The Dragonfly of Titan

August 12, 2019 The 1950s were exciting times for authors, but confusing times for readers. Many authors began to write in the Stream of Consciousness style in which random thoughts flowed from mind to pen with long, rambling sentences and little narrative coherence. It was in this decade that Jack Kerouac (1922-1969) published his 1957 On the Road, a work drafted on a typewriter in three weeks on a long scroll of paper. That's one way to save on staples and paperclips!

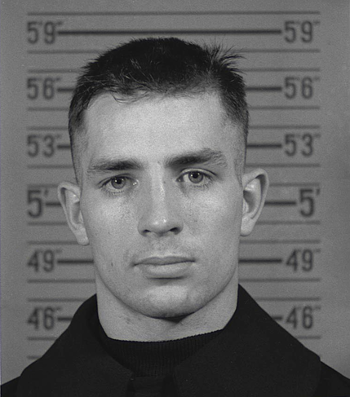

Jack Kerouac in 1943.

Kerouac was born to French Canadian parents and started learning English only at age six. He served in the United States Merchant Marine from 1942-1943, and joined the United States Navy in 1943.

His naval career lasted about a week, when naval doctors found cause to have him honorably discharged on psychiatric grounds as having a schizoid personality disorder; that is, he preferred a solitary lifestyle apart from others.

(Kerouac's 1943 Naval Reserve enlistment photograph, via Wikimedia Commons.)

The 1950s was the same decade in which Kurt Vonnegut (1922-2007) wrote The Sirens of Titan. This 1959 novel was quite different from the pulp science fiction space operas of that era. While The Sirens of Titan is not strictly a stream of consciousness novel, it does contain a torrent of mind-bending fictions based on such topics as quantum mechanics (the chrono-synclastic infundibulum) and machine intelligence (Salo, the Tralfamadorian robot). At the time of Vonnegut's writing, science had rendered ridiculous many of the premises of early science fiction, notably the idea that all planets of the Solar System could support life with some being inhabited by intelligent species. In these early stories, you would expect to find giants on Jupiter and dinosaurs on Venus. Vonnegut had the early idea that a moon of Saturn, Titan, could be habitable while Saturn itself was not.

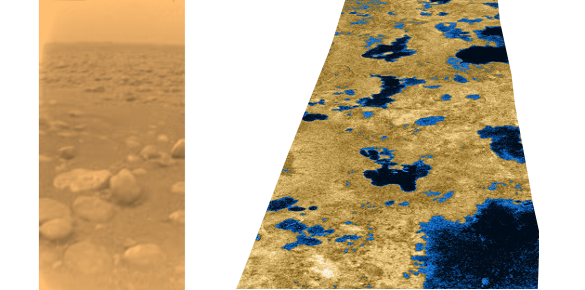

Titan images. Left image, a January 14, 2005, image of Titan's surface from the European Space Agency's Huygens probe during its successful descent onto Titan as part of the Cassini-Huygens mission (NASA image PIA07232). Right image, a radar image from the July 22, 2006, flyby of Titan by the Cassini spacecraft showing liquid lakes, which are darker than the surrounding terrain. The radar image resolution is about 500 meters (NASA image PIA09102).

Percival Lowell (1855-1916), who founded the Lowell Observatory at Flagstaff, Arizona to study the Martian canals, published a 1908 book entitled, "Mars as the Abode of Life."[1] Decades of Martian exploration by landers and rovers have not discovered any sign of life, either fossil or extant, on Mars. However, a newer book could be written with the title, "Titan as the Abode of Life," since our early explorations of Titan by the Pioneer 11 and Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 missions, and the extended observations by the Cassini mission as it was in orbit of Saturn for 13 years, have shown Titan to be an interesting place with an environment similar to an early Earth. While Titan's surface, where the temperature is about -200 °C, is hard-as-rock water ice, there is likely a liquid water ocean beneath the surface where it's warmer. Titan also has a substantial atmosphere that's mainly nitrogen, like Earth, but it has clouds of methane that produce a methane rain, and it also has light snows of organic compounds. Since its surface atmospheric pressure is 50% higher than that of Earth, a human wouldn't need a pressure suit. However, such astronauts would need an oxygen mask along with heated suits. Liquid water and complex organic chemical precursors to life must have existed together there for tens of thousands of years, so some prebiotic chemistry may have taken place. While such remote sensing has shown that Titan's weather, surface conditions, and co-existence of water and organic compounds are similar to those that existed at Earth's early history, there's nothing like being there. That's why NASA has decided to send a quadcopter drone the size of a automobile to Titan as its next billion dollar planetary science mission scheduled for launch in 2026.[2-4] The drone, called Dragonfly, will explore Titan's surface in a search for possible chemical precursors to life.[2-3]

NASA's Dragonfly drone at Titan in an artist's conception. In this image, Dragonfly is landing to take surface samples. (NASA/JHU-APL image.)

Although the Dragonfly is expected to launch in 2026, it won't arrive at Titan until 2034.[3] Dragonfly, which will be the first multi-rotor aerial vehicle on another Solar System body, will have eight rotors.[3] Dragonfly's present dimensions are three meters length and a little more than a meter's height. It will fly with the help of two sets of four propellers to allow Dragonfly to image the surface at altitude and land for a closer look.[4] It will be the first vehicle to fly its entire scientific payload from place to place to examine surface materials.[3] The project plan is to examine dozens of locations in search of prebiotic chemical precursors to life.[3] Titan's dense atmosphere and low gravity will enable Dragonfly to hover easily, and it will remain at its landing sites for a few weeks using drills on its skids for surface sampling.[2] The choice of landing sites is facilitated by the thirteen years of observation of Titan by Cassini. It's landing site will be at the equatorial "Shangri-La" dune fields that are similar to dunes in Namibia in southern Africa (see artist's conception, above).[3-4] Initially doing short jumps in that area, Dragonfly will eventually take longer jumps of up to 5 miles to finally reach the Selk impact crater, a chemically interesting area.[3-4] The total range of Dragonfly lander is expected to be 175 kilometers (108 miles), which is about double the combined distance traveled to date by all the Martian rovers.[3] In its expected 2.7 year mission, Dragonfly will also look for the Titan equivalent of earthquakes.[4] Says NASA Administrator, Jim Bridenstine,

"With the Dragonfly mission, NASA will once again do what no one else can do... Visiting this mysterious ocean world could revolutionize what we know about life in the universe. This cutting-edge mission would have been unthinkable even just a few years ago, but we're now ready for Dragonfly's amazing flight."[3]Bridenstine's viewpoint is amplified by Thomas Zurbuchen, the associate director of NASA's Science Mission Directorate,

"Titan is unlike any other place in the solar system, and Dragonfly is like no other mission... It's remarkable to think of this rotorcraft flying miles and miles across the organic sand dunes of Saturn's largest moon, exploring the processes that shape this extraordinary environment. Dragonfly will visit a world filled with a wide variety of organic compounds, which are the building blocks of life and could teach us about the origin of life itself."[3]

References:

- Percival Lowell, "Mars as the abode of life," (New York, Macmillan, 1908), via archive.org.

- Paul Voosen, "NASA to fly drone on Titan," Science, vol. 365, no. 6448 (July 5, 2019), p. 15, DOI: 10.1126/science.365.6448.15-a.

- Grey Hautaluoma and Alana Johnson, "NASA Selects Flying Mission to Study Titan for Origins, Signs of Life, NASA Press Release, June 27, 2019.

- Kerry Hensley and Anne Ball, "Life on Titan? New NASA Mission Will Find Out," Voice of America Website, July 6, 2019.

- Titan, Saturn's Largest Moon, NASA Solar System Website.