Terpene

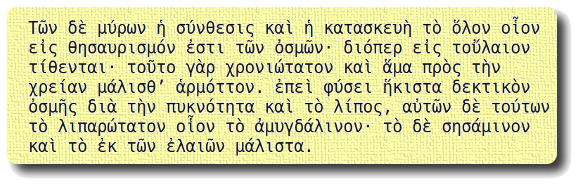

May 15, 2017 While modern man is generally concerned about his body odor, it appears that prehistoric man was not. Flowers would have been an abundant natural source of pleasant fragrance for primitive man. There is evidence that Neanderthals adorned themselves with bird feathers,[1] but they do not seem to have adorned themselves with flowers. There is evidence, however, of the use of flowers in prehistoric burials.[2] As civilization progressed, so did concerns about body odor. The ancient Greeks had developed a perfume industry at least as far back as the 4th century BC. Theophrastus (c. 371 - c. 287 BC), whose mineralogy treatise, "On Stones (Περι λιθων)," was mentioned in several articles on this blog (Pyroelectric Energy Harvesting, October 15, 2010, Rise and Fall of Coal, February 4, 2016, and Triboelectric Generators, February 8, 2016), described the perfumer's art in another short treatise on odors. Theophrastus succeeded Aristotle as leader of the Peripatetic school; and, like Aristotle, he wrote in many subject areas. Theophrastus wrote a lengthy treatise on botany, Enquiry into Plants (Περι φυτων ιστορια, Historia Plantarum), so he is often called the "father of botany." On Odors is usually placed as an appendix to the Enquiry into Plants.[3-4] On Odors describes the perfumers' secrets of his age (see figure). |

| A portion of Theophrastus', "On Odors," that discusses the oil extraction of fragrant compounds. "Now the composition and preparation of perfumes aim entirely, one may say, at making the odours last. That is why men make oil the vehicle of them, since it keeps a very long time and also is most convenient for use. By nature indeed oil is not at all well suited to take in an odour, because of its close and greasy character: and of particular oils this is specially true of the most viscous, such as almond-oil, while sesame-oil and olive-oil are the least receptive of all." (Original Greek and English translation from Theophrastus, "De odoribus (Concerning Odours)," vol. II of Loeb Classical Library edition of the Enquiry into Plants, 1926.)[3] |

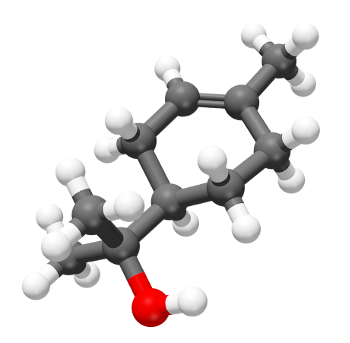

| α-Terpineol Alpha-Terpineol has a lilac scent. Although it's used as a fragrance in products such as soap, I used this compound as part of the electrolyte mixture in an electrochemical process. (Via Wikimedia Commons.) |

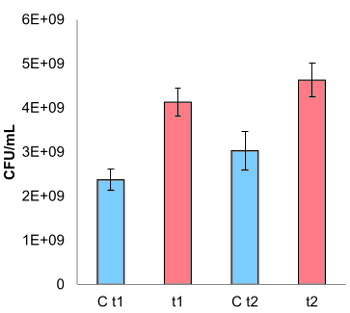

"We have known for some time that plants and insects use terpenes to communicate with each other. But we've only just begun to realize that it's actually much wider. There is a much larger group of 'Terpene-speakers': micro-organisms... Serratia, a soil bacterium, can 'smell' the fragrant terpenes produced by Fusarium, a plant pathogenic fungus. It responds by becoming motile and producing a terpene of its own."[7]

| Fungal VOC effect on bacterial growth. Controls (blue) and specimens (red) after 48 hours (t1) and 72 hours (t2) exposure. (Fig. 1(b) of ref. 6, modified, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license)[6] |

References:

- Clive Finlayson, Kimberly Brown, Ruth Blasco, Jordi Rosell, Juan José Negro, Gary R. Bortolotti, Geraldine Finlayson, Antonio Sánchez Marco, Francisco Giles Pacheco, Joaquín Rodríguez Vidal, José S. Carrión, Darren A. Fa, and José M. Rodríguez Llanes, "Birds of a Feather: Neanderthal Exploitation of Raptors and Corvids," PLOS ONE, vol. 7, no. 10, Article no. 0045927, October 12, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0045927. This is an open access publication with a PDF file available here.

- Brian F. Byrd and Christopher M. Monahan, "Death, Mortuary Ritual, and Natufian Social Structure," Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. vol. 14, no. 3 (September, 1995), pp. 251-287, https://doi.org/10.1006/jaar.1995.1014.

- Theophrastus, "De odoribus (Concerning Odours)," vol. II of the Loeb Classical Library edition of the Enquiry into Plants, 1926, via the University of Chicago.

- Theophrastus, "Enquiry into plants and minor works on odours and weather signs," Greek with an English translation by Sir Arthur Hort, vol. 2, W. Heinemann (London, 1916), pp. 524.

- D.H. Pybus, and C.S. Sell, "The Chemistry of Fragrances," Chapter 4, Royal Society of Chemistry, December 31, 1999, pp. 276, ISBN-13: 978-0854045280.

- Ruth Schmidt, Victor de Jager, Daniela Zühlke, Christian Wolff, Jörg Bernhardt, Katarina Cankar, Jules Beekwilder, Wilfred van Ijcken, Frank Sleutels, Wietse de Boer, Katharina Riedel and Paolina Garbeva, "Fungal volatile compounds induce production of the secondary metabolite Sodorifen in Serratia plymuthica PRI-2C," Scientific Reports, vol. 7, Article no. 862, April 13, 2017, doi:10.1038/s41598-017-00893-3. This is an open access article with a PDF file at the same link.

- The world's most spoken language is...Terpene, Netherlands Institute of Ecology Press Release, April 13, 2017.