Alfred Loomis

February 26, 2018 Laboratory research is interesting, but another enjoyable aspect of working in a large research organization is the company of many interesting colleagues. Our particular research department had a tradition of lunching together at our site's cafeteria. This cafeteria was called "Cafe Alchem," not as any homage to alchemy, but because our company was originally named Allied Chemical. There was interesting table conversation about science, but also occasional lapses into finance, such as whether to buy Treasury Bonds or gold. My personal opinion is that, unless you're making integrated circuits, it's never a good time to buy gold. Although we had none at our lunch table, there are doomsday preppers who keep gold as the only stable currency in troubled times. It's probably better to invest in sacks of rice and cartons of condoms. When you tire of eating rice, you can trade some condoms for brussels sprouts. At one point, when the state lottery had reached a phenomenal payout, we talked about what we would do with all that money. Our director was a scientist who had chosen that career since he really enjoyed doing science. He had an early interest in rocks and minerals, so he eventually became a crystal grower; and, like me, he had a home laboratory in his youth. He said that he would use the lottery winning to build a private laboratory so he could experiment with whatever caught his interest. I happened to think of him when I viewed the recent public television showing of "The American Experience - The Secret of Tuxedo Park."[1] That episode was a biography of Alfred Lee Loomis (1887-1975), an unknown amateur scientist who had enough money to build a world-class scientific laboratory and become an autodidact scientist of the first order. He was so skilled in physics that he was a significant contributor to radar development during World War II.

Alfred Loomis (1887-1975), on a visit to consider the feasibility of a 184-inch cyclotron at Berkeley, March_29, 1940.

Loomis was unknown to me before I watched his biography on public television. I can be excused for my ignorance, since Loomis disliked publicity of any sort, and his historical footprint is accordingly very small.

(A Wikimedia Commons image, modified for artistic effect.)

His laboratory, at Tuxedo Park, New York, near New York City, was funded by his career as an investment banker. Born into a family of social prominence, Loomis was well schooled, attending Phillips Academy for his secondary school education, then Yale University and Harvard Law School. After his cum laude graduation from Harvard Law School, Loomis joined the New York law firm, Winthrop & Stimson, to practice corporate law. He married Boston socialite, Elizabeth Farnsworth, in 1912 with whom he had three sons. Loomis served in the US Army during World War I, reaching the rank of lieutenant colonel. This military service changed the course of his life, since he was stationed at the Aberdeen Proving Ground near Aberdeen, Maryland and tasked with improvements in ballistics. At Aberdeen, Loomis invented a device, called the Aberdeen Chronograph, for an improved measurement of the muzzle velocity of artillery shells. At Aberdeen, Loomis worked with Robert W. Wood, a physicist at nearby Johns Hopkins University, who inspired his interests in experimental physics and the use of physical principles for invention. Having decided that the practice of law had limited financial rewards, Loomis joined his brother-in-law, Landon K. Thorne, as investment bankers who specialized in public utilities with an emphasis on rural electrification and consolidation of small electric companies into larger holding companies. Loomis' analytical mind foresaw the stock market crash of 1929, and he and Thorne cashed-out before crash. After the crash, they were able to acquire stock in companies at low prices, and Loomis had enough money to build his personal laboratory and enough time for his independent scientific pursuits. Loomis' wealth allowed him to equip his laboratory in a fashion not possible for other scientists, he did early experiments in ultrasonics, electroencephalography, and did considerable experimentation with radio. Loomis discovered the K-complex brainwave, which is active during sleep, in 1937. His reputation grew to such an extent that his laboratory was visited by such scientific luminaries as Niels Bohr, Albert Einstein, Enrico Fermi, James Franck, and Werner Heisenberg. Loomis helped to secure funding for Ernest Lawrence in construction of a 184-inch cyclotron. Eventually, with World War II on the horizon, Loomis moved his laboratory to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to work jointly with physicists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

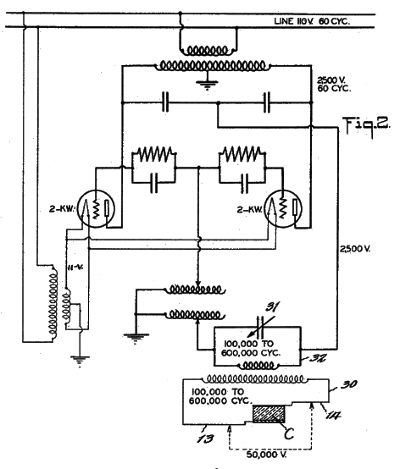

Fig. 2 from US Patent No. 1,734,975, "Method and apparatus for forming emulsions and the like," by Alfred L Loomis and Wood Robert Williams, November 12, 1929.

This early Loomis patent reflected his interest in ultrasonics. In this example, ultrasonic mixing of liquids is accomplished by a simple multivibrator oscillator generating extremely high voltages to excite a huge quartz crystal, shown as C.

Such high voltages were required, since the more efficient piezoelectric material, lead-zirconate-titanate, had not yet been discovered.

(Via Google Patents.)[2]

Although Loomis was a participant in early meetings on the Manhattan Project, his research efforts during World War II were focused on radar. Loomis had an early interest in microwave radar; however, the electronics of the time were crude, and microwave radar was not feasible until the development of the cavity magnetron by British scientists. When the magnetron design was revealed to the Americans, Loomis realized that microwave radar would give an important military advantage. Vannevar Bush, director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development during World War II about whom I wrote an earlier article (Basic Research, October 22, 2010), appointed Loomis to the National Defense Research Committee as chairman of the Microwave Committee. Loomis quickly founded the MIT Radiation Laboratory for the development of radar, the laboratory being directed by Lee DuBridge, who was later the president of the California Institute of Technology. Loomis, having connections in high places in academia, government, and industry, was able to remove bureaucratic obstacles to the development of a radar system having a 10 centimeter operating wavelength (3 GHz). This radar was used for radiolocation of submarines and aircraft, and for automatic gun control of anti-aircraft batteries. Loomis invented a radio navigation system called LORAN, an acronym for Loomis Radio Navigation, that was developed during the war along with radar. This ground-based system, a predecessor to GPS, was only accurate to about ten miles, but it was useful for trans-Atlantic and trans-Pacific navigation. LORAN was a hyperbolic radio navigation system based on timed radio signals from at least two of several widely-spaced radio transmitters operating at about 2 MHz. At the war's end, there were 72 LORAN transmitters, and more than 75,000 ships and aircraft were fitted with receivers. Loomis, whose accomplishments prior to the war earned him election to the National Academy of Sciences in 1940, could have used his accomplishments during the war to secure a place in the highest levels of government research administration. Instead, he retreated completely from public life, closing his laboratory in 1947. Loomis had always valued his privacy; and, perhaps retreating from the scandal of having an extramarital affair with a colleague's wife, whom he married after a 1945 divorce from his first wife, he retired to an East Hampton, New York, house and never granted interviews. Loomis and his wife lived there for thirty years, until his death in 1975. The broad strokes of Loomis' scientific interests beyond radio and radar can be seen in this short list of some of his publications.

• The physical and biological effects of high-frequency sound-waves of great intensity.[3]

• An Attempt to Induce Mutation in Drosophila melanogaster by Means of Supersonic Vibrations.[4]

• An apparent lunar effect in time determinations at Greenwich and Washington.[5]

• Further investigations of an apparent lunar effect in time determinations.[6]

• Brain potentials during hypnosis.[7]

• Changes in human brain potentials during the onset of sleep.[8]

References:

- The American Experience - The Secret of Tuxedo Park, January 16, 2018.

- Alfred L Loomis and Wood Robert Williams, "Method and apparatus for forming emulsions and the like," US Patent No. 1,734,975, November 12, 1929 (via Google Patents).

- R.W. Wood and Alfred L. Loomis, "The physical and biological effects of high-frequency sound-waves of great intensity," Philosophical Magazine, ser. 7, vol. 4, no. 22 (1927), pp. 417-436, https://doi.org/10.1080/14786440908564348.

- A. H. Hersh, Enoch Karrer, and Alfred L. Loomis, "An Attempt to Induce Mutation in Drosophila melanogaster by Means of Supersonic Vibrations," The American Naturalist, vol. 64, no. 695 (November-December, 1930), pp. 552-559, https://doi.org/10.1086/280339.

- A. L. Loomis and H. T. Stetson, "An apparent lunar effect in time determinations at Greenwich and Washington," Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, vol. 93, no. 6, (April 12, 1933), pp. 444-447, https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/93.6.444.

- A. L. Loomis and H. T. Stetson, "Further investigations of an apparent lunar effect in time determinations," Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, vol. 95, no. 5 (March 1, 1935), pp. 452-466, https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/95.5.452.

- Alfred L. Loomis, E. Newton Harvey, and Garret Hobart, "Brain potentials during hypnosis," Science, vol. 83, no. 2149 (March 6, 1936), pp. 239-241, DOI: 10.1126/science.83.2149.239.

- H. Davis, P.A. Davis, A.L. Loomis, E.N. Harvey, and G. Hobart, "Changes in human brain potentials during the onset of sleep," Science, vol. 86, no. 2237 (November 12, 1937), pp. 448-450, DOI: 10.1126/science.86.2237.448.