Ballistics

December 19, 2016

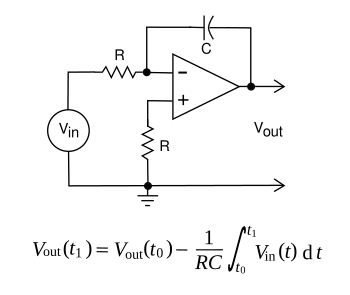

Digital computers were not the first

electronic computers. There was a span of several

decades in which

analog computers were used to solve come common problems. It's fairly easy to implement the

mathematical functions of

integration and

differentiation using

operational amplifiers, the earliest of which were built using

vacuum tubes. Notable

electrical engineer,

Robert Pease (1940-2011), who designed some early operational amplifiers while at

George A. Philbrick Researches,[1] has written many articles about their history and design.[2-4]

Since I'm a member of the

baby boomer generation, my

physics education included

laboratory exercises in

analog computation. The one exercise that I remember most is

calculating the

trajectory of a

projectile, the results of the calculation being displayed on an

x-y chart recorder. The interesting part of that exercise was seeing the difference in trajectory between a projectile launched on

Jupiter as compared with

Earth.

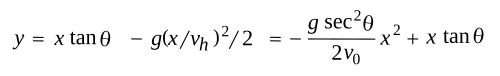

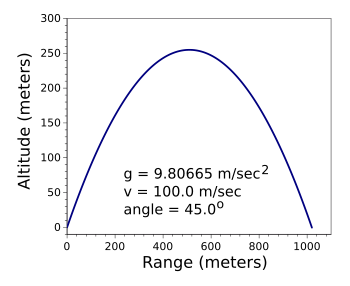

The trajectory of a projectile, idealized without

atmospheric drag,

Coriolis force, etc., has been known since the time of

Galileo, and it is derived by a simple addition of the motion arising from the projectile

velocity and that of the fall of the projectile arising from

gravity,

where (x,y) are the points that define the trajectory, θ is the launch

angle from the

horizontal, v

0 is the initial projectile velocity, v

h is the horizontal component (x component) of the projectile velocity (v

h = v

0 cos θ), and g is the

gravitational acceleration, 9.80665 m/sec

2. An example trajectory, as generated by a simple

C language program (

source code here), is shown below,

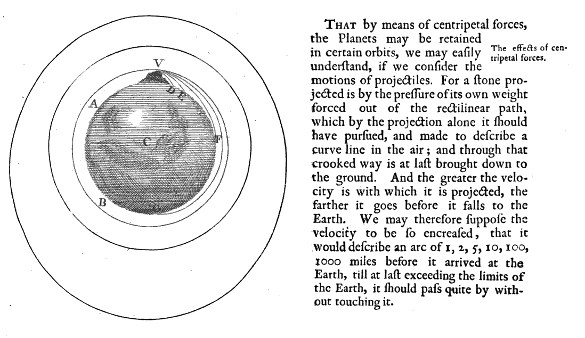

Isaac Newton used

ballistics to elucidate the idea of an

orbit of one body around another, such as the

Moon's orbiting the Earth. In his 1728 book, "

A Treatise of the System of the World," Newton imagined the

thought experiment, illustrated below, in which you

fired cannonballs at increasing velocities, finally reaching a point at which they fly into orbit around the Earth.[6] He then generalized this to the Moon's motion around the Earth.

The range

R of an ideal projectile is given as

R = (v2/g)sin(2θ), so you can hit a target at any range up to a maximum determined by the projectile's initial velocity

v by just setting the angle. It can be seen by inspection that the maximum range always occurs at an angle of 45 degrees, since the

sine of 90° is one. That angle, however, is not the angle at which the

length of the path of projectile travel is maximum.

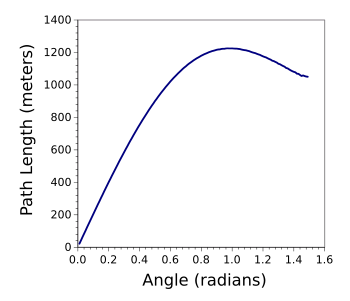

It's easy to calculate the path length of a projectile as a function of angle. You just use the trajectory example presented above and do a

piece-wise integration of the path length. My source code for such a calculation can be found

here,[6] and the results of this calculation are shown below with the maximum occurring at an angle near 1

radian (57.2958°).

Joshua Cooper and

Anton Swifton of the

Department of Mathematics of the

University of South Carolina have

published a paper on

arXiv in which they derive an

equation to give the angle that produces the maximum projectile path length.[7] This angle, which is

independent of the initial

speed of the projectile and the value of the gravitational acceleration, is the solution of this interesting equation,

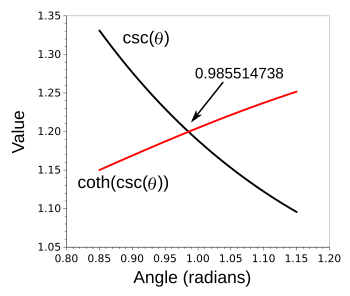

The easiest way to find the solution to an equation such as this is to use one of the many

free and open source software computer algebra systems. Cooper and Swifton used

SageMath to obtain an angle of about 0.9855 radians (56.47 degrees). I used my favorite method of refined increments (source code

here) to obtain the value 0.985514738.

References:

- GAP/R, George A. Philbrick Researches Archive.

- Application Brief R1, "Practical closed-loop stabilization of solid state operational amplifiers," Philbrick Archive, February 1, 1961.

- Bob Pease, "What's All This Transimpedance Amplifier Stuff, Anyhow? (Part 1)" Electronic Design, January 8, 2001.

- Bob Pease, "What's All This Julie Stuff, Anyhow?" Electronic Design, May 3, 1999.

- Isaac Newton, "A Treatise of the System of the World," F. Fayram, 1728, pp. 5-6.

- Thanks to Anton Swifton, who discovered an error in my original program.

- Joshua Cooper and Anton Swifton, "Throwing a Ball as Far as Possible, Revisited," arXiv, November 8, 2016.