Coffee Acoustics and Espresso Foam

October 31, 2016

While

taste and

smell are the primary

senses used for

quality control in the

kitchen, the other senses are used as well. The sense of

touch is used when you depress the center of a

cake to test for doneness, and

sight to determine when you've entered the

Maillard reaction stage. And then there's

hearing.

If you listen beyond all the

machine noises, there are some useful kitchen

acoustics. Hearing is used in the kitchen when checking the progress of

baked bread, where a nice "thump" when tapping with a

spoon indicates doneness. The

temperature of

fry oil is often tested by the sound made when a

droplet of

batter is placed in the

pan. One beloved kitchen sound is the pop of

popcorn, with the initial pop and last pop signalling critical stages in the process.

A 2014 study, and recent follow-up

research, by

mechanical engineers at the

University of Texas at Austin looked at an acoustic method of quality control in

coffee roasting.[1-3] Just as popcorn pops,

coffee beans will crack while being roasted, and experienced coffee roasters listen for these sounds to monitor the roasting process. As we all know, and as I've discussed in a

recent article (The Future of Work, March 3, 2016), most

jobs will be

automated by

mid-century, and this research points to a way to either lighten a coffee roaster's workload, or put him out of work, depending on

management whim.

| As I've found, the key to good coffee is grinding your own beans, and storing bags of coffee beans in the freezer once they've been opened.

You don't need expensive beans - Supermarket beans make wonderful coffee. I mix these beans for my personal blend.

(Photo by author.) |

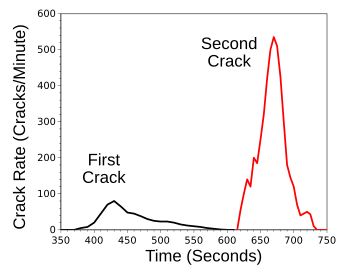

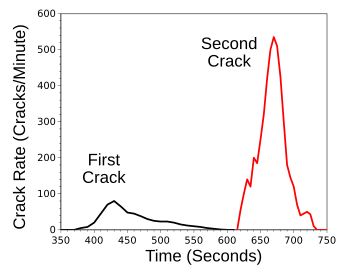

At the end of the coffee roasting process, two distinctive sounds are emitted; namely, a low

frequency, high

amplitude first crack, followed later by a higher frequency, lower amplitude

second crack. Also, the popping

rate of the

second crack is higher.[1-2] The

second crack signals the breakdown of

cellulose in the coffee beans, the release of oils, and a resultant darker roast.[3] If heating is stopped soon after the

first crack, the result is a highly

acid light roast. Somewhat longer heating after the

first crack allows

sugars to

caramelize.[3]

In the UTA

experiments, sounds were recorded from 62

first crack events and 241

second crack events while roasting

espresso blend beans in a home roaster.[3] It was found that the

first crack is 15% louder than the second, it occurs at about five

octaves lower frequency, with a popping rate just a fifth of the second. Some

audio analysis software could easily differentiate between the two.[2]

| Roasted coffee bean crack rate.

The second crack is easily distinguished.

(Graphed from data in fig. 3 of ref. 1 using Gnumeric.)[1] |

More than a billion servings of coffee are brewed each day worldwide, with the

United States responsible for about 400 million

cups. It's estimated that about a quarter of coffee consumed is

espresso. One reason for this is that it's the base coffee for such popular drinks as

caffè latte,

cappuccino,

caffè macchiato, and

caffè mocha. Espresso is typically made from

dark roast coffee having a considerable concentration of coffee oils.

Espresso is brewed by forcing

high pressure hot

water through finely ground and

compacted (tamped) coffee. This process results in a thick beverage of

dissolved and

solid materials, with the oils forming a

colloid. This colloid is evident by a surface

foam called the

crema, and experienced

baristas note the appearance of the crema for quality control of the espresso-making process.

In 2011,

Researchers from

Illycaffè S.p.A,

Trieste, Italy,

published a

review article on espresso coffee foam.[4] As they stated in their article, "Only recently, some aspects of the

Physics and

Chemistry behind the espresso coffee foam have attracted the attention of

scientists."[4] As they found,

carbon dioxide generated by roasting is an important factor, and the quality of the crema depends on the quantity of carbon dioxide generated and the influence of coffee

compounds.[4]

The importance of carbon dioxide is such that "espresso brewing can be described as "a quick way to transfer carbon dioxide from roasted and ground coffee to a small cup by means of hot water under pressure."[4] The important factors are therefore,[4]

• The carbon dioxide generated by roasting.

• Maintaining the carbon dioxide in the bean by proper

packaging.

• Maintaining the carbon dioxide in the ground coffee.

• Solubilizing the carbon dioxide in water.

• Releasing the carbon dioxide into the beverage.

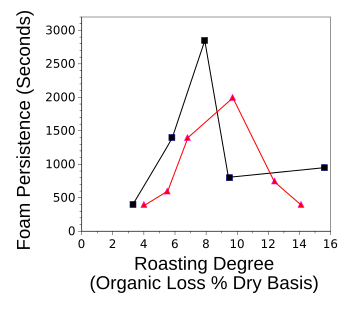

As the review

authors conclude, the foam

volume and

persistence (see figure) are the consequences of the carbon dioxide present in the coffee, with roasting and preparation aiding its release into the beverage. The carbon dioxide content and lipid content appear to be more relevant than coffee species for foam creation and foam stability.[4]

References:

- Preston S. Wilson, "Coffee roasting acoustics," J. Acoust. Soc. Am., vol. 135, no. 6 (June, 2014), article no. EL265, DOI: 10.1121/1.4874355. This is an open access publication with a PDF file available at the same link.

- Jay R. Johnson, Preston S Wilson, "Additional studies of the acoustics of coffee roasting," J. Acoust. Soc. Am., vol. 139, no. 4 (April, 2016), pp. 2165-2165, DOI: 10.1121/1.4950420.

- How to Roast Coffee by Ear, APS News, vol. 25, no. 8 (August/September, 2016). A PDF file is available here.

- Ernesto Illy and Luciano Navarini, "Neglected Food Bubbles: The Espresso Coffee Foam," Food Biophysics, vol. 6, no. 3 (September, 2011), pp. 335-348, DOI: 10.1007/s11483-011-9220-5. This is an open access publication with a PDF file available at the same link.