Voice Synthesis

June 26, 2017

Two

episodes of

Star Trek: The Original Series, "

The Cage," were a

remix of the unaired

pilot. While there is much memorable content for

science fiction fans in these episodes,

computer scientists would especially enjoy

Spock's simulating Kirk's voice on some primitive looking

mainframe-style computers as part of a

deception to take

command of the

Enterprise.

As I wrote in a

previous article (Computers as Listeners and Speakers, November 4, 2013), the characteristics of the human voice make it amenable to easy

synthesis. First,

speech signals are contained in a limited

audio frequency band below 20

kHz, while

intelligible speech is contained in frequencies between

300-3400 Hz, with most of the amplitude contained between 80-260

Hz.

The limited band for intelligible speech was important to early

telephone system, since

high frequency transmission lines and

components would have been

expensive. Even at that time,

Bell Labs was interested in reducing the transmission cost further, so there was

research in

speech synthesis with the idea that an effective system would allow a lower data rate, data rate in those days before

computers meaning the number of

signal tones.

Bell Labs

acoustical engineer,

Homer Dudley, demonstrated that a crude simulation of human speech was possible even in the days of

vacuum tube electronics by creating a system called the

vocoder.[1-5] Some examples of Vocoded speech can be found on

YouTube.[1]

In the vocoder system, Dudley used a bank of

audio filters to determine the

amplitude of the speech signal in each frequency band. These amplitudes alone were

transmitted to a remote bank of

oscillators to reconstructed the signal. In this manner, the vocoder allowed

compression and

multiplexing of many voice

channels over a single

submarine cable.

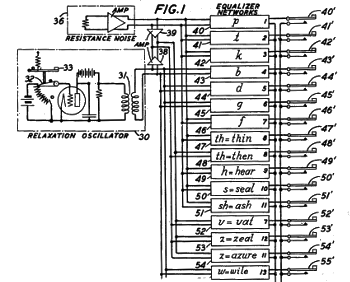

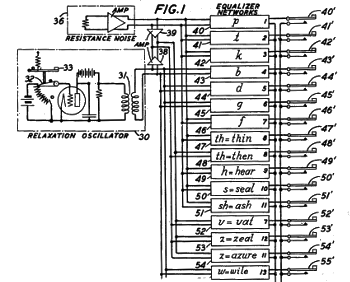

| Portion of fig. 1 of US Patent No. 2,194,298, "System for the artificial production of vocal or other sounds," by Homer W. Dudley, March 19, 1940.

As the circuit shows, Dudley realized that white noise is an important component of speech.

(Via Google Patents.[4]) |

It doesn't take too long for a "

person having ordinary skill in the art" to realize that the vocoder data signals could be

transposed to make a

telephone call unintelligible to a

wiretapper. Such

encryption of the speech signal allowed secure voice communications during

World War II.

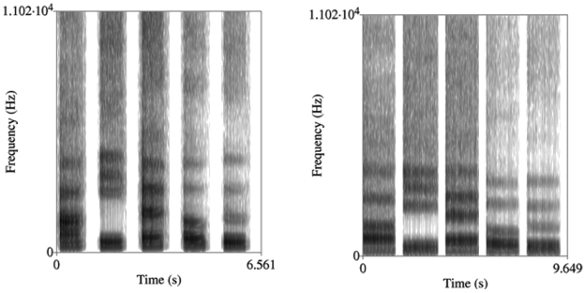

The vocoder operated on band-limited signals equally spaced over an extended frequency range, but synthesis of human speech requires fewer bands. Human speech is contained in definite frequency bands called

formants which arise from the way that human speech is generated.

Air flow through the

larynx produces an excitation signal that excites

resonances in the

vocal tract, so the signal

amplitude is most prominent at these formant frequencies (see figure).

The development of computers allowed creation of a

speech synthesis technique called

formant synthesis, which is

modeled on the physical production of sound in the

human vocal tract. It was implemented using

linear predictive coding (LPC) in the

source–filter model of speech production.

Texas Instruments created an

LPC integrated circuit that was used in its

Speak & Spell toy.

Today, text to speech is common, and my

e-book reader has a very good

text-to-speech feature with both male and female speakers. However, it does have the tendency to comically render some unusual

character names. Apple's

Siri talking

virtual assistant was introduced in 2011, and it was a featured

plot element in an episode of

The Big Bang Theory (Season 5, episode 14, "

The Beta Test Initiation," January 26, 2012). The

Amazon Echo was introduced in 2015. All of these lagged significantly behind the introduction of the

HAL 9000 in 1997 (according to the film,

2001: A Space Odyssey).

Early analog electronic music synthesizers were capable of making a wide variety of sounds with a limited assortment of

oscillators,

filters, and

amplitude modulators. In 1978,

Werner Kaegi and

Stan Tempelaars of the

University of Utrecht (Utrecht, The Netherlands) developed a simple technique for generating vocal sounds with the limited analog circuitry available at the time.[7] Shortly thereafter, I designed and built an accessory device that implemented their VOSIM technique on analog electronic music synthesizers (see photo).[8]

While speech synthesis has now become common, what isn't common is Spock's type of speech synthesis that I mentioned earlier; that is, synthesizing a specific voice. It would be interesting to have a summary of the daily news read by

Walter Cronkite (1916-2009) and

Edward R. Murrow (1908-1965), or an analysis of

Donald Trump's tweets by

Andy Rooney (1919-2011). Research along these lines is being conducted by computer scientists at

Princeton University and

Adobe Research.[9-11]

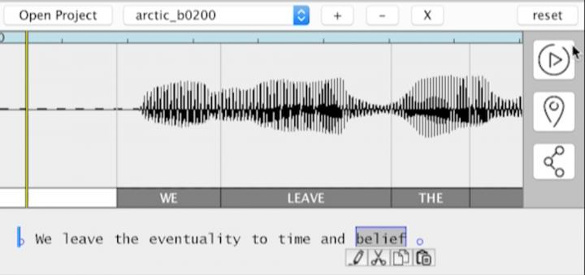

The developed

software, named VoCo, can be described as a

word processor for speech, one with the ability to add and modify individual words of a given speaker.[10] The new words are automatically synthesized in the same speaker's voice, and it's not required that these words appear in the original

recording.[10] This technology could eventually allow

information utilities to speak in a more natural voice.[10]

This work, which is scheduled to be presented at the

Association for Computing Machinery SIGGRAPH conference in July, 2017, will be

published in the July issue of the

journal,

Transactions on Graphics.[9] VoCo's

graphical user interface resembles that of other audio editing software, such as

Audacity, the

free-and-open-source software (FOSS) that

Tikalon uses for its audio editing. VoCo includes an additional text

transcript of the

audio track to allow a user to replace or insert new words. VoCo uses the transcript information to automatically synthesize new words by stitching together audio from elsewhere in the audio track.[10]

VoCo functions by searching the audio file of a voice recording and selecting the best possible combinations of

phonemes to synthesize new words in the same voice. There's a lot of computing at play here, since VoCo needs to find the phonemes in the original file, and then smoothly stitch some of them together to create the word. The words are

pronounced with different

intonation depending on the context to create a natural sound.[10] If the synthesized word doesn't sound quite right, there are options for changes.[10]

In a test of the VoCo system, listeners decided that VoCo recording were real recordings more than 60 percent of the time.[10] The

technology behind VoCo can allow creation of a more natural "

robotic" voice for people who have lost their voices, an example being famed

physicist,

Stephen Hawking.[10]

Zeyu Jin, a

graduate student in

Computer Science at Princeton University, relates the following story.

"We were approached by a man who has a neurodegenerative disease and can only speak through a text to speech system controlled by his eyelids... The voice sounds robotic, like the system used by Steven Hawking, but he wants his young daughter to hear his real voice. It might one day be possible to analyze past recordings of him speaking and created an assistive device that speaks in his own voice."[10]

References:

- The Voder - Homer Dudley (Bell Labs) 1939, YouTube video by MonoThyratron, July 9, 2011.

- Homer W Dudley, "System for the artificial production of vocal or other sounds," US Patent No. 2,121,142, June 21, 1938.

- Homer W Dudley, "Signal transmission," US Patent No. 2,151,091, March 21, 1939.

- Homer W. Dudley, "System for the artificial production of vocal or other sounds," US Patent No. 2,194,298, March 19, 1940

- Homer W Dudley, "Production of artificial speech," US Patent No. 2,243,525, May 27, 1941.

- Daniel E. Re, Jillian J. M. O'Connor, Patrick J. Bennett and David R. Feinberg, "Preferences for Very Low and Very High Voice Pitch in Humans," PLoS ONE, vol. 7, no. 3 (March 5, 2012), Article No. e32719, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0032719.

- Werner Kaegi and Stan Tempelaars, "VOSIM--A New Sound Synthesis System,"Journal of the Audio Engineering Society, vol. 26, no. 6 (June, 1978), pp. 418-425.

- Devlin M. Gualtieri, "A VOSIM Processor," Electronotes, vol. 13, no. 130 (October, 1981).

- Zeyu Jin, Gautham J. Mysore, Stephen DiVerdi, Jingwan Lu, and Adam Finkelstein. 2017, "VoCo: Text-based Insertion and Replacement in Audio Narration," ACM Trans. Graph., vol. 36, no. 4, Article 96 (To be Published, July, 2017), 13 pages..

- Technology edits voices like text, Princeton University Press Release, May 15, 2017.

- Video Demonstration of the VoCo System at Princeton University Web Site. Also as a YouTube Video, "VoCo: Text-based Insertion and Replacement in Audio Narration," by Adam Finkelstein, May 11, 2017.