The Wisdom of Composite Crowds

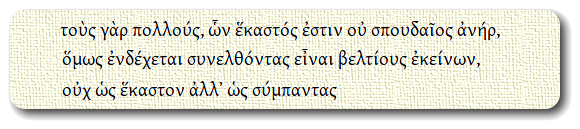

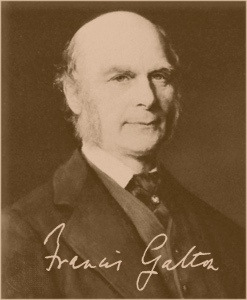

April 27, 2017 Physical scientists are able to control their experiments quite closely. Chemists will choose pure materials for their reactions, and physicists will undertake measurements under precise temperature, pressure, and other conditions. Experiments in many of the life sciences are seldom as precise, since they're conducted on organisms that are not precisely equivalent from one individual to another. It's only by doing experiments on many organisms, and analysis of the data by statistics, that those disciplines can transcend what Rutherford called "stamp collecting."[1] Statistics are important when we venture away from science and into the realm of opinion; but, as the performance of some opinion polls for the last US Presidential election reminds us, the methodology can be tricky. However, it appears the the composite opinion of large numbers of properly selected people will give us a better answer to a question that of a few individuals. While Aristotle (384 BC-322 BC) alludes to the idea of the "wisdom of the crowd" in his Politics (see figure),[2] Victorian polymath, Francis Galton (1822-1911) was the first to apply this concept statistically. In 1906, Galton observed a contest at a livestock fair in which 800 visitors guessed the weight of meat that would be produced by a particular ox. |

| "For it is possible that the many, though not individually good men, yet when they come together may be better, not individually but collectively, than those who are so..."(Aristotle, Politics, Book III, Section 1281a41-1281b1, via the Tufts University Perseus Digital Library.[2]) |

| Photograph of Francis Galton (1822-1911), with signature. Galton was a Victorian polymath best known to scientists as the originator of the statistical concept of correlation. He is known to most others for coining the term, eugenics, for a concept that goes back to Plato. (image source and signature source, via Wikimedia Commons.) |

| Educated guessing. Scientists make educated guesses, so their approach to guessing the number of objects in a jar differs from that of most people. A random packing of spheres will occupy about 2/3 of the volume of a space, while ellipsoidal objects, such as the olives shown, will pack about 3/4 of the volume. I discussed packing in a previous article (Packing, November 30, 2010). (Wikimedia Commons image.) |

| 1. | Japan has the world's highest life expectancy. |

| 2. | The Nile River is more than double the length of the Volga. |

| 3. | Portuguese is the official language of Mozambique. |

| 4. | Avogadro's constant is greater than Planck's constant. |

| 5. | The currency of Switzerland is the Euro. |

| 6. | Abkhazia is a disputed territory in Georgia. |

| 7. | The chemical symbol for Tin is Sn. |

| 8. | The Iron Age comes after the Bronze Age. |

| 9. | Schuyler Colfax was Abraham Lincoln's Vice President. |

| 10. | The longest bone in the human body is the femur. |

References:

- "All science is either physics or stamp collecting," Ernest Rutherford, as quoted by J. B. Birks, via Wikiquote.

- Aristotle's Politica (in Greek), W. D. Ross, Ed., Clarendon Press (Oxford, 1957) via the Tufts University Perseus Digital Library, Gregory R. Crane, Ed.. English translation: Aristotle in 23 Volumes, Vol. 21, H. Rackham, Trans.,Harvard University Press (Cambridge, MA, 1944).

- Stefan Krause, Richard James, Jolyon J. Faria, Graeme D. Ruxton and Jens Krause, "Swarm intelligence in humans: diversity can trump ability," Animal Behaviour, vol. 81, no. 5 (May, 2011), pp. 941-948.

- Study finds that diversity can trump ability, University of Bath Press Release, April 21, 2011.

- Research Highlights-Behaviour: Diversity beats ability, Nature, vol. 472, no. 7343 (April 21, 2011) p. 263.

- Study finds that diversity can trump ability, Physorg, April 21, 2011.

- Joaquin Navajas, Tamara Niella, Gerry Garbulsky, Bahador Bahrami, and Mariano Sigman, "Deliberation increases the wisdom of crowds," arXiv, March 2, 2017.

- Drazen Prelec, H. Sebastian Seung, and John McCoy, "A solution to the single-question crowd wisdom problem," Nature, vol. 541, no. 7638 (January 26, 2017), pp. 532-535, doi:10.1038/nature21054.

- Supplementary information for ref. 8 (PDF file).

- Peter Dizikes, "Better wisdom from crowds," MIT Press Release, January 25, 2017.