Granular Entropy

March 14, 2016

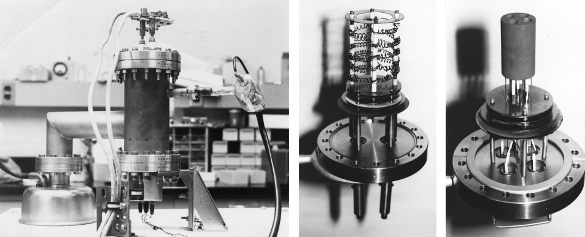

For my

dissertation, many

decades ago, I measured the high

temperature reaction of

metals forming

alloys. To do this, I teamed with a

graduate student colleague to construct a high temperature

calorimeter. Fortunately, he was good at doing

mechanical things, like wrestling with

vacuum systems, while I had a talent for

electronics, so the system performed its intended task. Eventually, I was able to build a second system to increase

throughput (see figure).

In explaining one of his results, my colleague invoked

entropy. As we talked about this, I realized that I didn't know the relative importance of entropy in

thermodynamics. Sure, I knew all the

textbook equations from several

statistical mechanics and thermodynamics courses, but I had no idea whether entropy had a small or large affect on things such as the

heat of formation (a.k.a.,

enthalpy of formation) of a

compound.

The assess the importance of enthalpy, let's look at a simple process, the

evaporation of a

material such as

aluminum. Since

boiling is an

equilibrium phase transformation in which the

liquid and

gas phases coexist, the

Gibbs free energy change

ΔG of the transformation is zero,

where

ΔH is the

enthalpy of vaporization, and

ΔS is the

vaporization entropy. We can see that entropy is just as important as enthalpy, at least in this example of boiling, since the terms are equal.

Entropy is a strange property of matter that arises from the principle that objects can be arranged in different ways.

Students of

physics and

chemistry are familiar with

Boltzmann's entropy formula,

in which

S is the

entropy,

KB is the

Boltzmann constant (1.38062 x 10

-23 joule/

kelvin), and

Ω is the number of states accessible to a system.

The Boltzmann entropy formula is actually a simplification of the

Boltzmann-Gibbs entropy when every state has the same

probability pi; viz.,

Both of these equations define a maximum entropy, a consequence of the equal probability of stuffing an

atom or

molecule into any accessible state.

While we usually think of entropy in terms of atoms and molecules where their huge numbers give large entropy values, we can apply the entropy concept, also, to smaller assemblages of larger particles constrained in a

volume.

Granular materials have become an important

research area in physics, so the question arises as to what entropy value a handful of such

macroscopic scale particles might have. That's a question answered in a recent study by

chemists at the

University of Cambridge (Cambridge, United Kingdom).[1-2]

The press release for this research figuratively asks, "How many ways can you arrange 128

tennis balls (in a fixed volume)?" and the answer is the huge number 10

250. This number greatly exceeds the total number of

atoms in the

universe, which is

estimated to be 1080. The

packing is reminiscent of the

random packing of

oblate spheroids I discussed in an

earlier article (Packing, November 30, 2010).

The physics of granular materials has application to the understanding of the behavior of such materials as

soil,

sand, and

snow. Granular materials will only change their configuration after application of an external

force, and an understanding of their entropy could enable prediction of things such as

avalanches.[2] Says study

coauthor Stefano Martiniani of

St. John's College, Cambridge, "Granular materials themselves are the second most processed kind of material in the world after

water, and even the shape of the

surface of the Earth is defined by how they behave."[2]

Calculation of the configurational entropy of a granular system is so complex that it was never attempted for a system of more than about twenty particles.[2] The Cambridge team was able to increase this limit to 128 by building upon previous work.[3-4] An exhaustive

enumeration of particle states is not computationally tractable. Instead, the research team selected a small sample of configurations and calculated the

probability of their occurrence.[2] With this information, they were able to

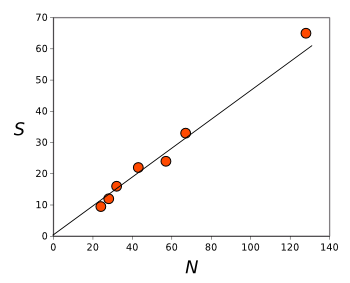

estimate the total configurational entropy (see figure).

| See a trend?

Configurational entropy as a function of system size N for three-dimensional jammed sphere packings.

The line is a linear fit of the data.

(Graphed using Gnumeric from data in ref. 1.[1]) |

This technique can be applied to other areas, including

machine learning, where it's useful to know all the different ways you can connect a system to process information.[2] As the authors state in the abstract of their paper, the technique "should be applicable to a wide range of other enumeration problems in

statistical physics,

string theory,

cosmology, and machine learning..."[1] Says Martiniani,

"Because our indirect approach relies on the observation of a small sample of all possible configurations, the answers it finds are only ever approximate, but the estimate is a very good one... By answering the problem we are opening up uncharted territory. This methodology could be used anywhere that people are trying to work out how many possible solutions to a problem you can find."[2]

References:

- Stefano Martiniani, K. Julian Schrenk, Jacob D. Stevenson, David J. Wales, and Daan Frenkel, "Turning intractable counting into sampling: Computing the configurational entropy of three-dimensional jammed packings," Phys. Rev. E, vol. 93, no. 1 (January, 2016), Document no. 012906, DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.93.012906.

- How many ways can you arrange 128 tennis balls? Researchers solve an apparently impossible problem, St. John's College, Cambridge, Press Release, January 27, 2016.

- Ning Xu, Daan Frenkel, and Andrea J. Liu, "Direct Determination of the Size of Basins of Attraction of Jammed Solids," Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 106, no. 24 (June 17, 2011), Document no. 245502.

- Daniel Asenjo, Fabien Paillusson, and Daan Frenkel, "Numerical Calculation of Granular Entropy," Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 112, no. 9 (March 7, 2014), Document no. 098002.