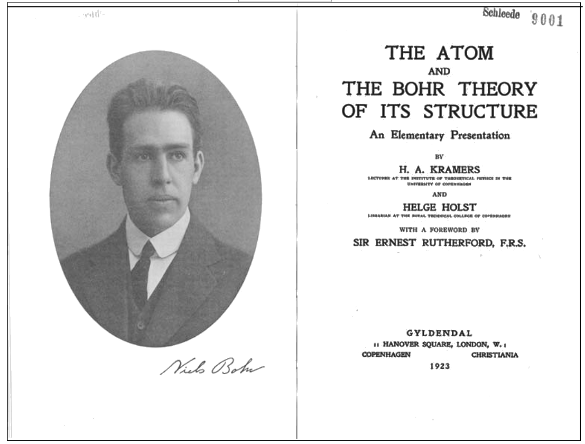

December 2, 2019 They say that "history is written by the victors," and this is true for the history of science. While the successful theories are presented in textbooks, their opposing theories are lost in the mists of time. The names of the winners, such as Copernicus and Einstein, become household words. These scientists become topics of hagiographies, while the proponents of the opposition theories are either forgotten or vilified. I wrote about one example of this in an earlier article (Bohr Model of the Atom, January 3, 2012) in which I summarized the arXiv paper, "Spreading the gospel: The Bohr atom popularized," by Helge Kragh and Kristian Hvidtfelt Nielsen.[1] This arXiv paper recalls the several models of the atom that appeared at the time of Bohr's atomic theory, and it also explains how Bohr's theory was popularized (see image).

Frontpiece of H. A. Kramers and H. Holst, 'The Atom and the Bohr Theory of its Structure,' (Gyldendal, London), 1923. This book, which helped to popularize Bohr's atomic model, was originally published in Danish in 1922, the same year that Bohr received the Nobel Prize in Physics.[1] It was subsequently translated and published in many languages, the English translation of which was done by a young Robert Bruce Lindsay (1900-1985) and his wife Rachel Tupper Lindsay.[1] Lindsay is known for his acoustics research, as well as his own physics popularizations. (Click for larger image.)

Chemists were most eager to develop an atomic theory, and American chemist, Gilbert N. Lewis (1875-1946), jumped into the fray with his 1902 cubic atom. This model had electrons positioned at the eight corners of a cube, and this explained atomic valency, since the elements in the first three rows of the periodic table have eight electrons (two s-electrons and six p-electrons) in their outer shell. Of course, the transition metals were hard to explain, and two decades later, quantum mechanics came along to explain the periodic table in detail. I wrote about Lewis in a previous article (Gilbert N. Lewis, November 16, 2011). Although Bohr prevailed, his 1913 atomic theory was on shaky ground at the start. It was just another contender and was only victorious a decade later after sufficient development of quantum mechanics. The principal problem with the Bohr planetary model was that its electrons are accelerating charges, and accelerating charges radiate energy. The electrons in orbit about a nucleus will lose energy and spiral into the nucleus. Quantum mechanics and the Bohr model would not have existed were it not for the Scientific Revolution, which occurred many centuries prior. While many scientific disciplines flourished after the Middle Ages, the greatest turning point in human thought was when Nicolas Copernicus (1473-1543) launched the Copernican Revolution that supplanted the geocentric model of the universe with a heliocentric model. Isaac Newton, in his 1687 Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, derived Kepler's laws of planetary motion from his gravitation equations as well as other phenomena that could only be explained by a heliocentric Solar System. At that point, heliocentrism was proved, but there was quite a gap between the 1543 publication of Copernicus' De revolutionibus orbium coelestium and Newton's Principia. In that period, heliocentrism was still questioned, and many of the best arguments against it were developed by Italian astronomer and Jesuit priest, Giovanni Battista Riccioli (1598-1671). Although geocentrism was later proven wrong, Riccioli's astronomical observations and physical experiments were significant, so it's unfortunate that he is not more widely known.

.jpg)

Giovanni Battista Riccioli (1598-1671) holding a copy of his major work, the 1651 Almagestum Novum (The New Almagest).

The original Almagest, written in Greek by the Claudius Ptolemy (c.100-c.170) in the 2nd century, was an influential exposition on astronomy that presented evidence for geocentrism.

The Almagest had a profound influence on astronomical thought through the time of Copernicus.

(Image by Johann Gabriel Doppelmayer (1677-1750), plate 3 from the 1742 edition of the Atlas Coelestis (Homann: Nuremberg), via Wikimedia Commons)

Riccioli was born in Ferrara, Italy, in 1598, and he began studies in a Jesuit seminary in 1614, eventually becoming a Catholic priest in 1628. He was trained as a theologian, but he taught logic, physics, and metaphysics at the College of Parma from 1629 to 1632, where he did experiments with falling bodies and pendulums. As a student, Riccioli became interested in astronomy, and his interest was so deep that his Jesuit superiors decided that he should pursue astronomical research. To that end, he built a well equipped observatory at the College of Santa Lucia in Bologna and joined the circle of astronomers of that period that included Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695), who discovered Saturn's moon, Titan, and Giovanni Cassini (1625-1712), who discovered four moons of Saturn and the division in its rings that's named after him. Like his contemporary, Christiaan Huygens, Riccioli studied pendulums as a means for precision timekeeping, developing a pendulum with a period of one second with about 99% accuracy. I wrote about Huygens' work with pendulums in a previous article (Coupled Oscillators, November 15, 2011). Riccioli used a pendulum as a timepiece in falling body experiments from Bologna's Torre de Asinelli, where he confirmed Galileo's square-law observation.[3-4] He did notice that balls of different materials did travel at slightly different rates, a phenomenon that he correctly attributed to air resistance.[3] Riccioli's many experiments on falling bodies confirmed the validity of gravitational acceleration.[4] Riccioli's major work, the 1651 Almagestum Novum, consisted of ten books and a total of more than 1500 folio (38 cm x 25 cm) pages. It included detailed maps of the Moon, including one in which Riccioli named lunar features. His names form the basis for the lunar nomenclature of today in which craters were named after important astronomers. You can view Riccioli's lunar map at Wikimedia Commons. The site of the Apollo 11 Moon landing, the fiftieth anniversary of which we observed this year, received its Mare Tranquillitatis (Sea of Tranquility) name from Riccioli. Also tabulated were the motions of planets, comets, and novae.

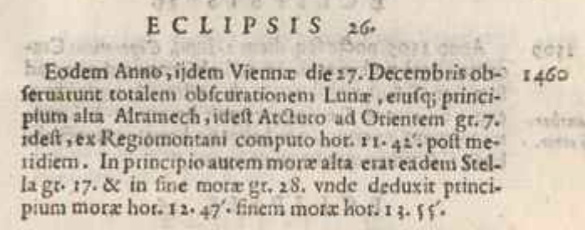

Description of a total lunar eclipse of December 17, 1460, from Book II, page 97, of Giovanni Riccioli's Almagestum novum. (Image from a PDF file of the book available from the ETH-Bibliothek Zürich rare book collection.)[2]

Several hundred of pages of Riccioli's 1651 Almagestum Novum concerns whether the Solar System is geocentric or heliocentric and considers such topics as whether the Earth rotates or is immobile. In Book IX of his Almagestum Novum, Riccioli presents 126 arguments about the motion of the Earth. Religion played just a small role in these arguments, since Riccioli stressed careful, reproducible experiments.[5] While it was conceded that the strict Ptolomaic model was dead, there was still the geocentric possibility that the planets circled the Sun while the stars, Moon, and Sun (with its planets, perhaps with the exception of Jupiter and Saturn) circled an immobile Earth. One argument against a rotating Earth was the observed absence of what is known today as the Coriolis effect.[5] Riccioli reasoned that were the Earth to rotate, a canon ball shot northward would veer to the east, since the Earth moves at different speeds at different latitudes.[6] However, he also claimed that there would be no deflection were the cannon ball fired to the east. In actuality, the Coriolis force would still angle the shot to the right. In any case, the effect is so small that its observation in Riccioli's time was not possible. Riccioli was wise enough to realize that birds in the sky would not be left behind by a rotating Earth, since they might share the same eastward movement. Another major argument that Riccioli presents against the Copernican theory is stellar size. Because of optical deficiencies, stars viewed through telescopes of his time all appeared as disks, rather than points of light. This disk appearance, known today as an Airy disk, is a result of the diffraction of light, but astronomers of the time thought that these disks were real.

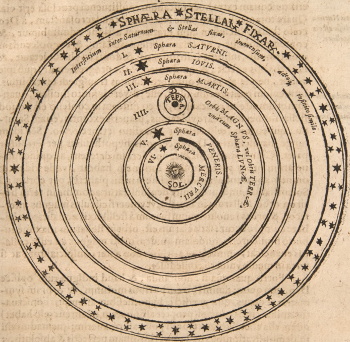

The heliocentric system from the 1596 Mysterium Cosmographicum of Johannes Kepler.

This ordering of the cosmos has an outermost sphere labeled, "sphaera stellar fixar," or sphere of fixed stars.

(Wikimedia Commons image from the University of Oklahoma History of Science Collections. Click for larger image.)

The Copernican theory presumed that the fixed stars were at a very large distance from Earth, since they showed no annual parallax. Riccioli and his Jesuit colleague, Francesco Grimaldi (1618-1663), made accurate measurements of stellar disk size and calculated what their physical sizes would be is they showed no parallax at the limits of measurement.[7] The sizes, of course, were huge; and, not knowing about Airy diffraction, this fact would cause concern for a proponent of the Copernican theory.

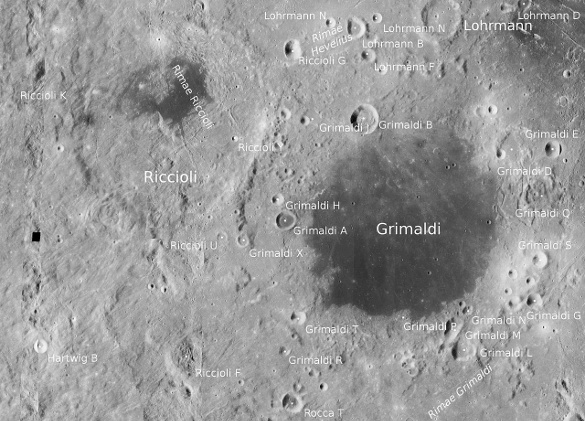

Lunar craters Riccioli and Grimaldi, named after Giovanni Battista Riccioli (1598-1671) and his colleague, Francesco Maria Grimaldi (1618-1663), who assisted with the stellar size measurements. The Riccioli crater is 146 km in diameter, and it has coordinates 3.0°S 74.3°W. The Grimaldi crater is 173.49 km in diameter, and it has coordinates 5.2°S 68.6°W (NASA Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter image, via Wikimedia Commons. Click for larger image.)

References:

- Helge Kragh and Kristian Hvidtfelt Nielsen, "Spreading the gospel: The Bohr atom popularised," arXiv, December 12, 2011.

- Giovanni Riccioli, "Almagestum novum," ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Shelf Mark: Rar 9471, http://dx.doi.org/10.3931/e-rara-520. A PDF file of Book is available here.

- Christopher M. Graney, "Beyond Galileo: A translation of Giovanni Battista Riccioli's experiments regarding falling bodies and "air drag", as reported in his 1651 Almagestum Novum," arXiv, May 21, 2012.

- Christopher M. Graney, "Anatomy of a fall: Giovanni Battista Riccioli and the story of g," Physics Today, vol. 65, no. 9 (September, 2012), pp. 36-40, doi: 10.1063/PT.3.1716.

- Christopher M. Graney, "126 Arguments Concerning the Motion of the Earth, as presented by Giovanni Battista Riccioli in his 1651 Almagestum Novum," arXiv, March 14, 2011.

- Christopher M. Graney, "The Coriolis Effect Apparently Described in Giovanni Battista Riccioli's Arguments Against the Motion of the Earth: An English Rendition of Almagestum Novum Part II, Book 9, Section 4, Chapter 21, Pages 425, 426-7," arXiv, December 16, 2010.

- Christopher M. Graney, "Not the Earth, but its orbit: Andre Tacquet and the question of star sizes in a heliocentric universe, arXiv, September 26, 2019.