Caffeine-Resistant Bacteria

January 7, 2016

The

industrial revolution was

fueled by

coal, but our

information age is fueled by

coffee. We drink so much coffee that

environmental caffeine is a good indicator of

human presence. As the

earliest riser in our

research group, it was my responsibility to make the first pot of the

morning. I was happy to do this, since I took more care in

cleaning and

brewing than most others, perhaps because of my many years of working in a

materials laboratory. I also got to drink my coffee while it was still fresh.

During one of my visits to

Bell Labs in the 1970s, I was treated to one research group's coffee. They had taken a

scientific approach to the problem of keeping coffee fresh on the

hot plate by reasoning that

stale coffee was caused by

oxidation. As a consequence, they flowed

nitrogen gas, a convenient laboratory utility, into the open pot to displace the

oxygen. As I remember, this process worked well.

In the 1980s, as research laboratories became more

safety conscious, lab-brewed coffee was prohibited for some very obvious reasons, and we were forced to use the same coffee stations as our non-scientist

colleagues. Eventually, those

drip-style coffeemakers gave way to the single-serving types that are now common. As a coffee

connoisseur, I've always preferred coffee made using

vacuum coffee makers, or the

Chemex process.

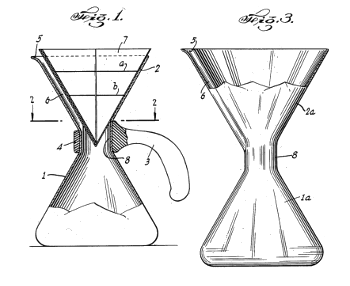

Chemex coffee, preferred by such "

manly men" as

Don Draper and

James Bond, was the

invention of the

German chemist,

Peter Schlumbohm. The Chemex process is essentially a drip coffee process using a thicker

filter paper than others. The Chemex coffee pot has its

conical filter holder and coffee pot integrated as one piece of

glass. At one time I used a variant process that utilized a large plastic funnel and a standard pot. Now I use a

Bunn, which is a step up from the typical coffeemaker.

Our

corporate coffeemaker was generally clean due to my efforts, but most others are not.

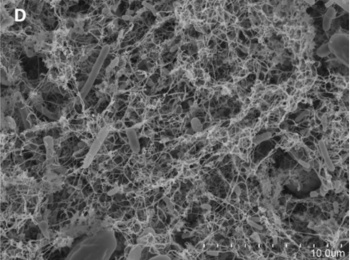

Biologists at the

University of Valencia (Universitat de València, Valencia, Spain) have

published a study on the

bacteria they found populating the coffee waste reservoirs of ten different

pod-type coffeemakers, and they also monitored the bacterial

colonization process in a new coffeemaker.[2-4]

The research team

sequenced the

ribosomal RNA of the residue, and they were able to identify 59 bacterial

genera with abundance greater than 0.01%.[3] This is a surprising result, since caffeine (

1,3,7-trimethylxanthine), a natural

alkaloid present in coffee, has

antibacterial properties.[2] As a

control check, they detected no

cultivable microorganisms or bacterial

DNA in the coffee itself, so the bacteria must have originated from the environment and grew under the warm and

moist conditions present in the coffeemaker.[2]

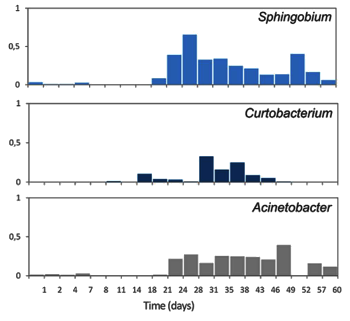

In examining the

temporal progression of bacterial

species, there appeared to be a succession from generalist bacteria to bacteria apparently

adapted to the coffeemaker

environment.[2,4] This final bacterial pool is consistent with the bacteria types normally associated with the

coffee plant and its subsequent processing.[2] In particular,

Pseudomonas bacteria, a known caffeine-degrading bacterium was found.[2,4]

The

authors advise that only careful cleaning of coffeemakers with

bacteriostatic compounds, and avoiding contact of the drip waste with other parts of the coffeemaker, will prevent possible contamination of your

beverage.[2] There might be a positive side to all this. Such bacteria might be effective in

decaffeination without the use of

solvents, and for environmental clean-up of

contaminated soil.[2,4]

Another

biohazard of coffee has been discovered by other

scientists at the University of Valencia. They detected

mycotoxins in an

analysis of a hundred commercial coffee

brands sold in

Spain by

liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).[5] Mycotoxins are

toxic chemicals produced by

filamentous fungi, and coffee can be

contaminated by mycotoxins. Interestingly, decaffeinated coffee had a higher incidence of mycotoxins than caffeinated.[5] You can worry more, or perhaps less, in the knowledge that mycotoxins are found in many other

foods, including

cereals,

dried fruit,

spices,

wine,

cocoa, and

peanut butter.[5]

References:

- Peter Schlumbohm, "Filtering Device," US Patent No. 2,241,368, May 6, 1941 (Via Google Patents).

- Cristina Vilanova, Alba Iglesias, and Manuel Porcar, "The coffee-machine bacteriome: biodiversity and colonisation of the wasted coffee tray leach," Scientific Reports, vol. 5, article no. 17163 (November 23, 2015), doi:10.1038/srep17163. This is an open access publication with a PDF file available here.

- Supplementary sequencing statistics for ref. 2.

- Matthew Braga, "Your Coffee Machine Is a Breeding Ground for Caffeine-Resistant Bacteria," Motherboard, November 26, 2015.

- Ana García-Moraleja, Guillermina Font, Jordi Mañes, and Emilia Ferrer, "Simultaneous determination of mycotoxin in commercial coffee," Food Control, vol. 57 (November, 2015), pp. 282-292.