Amorphous Diamond

March 5, 2018 I'm showing my age as I fondly recall watching the Doublemint Twins television commercials of the early 1960s.[1] These commercials in glorious, low resolution, black-and-white continued for many years thereafter, eventually transitioning to color. They portrayed identical twin American teenagers, exclusively white for at least the first decade (see cartoon), who appeared to be having a lot of fun while chewing the Wrigley brand gum.

People from the Mediterranean countries have darker skin than most people identified as Caucasian. (Nympha Palermo by Gemma Grimaldi, Cartoon No. 24, "Barbie.")

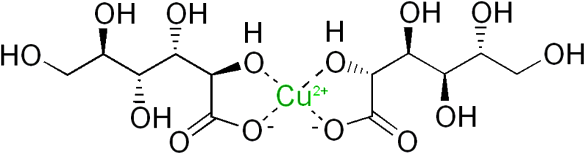

While Wrigley's had provenance of the identical twin landscape of television commercials, that didn't stop Warner-Lambert from launching similarly themed commercials for Certs.[2] The memorable part of these commercials was the debate about whether Certs was a breath mint or a candy mint. This question was resolved by declaring Certs to be both a candy mint and a breath mint. Warner-Lambert, however, decided that Certs was actually a breath mint in 1999, when the United States Customs Service decided that Certs was a candy in the more highly taxed tariff class 2106.90.99. On appeal to the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, Warner-Lambert's argument that Certs should be classified as 3306.90.00, "Preparations for oral or dental hygiene," was upheld.[3] So, legally, Certs is a breath mint. The chemists among us may remember another part of the Certs advertising campaign, that each Certs mint had a "golden drop of Retsyn." Retsyn is the trademark for a mixture of copper gluconate, partially hydrogenated cottonseed oil, and flavoring, and it's the copper gluconate that gives Certs its green flecks. There's actually more than marketing behind the addition of Retsyn to Certs, since copper is known to have antimicrobial properties.

Chemical structure of copper gluconate. Copper gluconate, which is water soluble, is the copper salt of D-gluconic acid. (Image by Edgar181, modified, via Wikimedia Commons)

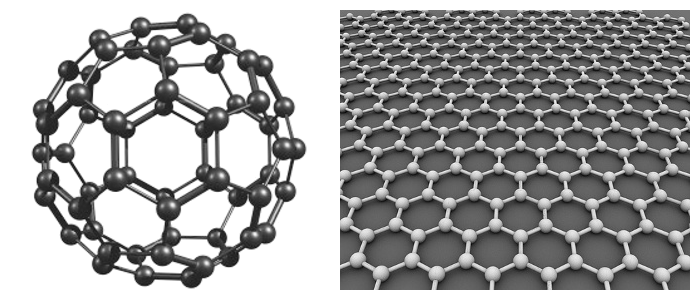

Gerald Holton, in his 1973 book, "Thematic Origins of Scientific Thought: Kepler to Einstein," wrote about a scientific analogy to the dual resolution of the Certs dichotomy.[4] In this book, Holton defined important conceptual elements in the physical sciences that he called thema. While thema such as conservation laws help to guide scientific development, the most fundamental thema coexist with their antithetical, anti-thema. An example of this is wave-particle duality. Apparently, great physics involves entertaining two contradictory ideas at the same time. I thought of this when I read the title of a recent open access paper, "Deduced elasticity of sp3-bonded amorphous diamond," in Applied Physics Letters (APL).[5-6] Indeed, diamond is defined by one particular structure; namely, the diamond cubic crystal structure having the the Fd(3-bar)m space group. If the structure is amorphous, then it isn't diamond. Of course, I realized that the authors intended to distinguish diamond-like properties from those of amorphous carbon; and, sp3 bonding is what's found in diamond, not graphite. So, this allotropic form of carbon is both diamond, and not really diamond - It's two materials in one. By now we're accustomed to the plethora of carbon allotropes, most of which are listed below:

• Diamond

• Graphite

• Graphene

• Amorphous carbon

• Buckminsterfullerene

• Carbon nanotubes

• Glassy carbon

• Lonsdaleite (hexagonal diamond)

• Linear acetylenic carbon

Diagram of buckminsterfullerene (C60), left, and a pictorial representation of a graphene sheet. These dissimilar-looking materials both have carbon atoms that are sp2 bonded. (C60 image from Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology State University. Graphene image by Alexander Alus, via Wikimedia Commons.)

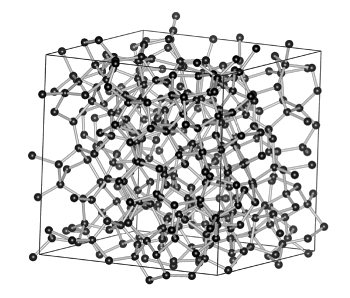

The synthesis of amorphous diamond was first reported last year by a Chinese and American research team with members from the Center for High Pressure Science and Technology Advanced Research (HPSTAR, Shanghai, China), the Carnegie Institution of Washington (Argonne, Illinois, and Washington, DC), Argonne National Laboratory (Argonne, Illinois), Stanford University (Stanford, California), and the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory (Menlo Park, California).[7] High pressure and in situ laser heating were used to convert glassy carbon into amorphous diamond that was stable when brought to room temperature and pressure. This material was shown to have sp3 bonding between carbon atoms and an incompressibility that was comparable to that of crystalline diamond.[7]

Structural model of amorphous diamond, as deduced by a computer simulation.

(Fig. 4a of Ref. 7, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.)

The paper in Applied Physics Letters was authored by the father-son team of Arthur Ballato and John Ballato.[6] Arthur Ballato is the retired Chief Scientist of the US Army Communications-Electronics R&D Center, Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. The APL paper computes some physical properties of amorphous diamond using a methodology (Voigt-Reuss-Hill) in which crystal values are averaged over all orientations to give the values for the amorphous phase.[5] While all carbon atoms (ignoring the small fraction that are on the surface) in actual diamond are sp3-bonded, amorphous diamond has a small fraction of sp2-bonded carbon atoms, the same bonding found in graphite.[6] Still, the amorphous material shows very desirable mechanical properties.[6] The Clemson team calculated the elastic and mechanical properties by the Voigt-Reuss-Hill methodology, named after its creators. Voigt averaged elastic stiffness constants over all directions in space to estimate the properties of an amorphous solid based on its crystalline counterpart, Reuss did the same for the elastic compliance constants, and Hill produced a synthesis of these methods.[5] The approach involves relaxing the single crystal constants to obtain equivalent isotropic values for the amorphous solid.[5] The Clemson team had previously applied this methodology to glassy sapphire.[6] Says John Ballato,

"We employed a modeling approach by which one can use the properties of crystalline diamond to deduce the properties of the glassy diamond analog... In this work, we inferred the elastic properties of this new phase of diamond from measured properties of crystalline diamond."[6]The calculated mechanical constants for amorphous diamond appear below.[5]

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| c11 | 1156.5 GPa |

| c12 | 87.6 GPa |

| c44 | 534.5 GPa |

| Young's Modulus | 1144.2 GPa |

| bulk modulus | 443.9 GPa |

| Poisson's ratio | 0.0704 |

References:

- 1950s-60s Wrigley's Doublemint Commercial (Violin Players), YouTube video by HRTVFan2, October 30, 2015.

- Vintage - Certs Breath Mints Commercial, YouTube video by Ron Flaviano, October 17, 2011.

- WARNER LAMBERT COMPANY v. UNITED STATES, United States Court of Appeals,Federal Circuit, WARNER-LAMBERT COMPANY, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. UNITED STATES, Defendant-Appellee, No. 04-1489, Decided, May 11, 2005 (via findlaw.com).

- Gerald Holton, "Thematic Origins of Scientific Thought: Kepler to Einstein," Harvard University Press, New edition (May 25, 1988), Paperback, 504 pages, ISBN-13: 978-0674877481 (via Amazon).

- J. Ballato and A. Ballato, "Deduced elasticity of sp3-bonded amorphous diamond," Applied Physics Letters, vol. 111, no. 22 (November 28, 2017), Article no. 221901, doi: https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5005822. This is an open-access article with a PDF file here.

- Deducing the properties of a new form of diamond, American Institute of Physics Press Release, November 30, 2017.

- Z. Zeng, L. Yang, Q. Zeng, H. Lou, H. Sheng, J. Wen, D. J. Miller, Y. Meng, W. Yang, W. L. Mao, and H. K. Mao, "Synthesis of quenchable amorphous diamond," Nature Communications, vol. 8, Article no. 322 (August 27, 2017), doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00395-w. This is an open-access article with a PDF file here.