Stellar Classification

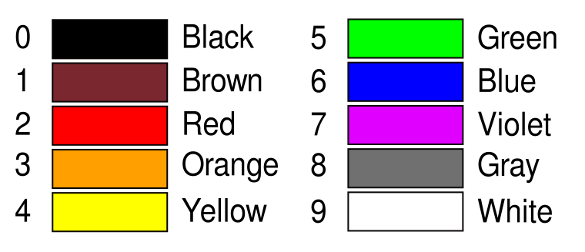

June 9, 2016 As everyone knows, the sciences have traditionally been male-dominated professions. Worse than that, scientists and engineers have a history of being downright misogynist. One glaring example of my generation is the mnemonic for electronic component color code. In those days before rapid printing of fine pitch numeric characters on odd-shaped objects, resistance, capacitance, and inductance values were specified by bands of color. The colors, black, brown, red, orange, yellow, green, blue, violet, gray, and white, represented the numbers zero-nine. The mnemonic I learned in the dark corner of the lab was "Bad boys rape our young girls but violet gives willingly." Violet is still a common name today, ranking 77th as a girl's name in the current decade.[1] |

| The electronic component color code, used for resistors, capacitors, and inductors. (Created using Inkscape.) |

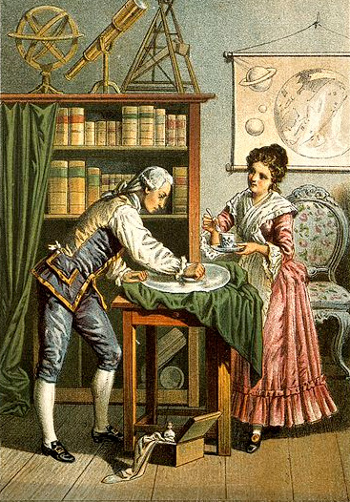

| William Herschel, discoverer of the planet, Uranus, and his sister, Caroline. Herschel is shown polishing a telescope mirror, assisted by Caroline. Caroline Herschel was awarded a gold medal from the Royal Astronomical Society, and she received a small salary from King George III. An 1896 lithograph from the Wellcome Library, via Wikimedia Commons.) |

"A straight line can readily be drawn among each of the two series of points corresponding to the maxima and minima, thus showing that there is a simple relation between the brightness of the variables and their periods... Since the variables are probably at nearly the same distance from the Earth, their periods are apparently associated with their actual emission of light..."Leavitt graduated from Radcliffe College, Harvard's female outpost, in 1893, and she joined the Harvard College Observatory. Her title there was "computer," and her work was to translate the images of stars on photographic plates to useful data. That's how her Cepheid variable discovery was enabled, a discovery that allowed Hubble to relate galactic redshift to their distance from the Earth, a relationship now known as Hubble's law.

|

| "A woman's work is never done." American astronomer, Henrietta Swan Leavitt (1868-1921). (Photograph from the Emilio Segrè Visual Archives of the American Institute of Physics, via Wikimedia Commons.) |

| A circa 1879 photograph of Sarah Frances Whiting (1847-1927). When Wilhelm Röntgen discovered X-rays in 1895, Whiting configured an old Crookes tube to take some of the first radiographs. These were of coins in a purse, and bones through flesh.[3] (A Wellesley College photograph, via Wikimedia Commons.) |

| A 1922 portrait of Annie Jump Cannon (1863-1941). (Portrait appearing in the New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper, via Wikimedia Commons.) |

| The 56 kilometer diameter Cannon Crater, named after Annie Jump Cannon, is located on the Moon at 19.9°N 81.4°E. (A Lunar Orbiter 4 image, via Wikimedia Commons.) |

References:

- Baby Names for the 2010 Decade, United States Social Security Administration Web Site.

- Dan Malerbo, "Let's talk about science: development of star classification," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 19, 2016.

- Annie J. Cannon, "Sarah Frances Whiting," Science, vol. 66, no. 1714 (November 4, 1927), pp. 417-418, DOI: 10.1126/science.66.1714.417.