150 Years of Transatlantic Telegraphy

January 5, 2017

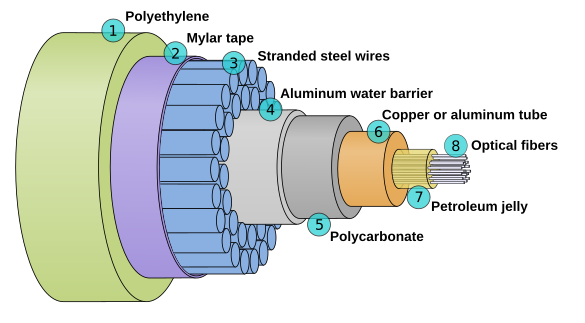

Optical fibers spanning the

Atlantic carry the

Internet between the

major population centers of the world. The multitude of Atlantic

fiberoptic cables now in place are technological marvels.

Some of these have a

data rate far exceeding a

terabit/second with a

latency under 100

milliseconds. A standard

DVD optical disk of the type I use to

back up files on my

computer has a capacity slightly less than 0.005 terabytes.

Transatlantic data communication was first accomplished a few

decades after the

invention and improvement of the

telegraph by

Samuel Morse and many others in the 1830s. The first

transatlantic telegraph cables were placed in 1857 and 1858, but they did not work as planned. The idea that an

undersea cable, suitable toughened for its

environment, would work as well as its terrestrial counterparts was fundamentally flawed.

Air, which

electrically approximates a

vacuum to a large extent, has the lowest possible

relative permittivity, also known as the dielectric constant, with a value of 1.00.

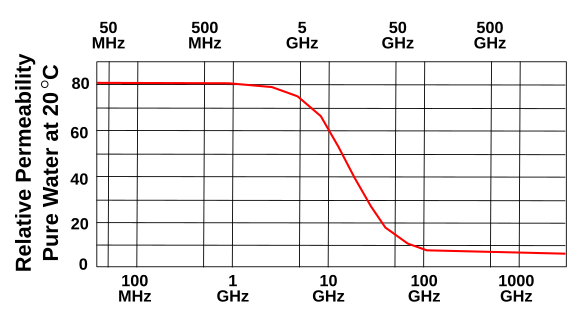

Water has a very high dielectric constant at low, telegraph

frequencies (see figure), and

seawater has nearly an identical value, so these undersea cables had a high associated

capacitance. That capacitance, combined with the

electrical resistance of the cables, resulted in a very low data rate and high

signal loss.

Signalling was possible only when the cables were driven by extremely high

currents, and this resulted in their early demise.

Oliver Heaviside, a

maverick but knowledgeable

physicist and

electrical engineer of that era, explained all this by a simplification of

Maxwell's equations.

More importantly, Heaviside devised a solution to the problem; namely, adding

inductors, called

loading coils, along the transmission line to balance the capacitance. Another physicist,

William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) proposed that a reduction in cable resistance through use of a larger diameter

conductor, and thicker cable

insulation to reduce capacitance, would prove beneficial.

This first transatlantic cable was laid by two

ships, the

USS Niagara and the

HMS Agamemnon, each of which each carried half the cable.[2] They met in mid-ocean, the two cables were

spliced together, and they laid the cable to the opposite

shores.[2] The seven conductor cable was made from

copper wires triple-coated with the

natural latex,

gutta-percha, clad with

tarred hemp.[2] Eighteen

iron wires, wound in a close

spiral at the peripherey, added

mechanical strength.[2]

The cable laying was completed in August, 1858, but the cable quickly deteriorated, and it was useless by September 18, 1858.[2] Various factors, including the

American Civil War, discouraged another attempt until 1865, when that cable broke during placement.[2] Another attempt, this time successful, was made the next year by the

SS Great Eastern.

The SS Great Eastern, a vessel of nearly 18 ton's

weight and 211

meters length, was the largest vessel at that time.[2] It sailed from

Valentia Island, Ireland, to

Trinity Bay, Newfoundland, Canada, laying about 4,000

kilometers (2485

miles) of cable.[2]

Engineers had learned from previous failures, and the new cable was far more rugged, weighing 1,014

kilograms per kilometer.[2] The copper wires were three times larger in

cross-section than those of the 1858 attempt, and they were coated with an improved

insulator consisting of

Chatterton's compound with gutta-percha. A spiral of steel wires added stength, just as in the previous cables.[2]

Final connection was made at

Heart's Content, Newfoundland, on July 27, 1866. The Great Eastern then returned to the Atlantic, where engineers successfully retrieved the broken ends of the 1865 cable and spliced them together, giving the world two transatlantic cables in a single year.[2]

Since the

capital cost of these cables was large, it was expensive to send a transatlantic message. The inital price was $10/

word, with a ten word minimum ($100).[2] A $100 is equivalent to $1,500 in

today's money. Because of this high price, only 5% of the potential

data bandwidth was used, so the price was reduced to about half, and

revenues increased.[2] Still, only wealthy customers, such as

newspapers, used the service, and it led to the formation of

United Press International that shared stories among many newspapers.[2]

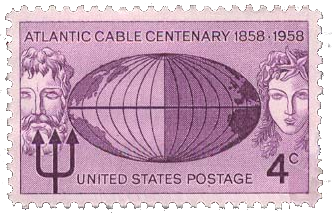

As mentioned in my primary reference to the 1865 cable, an article by

Robert Colburn, a

research coordinator at the

IEEE History Center,[2] the transatlantic cable has been recognized by two

IEEE Milestones. The first milestone was the Heart's Content terminal, recognized in 1985. The second milestone, in 2000, recognized the terminal sites at Ireland, Valentia Island,

Ballinskelligs, and

Waterville.[2]

References:

- Martin Chaplin, "Water and Microwaves," London South Bank University Web Site, December 18, 2015.

- Robert Colburn, "First Successful Transatlantic Telegraph Cable Celebrates 150th Anniversary," The Institute, IEEE, July 11, 2017.

- Lynden A. Jackson, "Submarine communication cable including optical fibres within an electrically conductive tube, US Patent No. 4,278,835, July 14, 1981.