Women Nobel Laureates in 2018

October 22, 2018 As they say, you can learn a lot about a person by the company they keep, and this is true even in death. Stephen Hawking (1942-2018), died in March of this year, and his cremains are interred in Westminster Abbey, adjacent to the grave of Isaac Newton, and near the grave of Charles Darwin. Most scientists are buried in general cemeteries like everyone else. Physicist, Richard Feynman (1918-1988), is buried in a cemetery in Altadena, California, a location supposedly just a few miles from the apartment building in which the fictional physicists, Sheldon Cooper and Leonard Hofstadter live. In one episode of The Big Bang Theory (The Retraction Reaction, Season 11, no. 2), Sheldon and Leonard visit Feynman's grave site with Penny, Raj, and Howard.

Cemetery at the National Shrine of the North American Martyrs, Auriesville, New York.

Photo by the author, released under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 license.

(Click for larger image.)

In rare cases, scientists are honored by having their remains placed at the institution with which they are most associated. Albert Einstein's cremains were scattered around the grounds of the Institute for Advanced Study (Princeton, New Jersey). The cremains of Emmy Noether (1882-1935), a German theoretical physicist who found refuge at Bryn Mawr College (Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania) during the persecution of Jews in pre-war Germany, are interred under the walkway of the Bryn Mawr library. One of Noether's accomplishments was Noether's theorem which concerns conservation laws of motion. Although Hermann Weyl and Richard Brauer from Princeton attended her memorial service at Bryn Mawr, and she was given a posthumous written tribute by Einstein, Noether was excluded from most of the culture of science by her being a woman. When Noether lectured at the Institute for Advanced Study, she made the observation that she wasn't welcome at "the men's university, where nothing female is admitted."[1] How different science is in 2018, when two women, Donna Strickland and Frances Arnold have been awarded Nobel Prizes.

Emmy Noether (1882-1935), as shown in a 1930 photograph.

Emmy's father, Max Noether, was a mathematician who contracted polio at age 14, and this affliction likely prompted his career choice of mathematics.

Max was one of the founders of algebraic geometry, while Emmy became a prominent figure in abstract algebra.

(Photograph by Konrad Jacobs, Erlangen, Germany, via Wikimedia Commons. modified for artistic effect.)

Women have been working in science for quite a while, but only recently have they been given appropriate recognition. Today, so many women are working as scientists, engineers and mathematicians that they have their own professional organizations. Here are the largest:

• Association for Women in Science (AWIS)Several centuries ago, the only women practicing science were the wives, daughters and sisters who acted as assistants to their scientist kin. Caroline Herschel, the sister of the astronomer, William Herschel, assisted her brother's astronomical observations, but not during his discovery of the planet, Uranus. While the "Boy's Club" culture of early science was responsible for the repression of women scientists, it's interesting to note that women scientists have been just as repressive of their own sex. A 2012 paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) provides evidence that female scientists are also biased against women in science.[2-3] Closer to our time, we have the archetypal woman scientist, Marie Sklodowska-Curie, who shared the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics with her husband, Pierre, for their work with radioactive elements. Pierre died in 1907, and Marie went on to receive the 1911 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for her isolation of radium.

• Association for Women in Mathematics (AWM)

• Society of Women Engineers (SWE)

• Sigma Delta Epsilon/Graduate Women in Science (GWIS)

• Association for Women Geoscientists (AWG)

• National Center for Women & Information Technology (NCWIT) • LinuxChix

Marie Sklodowska-Curie (1867-1934), circa 1898.

Curie died from aplastic anemia, apparently a consequence of her long-term exposure to ionizing radiation, the dangerous effects of which were not known at the time of her work.

Her papers from the 1890s are so contaminated with radioisotopes that they are kept in lead-lined boxes.

(Wikimedia Commons image, modified for artistic effect.)

Prior to 2018, there was just one woman Nobel Physics Laureate other than Curie, Maria Goeppert-Mayer, and three Nobel Chemistry Laureates other than Curie, Irène Joliot-Curie (daughter of Marie Curie and Pierre Curie), Dorothy Hodgkin, and Ada Yonath. In 2018, we can now add Donna Strickland in physics,[4-7] and Frances Arnold in chemistry.[8-10] Donna Strickland of the University of Waterloo, Canada, shared half of the 9 million Swedish Krona (1 million dollar) physics prize with Gérard Mourou of the École Polytechnique, Palaiseau, France and the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, "for their method of generating high-intensity, ultra-short optical pulses." This is in recognition of Strickland's doctoral thesis done under Mourou's supervision that established the technology of chirped pulse amplification (CPA).[7] CPA allowed creation of laser radiation of extreme intensity.

A laser physicist in her natural environment - Donna Strickland, Nobel Physics Laureate for 2018. (Left image and right image via the University of Waterloo.)

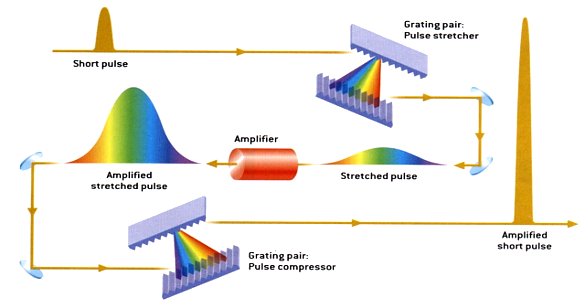

The problem in creating ultrashort high-intensity laser pulses is that optical materials, including the amplification media that increase the light intensity, have defects. Pounding these defects with high optical power ends up destroying the material. Strickland and Mourou's 1985 solution was to stretch the laser pulses in time to reduce their peak power before amplification, then compressing the stretched optical pulse to a shorter time (see figure).[5] Using this technique, Strickland and Mourou were able to convert a 300 picosecond pulse to one having 1 mJ of energy contained in a 2 picosecond pulse.[7] This converts to 0.5 gigawatts.

Chirped pulse amplification. In this illustration, the chirp is illustrated by colors. The gain medium in early experiments was Nd:YAG glass, and today it's usually Ti:sapphire. (Fig. 5 of ref. 5, via the Center for Ultrafast Optical Science, University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.[5] Click for larger image.)

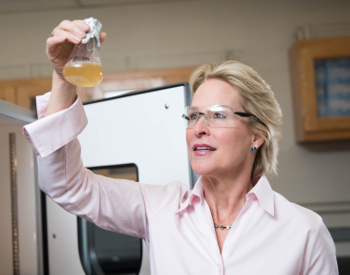

Half of the 9 million Swedish krona (1 million dollar) Nobel Prize in Chemistry for 2018 was awarded to Frances H. Arnold of the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California. In 1993, Arnold followed-up on a 1984 suggestion by the 1967 Nobel Chemistry Laureate, Manfred Eigen, that it might be possible to direct the evolution of enzymes, which are proteins that catalyse chemical reactions. Enzymes allow a more environmentally friendly manufacture of many chemical substances, such as pharmaceuticals and biofuels, since specialty enzymes can replace toxic chemicals in many industrial processes. Eigen thought that improved enzymes could be created in an iterative evolutionary process.

Frances Arnold, a 2018 Nobel Chemistry Laureate.

Her award was for "the directed evolution of enzymes."

(Caltech photo.)

Arnold's host institution, the California Institute of Technology, has had 38 other Nobel laureates, including Kip Thorne (BS degree in 1962) and Barry Barish, winners of the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physics; Robert Grubbs, winner of the 2005 Nobel Prize in Chemistry; David Politzer, recipient of the 2004 Nobel Prize in Physics; and Rudy Marcus, sole winner of the 1992 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.[10] It's always interesting to read how the winners received the news. Arnold was in Dallas, Texas, to give a talk at the at University of Texas when she received the call at around 4 AM local time. Says Arnold, "It's not something I was expecting."[10] Arnold received an undergraduate degree in mechanical and aerospace engineering from Princeton University and a Ph.D. in chemical engineering from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1985. She started at Caltech in 1986, and she became a full professor there in 1996, becoming the Linus Pauling Professor in 2017. Arnold has been the director of Caltech's Bioengineering Center since 2013.[10] Arnold is one of the few to have been elected to all the US National Academies, the National Academy of Engineering in 2000, the National Academy of Medicine in 2004, and the National Academy of Sciences in 2008.[10] She is also a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and she received the National Medal of Technology and Innovation in 2011.[10] Says Arnold, who is presently engineering bacteria to economically make chemicals not found in nature and with less toxic waste,

"My entire career I have been concerned about the damage we are doing to the planet and each other... Science and technology can play a major role in mitigating our negative influences on the environment. Changing behavior is even more important. However, I feel that change is easier when there are good, economically viable alternatives to harmful habits."[10]

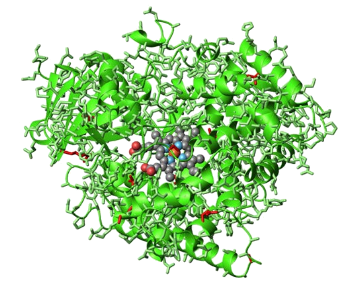

An evolved biocatalyst for cyclopropanation.

mutated side chains of the cytochrome P411 variant of cytochrome P450 are shown in red.

(Fig. 5 of ref. 9.)

References:

- Auguste Dick, "Emmy Noether: 1882–1935," H. I. Blocher, trans., Birkhäuser (Boston, March 19, 2012), ISBN-13: 978-1468405378, p. 81, as quoted at Wikipedia.

- Scott Jaschik, "Smoking Gun on Sexism?," Inside Higher Education, September 21, 2012

- Corinne A. Moss-Racusin, John F. Dovidio, Victoria L. Brescoll, Mark J. Graham and Jo Handelsman, "Science faculty's subtle gender biases favor male students," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, September 17, 2012; a PDF copy of the paper can be accessed here.

- The Nobel Prize in Physics 2018, Nobel Prize Foundation.

- The Nobel Prize in Physics 2018 Advanced Information, Nobel Prize Foundation (PDF File).

- Feridun Hamdullahpur, "President's Blog-Honoured to Have Donna Strickland as the University of Waterloo's First Nobel Prize Winner," University of Waterloo, October 3, 2018.

- Donna Strickland and Gerard Mourou, "Compression of amplified chirped optical pulses," Optics Communications, vol. 55, no. 6, (October 15, 1985), pp. 447-449, https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-4018(85)90151-8.

- The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2018, Nobel Prize Foundation.

- The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2018 Advanced Information, Nobel Prize Foundation (PDF File).

- Whitney Clavin, "Frances Arnold Wins 2018 Nobel Prize in Chemistry," California Institute of Technology Press Release, October 3, 2018.