Robot Musicians

July 10, 2017

Many

decades ago, long before the advent of

ubiquitous computing and today's

miraculous artificial intelligence systems, I was a

freshman college student taking an "introduction to music"

course. The

textbook, "The Enjoyment of Music," was written by Joseph Machlis, a

professor of

music at

Queens College of the City University of New York. Although Machlis is

deceased, the book is still revised by a team of

authors.[1]

As could be expected from a book intended for

non-musicians, the book was light on

music theory and heavy on

music history. One course requirement was to write a

review of an

orchestral concert, and another was to write a

term paper. I wrote mine on

electronic music. At that time, electronic music was generally produced by

analog means, such as modification of

recorded natural sounds (

Musique concrète). In that age of

engineering students carrying boxes of

punched cards around

campus, I

speculated in my paper that

computers would one day

compose their own music.

Quite a few years after that, in 1985, I was in conversation with the

husband of my

son's piano teacher. He was a noted

violinist, I was

experimenting with

computer music, and we had a lively conversation about musicians eventually being replaced by

automation. He argued that a machine couldn't reproduce the special

acoustic nuances of

professional musicians; and I, having taken a short course in

neural networks, said that a machine could do just as well when given enough examples.

Automation of music was an important topic at that time, since orchestras for

Broadway musicals were shrinking. The culprit was the

electronic music synthesizer, by which a single musician could replace an entire orchestral section, such as

strings or

brass. The

musician's union was quite upset about this, and this was a

harbinger of what is now happening in many other professions.[2-3]

Translating

pseudorandom numbers into

musical notes will produce something worse than any

twelve-tone composition, but there's one simple technique that produces adequate results. A

Markov chain produces random samples that depend on their recent history, and it can produce random samples with a particular

probability distribution. One popular application of Markov chains is the generation of "

travesty texts," texts that mimic the qualities of particular source material.

The prolific

Brian Hayes published such a generator in a 1983 article in

Scientific American.[4] At the time of his writing, Hayes did not know that he was building on some obscure work by the

Russian mathematician,

Andrei Markov (1856-1922).[5-6] The Markov chain text generation

algorithm, which could be implemented on a 1983

personal computer, can also be applied to musical composition with great success. As they say, "one note follows another," and this technique proves it.

Much later,

David Cope developed advanced techniques for computer music generation.[7-8] An extended list of

references to his papers on his concept of "Recombinant Music Composition" can be found in his

2010 US patent no. 7,696,426, Recombinant Music Composition Algorithm and Method of Using the Same.[9] As the name implies, the technique uses

genetic programming to generate and evaluate musical phrases based on a seed.[7]

In the production of music, we have the

composer, soon to be automated in some cases, then the musicians. Why not automate the musicians, also, to have an instantaneous performance concurrent with the instantaneous composition? While synthesized orchestral instruments have performed computer compositions, this has rarely been done concurrently. While

physical pianos have been modified to perform

digital music, there's not a

robot at a seat banging the

keys with mechanical

fingers.

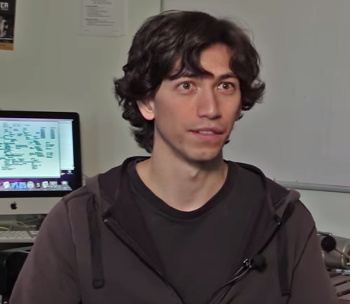

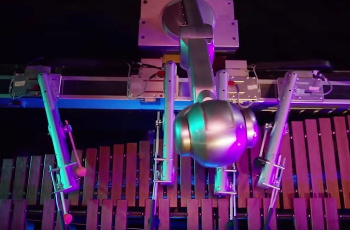

Now,

researchers at the

Georgia Institute of Technology (Atlanta, Georgia) have created, Shimon, a robot

marimba player with four arms that composes its own music and can listen and

improvise alongside human performers.[10-11] Shimon was created over the course of seven years by

Mason Bretan, a

Ph.D. candidate under

advisor,

Gil Weinberg, director of

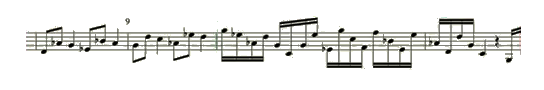

Georgia Tech's Center for Music Technology.[11] Shimon uses a

deep learning neural network that takes as an input a two-four

measure-long seed

melody. The neural network has been trained on nearly 5,000 compositions from such composers as

Beethoven,

Lady Gaga, and

Miles Davis.[10-11]

This is the first time a robot based on deep learning has created music, including

harmonies and

chords. Says Breton,

"Once Shimon learns the four measures we provide, it creates its own sequence of concepts and composes its own piece... Shimon's compositions represent how music sounds and looks when a robot uses deep neural networks to learn everything it knows about music from millions of human-made segments."[11]

As for all neural networks, Shimon's music is very similar to its

training set. If it were fed data from just one composer, its music would sound like another composition of that composer. However, shorter seeds will lead to greater variation in the output, so the music will deviate from the composer's

repertoire to some extent.[10] Also, the level of

look-back is important, and it can range from as few as two measures, to as many as sixteen measures.[10]

Shimon had its

debut at the the

Consumer Electronic Show, but only as a

video clip. It will have its first live performance at the

Aspen Ideas Festival, June 22-July 1, 2017, in

Aspen, Colorado.[11] Students in Weinberg's lab have also created a robotic "third arm" for

drummers.[11] That sounds like an interesting variation on the

old-time one-man band.

References:

- Kristine Forney, Andrew Dell'Antonio, and Joseph Machlis, "The Enjoyment of Music (Shorter 12th Edition," Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company, 504 pp., ISBN-13: 978-0393936384 (via Amazon).

- Alex Witchel, "Replaced By Synthesizer, 'Grand Hotel' Musicians Protest," Chicago Tribune, September 19, 1991.

- Ernio Hernandez, "Musicians Ready to Rally Against Use of "Virtual Orchestra" Machine Off-Broadway," Playbill, April 12, 2004.

- Brian Hayes, "Computer Recreations: A progress report on the fine art of turning literature into drivel." Scientific American, vol. 249, no. 5 (November 1983), pp. 18-28.

- A.A. Markov, "An example of statistical investigation of the text Eugene Onegin concerning the connection of samples in chains," Bulletin of the Imperial Academy of Sciences of St. Petersburg, vol. 7, no. 3 (1913), pp. 153-162. English translation by Alexander Y. Nitussov, Lioudmila Voropai, Gloria Custance and David Link, Science in Context, vol. 19, no. 4 (2006), pp. 591-600, doi:10.1017/S0269889706001074. A PDF file can be found here.

- Brian Hayes, "First Links in the Markov Chain," American Scientist, vol. 101, no. 2 (March–April, 2013), pp. 92-97 .

- Philip Ball, "Artificial music: The computers that create melodies," BBC, August 8 2014.

- David Cope - Emmy Beethoven 2, YouTube Video by David Cope, August 12, 2012.

- David H. Cope, "Recombinant music composition algorithm and method of using the same," US Patent No. 7,696,426, April 13, 2010.

- Evan Ackerman, "Four-Armed Marimba Robot Uses Deep Learning to Compose Its Own Music," IEEE Spectrum, June 14, 2017.

- Jason Maderer, "Robot Uses Deep Learning and Big Data to Write and Play its Own Music," Georgia Institute of Technology Press release, June 13, 2017.

- Robot Composes, Plays Own Music Using Deep Learning, YouTube Video by Georgia Tech, June 14, 2017.

- Robot Composes, Plays Own Music Using Deep Learning (with notes), YouTube Video by Georgia Tech, June 14, 2017.