Physics, Math, and Sociology

June 8, 2017

Physicists consider themselves to be at the top of the

scientific food chain. This is verified by the fact that the majority of the nineteen

Presidential Science Advisors were physicists. Notable physicist-advisors include

Isidor Rabi (1898-1988),

David Allan Bromley (1926-2005),

Frank Press (b. 1924), and

Guyford Stever (1916-2010).

A noted

chemist,

George Kistiakowsky (1900-1982), somehow broke into these ranks. The first Science Advisor,

Vannevar Bush (1890-1974), was an

electrical engineer, as was

Oliver Buckley (1887-1959). I wrote about Vannevar Bush and Guyford Stever in previous articles (

Basic Research, October 22, 2010, and

H. Guyford Stever, May 18, 2011).

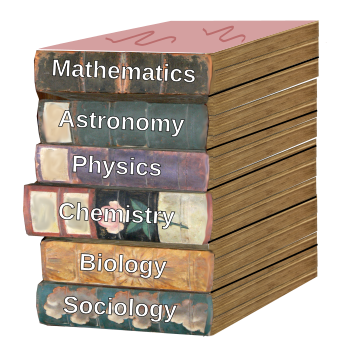

Auguste Comte (1798-1857), considered by many to be the first

philosopher of science, actually placed physics somewhat in the middle of the sciences, with

astronomy and

mathematics holding the places of most esteem (see figure).[1] His ranking placed the more

phenomenological disciplines towards the bottom, and the more fundamental disciplines at the top. Comte considered the topmost sciences to be more advanced, with a progression of

complexity from the top to the bottom. For example, the

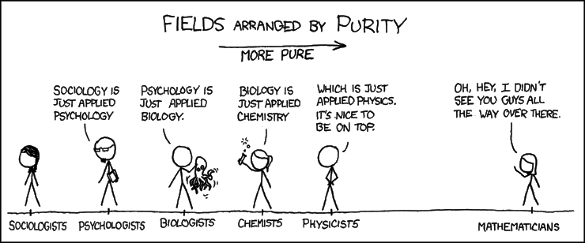

laws of chemistry depend on the laws of physics, and not the other way around. This ranking, with astronomy lumped together with physics, persists today, as the following

cartoon illustrates.

Physicists use a lot of mathematics, and most would agree with Comte's scheme of ranking mathematics as more fundamental than physics. This, however, presumes that physics and mathematics are both

research disciplines, so we arrive at the very fundamental question of whether mathematics is

discovered, or

invented.[2]

Plato, and contemporary mathematician,

Roger Penrose, believe that mathematics is discovered, as do I, so I'm in good company.

Pi, the

ratio of the

circumference to the

diameter of a

circle, is found in many fundamental

equations of physics, so it appears that pi has a physical

reality independent of an observer. If you're a mathematician in the discovery camp, you do mathematics by looking for solutions that already exist. The mathematics is

somewhere, waiting to be discovered; that is, the pure

idea has an existence, which is a Platonist concept. Those mathematicians in the invention camp believe that mathematics is just another

intellectual product of

human culture.

An interesting

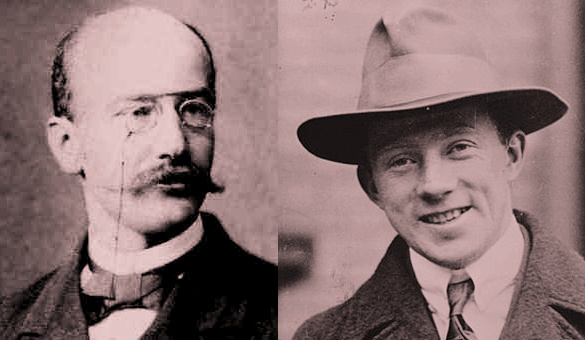

anecdote about the attitude of mathematicians to physics involves

Werner Heisenberg (1901-1976), who was awarded the 1932

Nobel Prize in Physics "for the creation of

quantum mechanics." Heisenberg had initially wanted to become a mathematician, so he interviewed to become a

student of

Ferdinand von Lindemann (1852-1939).

Lindemann, who was famous for proving that pi was a

transcendental number, was 68, somewhat

deaf, close to

retirement, and the

quintessential grumpy old mathematician. When Heisenberg told him that he had read

Hermann Weyl's, "

Raum, Zeit, Materie" (Space, Time, Matter),[3] Lindemann told him that his mathematics career was hopelessly contaminated. Heisenberg ended up as a student of

theoretical physicist,

Arnold Sommerfeld, who also had provoked Lindemann's

disdain.[4]

The wide gap between physics and sociology has been bridged; and, like most bridges, the

traffic has been bidirectional, in sociology investigating physics, and physics advancing sociology. The social structure of the occasional isolated

Amazon tribe might be interesting, but how much more interesting is the culture of nearly a million physicists?[5] This is the realm of the field of the

sociology of scientific knowledge. Prominent sociologists in this field include

Paul Feyerabend (1924-1994),

Thomas Kuhn (1922-1996), and

Derek John de Solla Price (1922-1983). I wrote about Kuhn in a previous article (

Fifty Years of Paradigm Shifting, February 25, 2013. As one example, sociologists embedded themselves at

CERN during the early years of the

Large Hadron Collider, a 10,000-person physics project.[6]

In the other direction we have

social physics in which physicists use their tools to develop a better understanding of the

human condition. Comte, whom I mentioned above, believed that social physics could discover the

natural laws of social culture.

Belgian statistician,

Adolphe Quetelet, wrote a 1835 book, "Sur l'homme et le développement de ses facultés, ou Essai de physique sociale" (Essay on Social Physics: Man and the Development of his Faculties), in which he proposed the application of

statistics to sociology. He was essentially looking for the

root causes of cultural attributes such as

crime. He also proposed the idea of the

average man who sits atop the

bell curve.

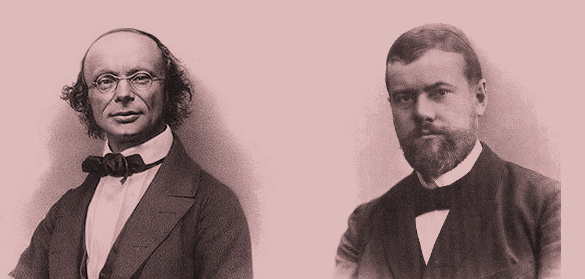

|

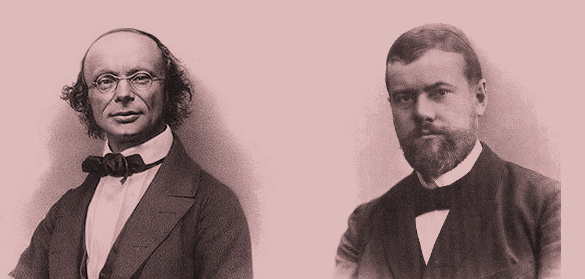

| A tale of two Webers. Left, Wilhelm Eduard Weber (1804-1891), and right, Maximilian Karl "Max" Weber (1864-1920). Wilhelm Weber was a German physicist who co-invented the electric telegraph with colleague, Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777-1855). He was also the first to use the letter "c" to denote the speed of light in an 1856 paper co-authored with Rudolf Kohlrausch (1809-1858). The unit of magnetic flux, the weber, is named after him. Max Weber, one of the first sociologists, proposed that there are multiple causes for any outcome. He is best known for conflation of the Protestant work ethic, the rise of capitalism, and the institution of the rational nation-state. (Left image and right image via Wikimedia Commons.) |

The prolific science writer,

Philip Ball, has written a book that demonstrates how

systems theory can elucidate such social phenomena as

traffic flow,

economics, and the structure of

cities.[7] Social physics is now enabled by "

big data," harvested from various

Internet sources, that combines data from such human activities as

Facebook posting,

web browsing history, and

credit card purchases. A recent example of a social physics paper can be found in ref. 8.[8] If you look at the lower right-hand corner of this page, you'll see that

Tikalon supports the

Electronic Frontier Foundation in putting limits on how much of our personal data is shared.

Of course, there's still much about sociology that makes it a far different science than physics. Any cursory examination of introductory

textbooks in the two fields will show a vast difference in the number of

references - About a hundred for physics, versus nearly a thousand in sociology, with physics references going back many years, and the sociology references much more contemporary.[9] Also, physics textbooks will have about the same content from one to another, while sociology textbooks are quite different from one

decade to the next.[9] Physics speaks of fundamental laws, while sociology is always searching for its path.

References:

- Auguste Comte, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, October 16, 2014.

- Julie Rehmeyer, "Math Trek-Still debating with Plato," Science News, April 25, 2008.

- Hermann Weyl, "Raum, Zeit, Materie - Vorlesungen über allgemeine Relativitätstheorie," J. Springer (Berlin, 1919), 296 pp., via archive.org.

- David Lindley, "Uncertainty," Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, February 12, 2008, p. 79, via Google Books.

- Charles Day, "One million physicists," Physics Today, April 17, 2015, DOI:10.1063/PT.5.010310.

- Zeeya Merali, "The Large Human Collider," Nature, vol. 464, March 24, 2010, pp. 482-484, doi:10.1038/464482a.

- Philip Ball, "Why Society is a Complex Matter," Springer, June 9, 2012, ISBN 978-3-642-28999-6.

- Matjaz Perc, Jillian J. Jordan, David G. Rand, Zhen Wang, Stefano Boccaletti, and Attila Szolnoki, "Statistical physics of human cooperation," arXiv, May 19, 2017

- Stephen Cole, "The Hierarchy of the Sciences?," American Journal of Sociology, vol. 89, no. 1 (July, 1983), pp 111-139, https://doi.org/10.1086/227835.