Eugene Garfield (1925-2017)

April 3, 2017

While many

theoreticians might object to the statement, progress in

science comes principally as a result of advances in

instrumentation. Examples of this abound in the

history of science.

Galileo's telescope caused a

revolution in

astronomy. The development of the

vacuum tube enabled a

plethora of

electronic measurement equipment subsequently improved by the

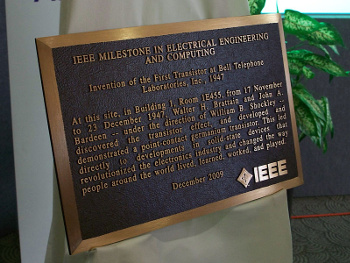

invention of the

transistor. For current examples, we have the $10 billion

Large Hadron Collider, and the

Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory that gives us great science for less than a $billion.

The

computer is one

scientific tool that's greatly enhanced the practice of all scientific

disciplines. Aside from the incorporation of computers into instrumentation for

automated analysis and

data acquisition, computers make

publication of

scientific papers much easier.

My generation was the last

generation to do

least-squares curve fitting of our

data by hand.

Publication before computers was a chore, with

manuscripts created on a

typewriter, the

graphs hand drawn using

India ink, and the

photographs produced in a

darkroom using a primitive

chemical imaging method involving

colloidal silver halide. After

peer review, manuscripts were revised, retyped, and accepted by the publisher, who then undertook the tedious process of rendering the text and graphics for

mechanical printing. Since errors were always expected in this tedious process, especially in the proper rendering of

mathematical equations, the publisher would send

page proofs for correction.

Today,

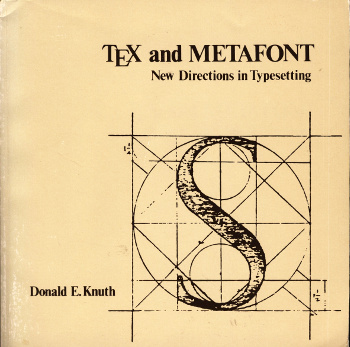

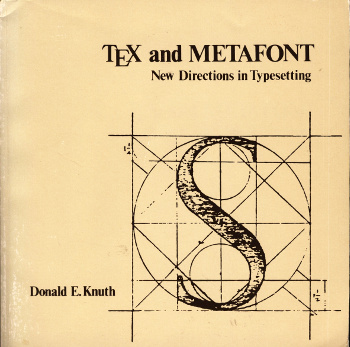

document preparation programs, such as the

LaTeX distribution of

Don Knuth's TeX, allow an

author to

eliminate the middle man, so to speak, to give him full control of his paper. Not only that, but the

Internet has allowed a more rapid distribution of scientific papers, and

open access options allow any interested reader to read these papers at no charge.

| Cover of Don Knuth's 1979 book, "TeX and METAFONT: New Directions in Typesetting."[1]

Metafont is a vector font description language.

(Scan of my copy.) |

Before the Internet, the only way to read scientific papers was the get a

journal subscription, typically through membership in a

scientific society, find them at a

university library with enough funding to pay for an expensive institutional subscription, or get a

reprint from one of the authors. While the later option generally got you a copy at just the cost of a

postcard's postage, you still needed to identify the papers that captured your interest.

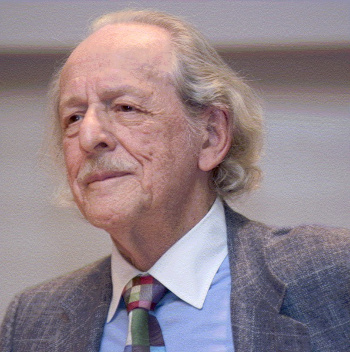

Eugene Garfield, who died on February 26, 2017, at age 91, simplified this process for many

scientists by creating

Current Contents.[2-3]

Current Contents, of which I was an avid weekly reader, was first published in 1977. Its simple concept, direct images of the recent

tables of contents of the most important scientific journals, along with the addresses of paper authors, allowed an easy means of securing reprints of papers. Current Contents included a weekly one-page summary of a so-called Citation Classic, one of the most cited papers in the scientific literature.[4]

Current Contents followed by more than a

decade another of Garfield's publications, the 1964

Science Citation Index, a directory of how frequently articles in the scientific literature had been

cited. This, of course, is a measure of the importance of the work, and such a ranking was often used by universities in their academic promotions, such as

tenure. One interesting aspect of this is that papers describing

analytical techniques have many citations, although they would be classified as "

normal science."[5]

The paper with the most citations (more than 300,000) is a paper by

biochemist,

Oliver Lowry (1910-1996), on an

assay for the amount of protein in solution.[6] Lowry was encouraged to publish the assay by his

colleague and eventual

Nobel laureate,

Earl Sutherland (1915-1974), who complained about always referring to "an unpublished method of Lowry."[7]

Eugene Garfield was born on September 16, 1925, in

New York City. First a

chemist, having obtained a

BS degree in

chemistry from

Columbia University in 1949, he obtained a 1954

master's degree, also from Columbia University, in

library science.[2] He continued for a

Ph.D. in

structural linguistics at the

University of Pennsylvania in 1961,[3] albeit on a chemical topic, an

algorithm for

translating chemical nomenclature into

chemical formulas.[8]

Garfield, who preferred to be known as an

information engineer or

information scientist, rather than a

librarian, was assuredly an

entrepreneur.[2] He founded the

Institute for Scientific Information (ISI) in

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1955.[2] Long before ubiquitous computing made

databases common, he assembled scientific information into a readily accessible form that aided study and diminished duplicate research.[2] His

journal impact factor was both important, and problematic. It was used at ISI to determine which journals should be indexed, but it became a metric for academic ranking, a practice that Garfield disliked.[3]

Garfield founded

The Scientist in 1986, a publication he considered a "

trade magazine" for working scientists.[2-3] The Scientist published science news, and also articles on

policy and

ethics that are not found in scientific journals.[3] This magazine continues today, thirty years after its founding.[3] ISI was sold in 1988 for $24 million, and it was sold, six years later, to the

Thomson Corporation for $210 million.[3] It is now owned by

Clarivate Analytics.[2]

At his death, Meher Garfield, Garfield's

wife, said that he was mindful of his humble beginnings, he never became arrogant in his success, and he thought of his

employees as his

extended family.[3] He was a supporter of the Philadelphia

poverty and

homelessness advocacy group,

Project HOME.[2] In his spare time, he enjoyed reading and

windsurfing.[2]

Vitek Tracz, a former co-owner of The Scientist, is quoted on The Scientist web site as saying,

"Everything he did, he was ahead of everybody in so many ways...He was a genius of a very special type. Not only because he had this incredible imagination and brain, but he had incredible tenacity and courage."[3]

References:

- Donald E. Knuth, "TeX and METAFONT: New Directions in Typesetting," The American Mathematical Society and Digital Press, 1979, 105 pp., ISBN: 0-932376-02-9.

- Bonnie L. Cook, "Eugene Garfield, 91, created an indexing system for scientific knowledge," philly.com, March 13, 2017.

- Scientometrics Pioneer Eugene Garfield Dies, The Scientist, February 27, 2017.

- Eugene Garfield, "Short History of Citation Classics Commentaries," Garfield Library, University of Pennsylvania.

- Richard Van Noorden, Brendan Maher, and Regina Nuzzo, "The top 100 papers," Nature, October 29, 2014.

- O. H. Lowry, N. J. Rosebrough, A. L. Farr, and R. J. Randall, "Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent," J. Biol. Chem., vol. 193 (November 1, 1951), pp. 265-275.

- Nicole Kresge, Robert D. Simoni and Robert L. Hill, "The Most Highly Cited Paper in Publishing History: Protein Determination by Oliver H. Lowry," The Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 208, no. 28 (July 15, 2005), p. e25.

- Eugene Garfield, "An Algorithm for Translating Chemical Names to Molecular Formulas," Journal of Chemical Documentation, vol. 2, no. 3 (July 1962), pp. 177-179, DOI: 10.1021/c160006a021