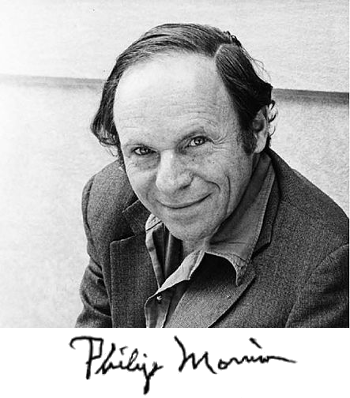

Philip Morrison

March 24, 2016 The expression, "clear as a bell," is a popular idiom. There's something about the anharmonic timbre of a bell that catches one's attention. That's why town criers, the news announcers of yesteryear, used a bell to signal their presence; why an electromechanical bell was used for nearly a century as an attention-getter on telephones; and why churches use bells to summon worshipers. Another idiom about bells is the idea of something "ringing true." A bell rings true when it's tuned to its correct pitch. From this idea we get the concept that an explanation that rings true is an explanation that's correct or believable. An explanation that your dog ate your homework doesn't ring true if the teacher knows that you don't have a dog. That's why younger siblings are at times useful. When a scientist hits upon a particularly beautiful way to explain an experiment or an observation, he says that his theory has "the ring of truth." The Ring of Truth was the title of six-part series of physics-themed television shows aired on public television in 1987 and its accompanying book.[1-2] These were authored by the preeminent physicist, Philip Morrison, and his wife, Phylis. | Physicist, Philip Morrison (November 7, 1915 – April 22, 2005), as shown in a 1976 photo. (NASA photo of Philip Morrison and his signature, via Wikimedia Commons.) |

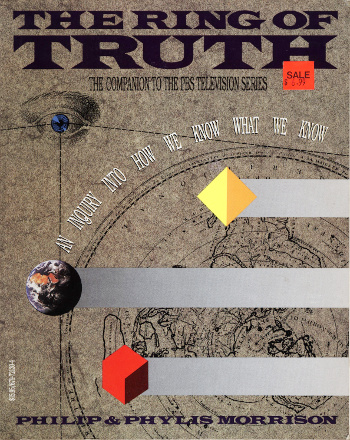

| The cover of "The Ring of Truth" by Philip Morrison and Phylis Morrison. This book was first published in October, 1987. I purchased my copy for $6.99. (Scan of my copy) |

"The title is reserved for those who have demonstrated exceptional distinction by a combination of leadership, accomplishment and service in the scholarly, educational and general intellectual life of the Institute or wider community."Morrison's paper, "On gamma-ray astronomy," appeared in Il Nuovo Cimento in 1958, and it's considered the start of gamma ray astronomy.[11] He co-authored on early paper on SETI with Giuseppe Cocconi.[12] Morrison summarized his opinion on SETI as follows:

"The probability of success is difficult to estimate, but if we never search, the chance of success is zero."[8]Morrison co-authored a 1963 paper with James Felten, one of his students, on the importance of the inverse Compton effect on the origin of high energy cosmic radiation.[8] With his first wife, Emily, he authored a 1956 book on Charles Babbage.[13] As a high school student, I learned physics from the 1962 Physical Science Study Committee (PSSC) textbook, Physics, containing several sections authored by Morrison.[8] Morrison was responsible for nearly 1500 book reviews in Scientific American.[8] I don't think that I've read that many books in my lifetime; but, perhaps, the Internet is to blame for that. Morrison was chairman of the Federation of American Scientists from 1973 to 1976, a fellow of the American Physical Society, a member of the National Academy of Sciences, and the International Astronomical Union, among other organizations. Among his many awards, Morrison was the recipient of the American Association for the Advancement of Science Westinghouse Science Writing Award, the American Institute of Physics Andrew Gemant Award, and the Astronomical Society of the Pacific Klumpke-Roberts Award.[8] One interesting Morrison anecdote involves his work on the Manhattan Project. He carried the plutonium core of the Trinity test bomb in his lap in its transit from Los Alamos to the Alamogordo test site. He said that the "core felt slightly warm, like a small cat."[8] Such radioisotope generators have now progressed from lap warmers to power supplies for spacecraft to Pluto.

References:

- Video clips from "The Ring of Truth" series by Philip and Phylis Morrison, YouTube, April 21, 2014.

- Philip Morrison and Phylis Morrison, "The Ring of Truth: An Inquiry into How We Know What We Know," Random House, October 12, 1987, 307 pp., ISBN-13, 978-0394556635 (via Amazon).

- Philip Morrison on the Internet Movie Database.

- Carl Sagan on the Internet Movie Database.

- Stephen Hawking on the Internet Movie Database.

- SX-70 (Documentary, 1972) on the Internet Movie Database.

- The Manhattan Project, Modern Marvels, Season 8, Episode 20 (June 4, 2002). Listed as Season 9, Episode 21 on Wikipedia.

- Leo Sartori and Kosta Tsipis, "Philip Morrison 1915—2005, A Biographical Memoir," National Academy Of Sciences, 2009 (0.5 MB PDF File).

- J. R. Oppenheimer, "Physics in the Contemporary World," Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, vol. 4, no. 3 (March, 1948), p. 66, as quoted in James A. Hijiya, "The Gita of J. Robert Oppenheimer," Proceedings of The American Philosophical Society, vol. 144, no. 2 (June, 2000), p. 128.

- Elizabeth A. Thomson, "Institute Professor Philip Morrison dies at 89," MIT Press Release, April 25, 2005.

- P. Morrison, "On gamma-ray astronomy," Il Nuovo Cimento, vol. 7, no. 6 (March, 1958), pp 858-865.

- P. Morrison and G. Cocconi, "Searching for interstellar communication," Nature, vol. 185, no. 4690 (September 19, 1959), pp. 844-846.

- Philip Morrison and Emily Morrison, "Charles Babbage and His Calculating Engines," Dover Publications (1961), 400 pp., ISBN-13, 978-0486200125 (Via Amazon).