Curse of the Neanderthal DNA

March 7, 2016

Neanderthal Man was a

record by the

English band,

Hotlegs. It was released on June 19, 1970, at about the time of my exit from

commercial radio broadcasting. Neanderthal Man was a reduction of

rock-and-roll music into its basic elements, so it was like the musical

analog of the

abstract art movement.[1] It had a

repetitive drum beat, and a nearly inaudible

lyric reminiscent of another song,

Louie Louie. The record was popular, selling two million copies.

It's easy to see how this record was named. The overarching drum beat evokes the image of

primitive men dancing around a

campfire; or, at least, our popular conception of what primitive men would do around a campfire. The

human subspecies,

Homo sapiens neanderthalensis, the Neanderthal Man, which became extinct around 40,000 years ago, was not that different from

modern man.

DNA analysis has shown that Neanderthal and human genomes are at least 99.5% identical.[2]

In our present age,

women swoon over

athletic males, so it's understandable that there would have been

cross-breeding between

Homo sapiens and the Neanderthal. These

subspecies derive from a

common ancestor who lived about half a million years ago, with the Neanderthal living in

Europe and

Asia and Homo sapiens staying in

Africa.[3] Such cross-breeding occurred when Homo Sapiens started to leave Africa about 100,000 years ago.[3]

Neanderthal contributions to our present genome aren't concentrated. Different people have different Neanderthal

genes, some of which aid against

infection.[3] One problem is that, unlike

fruit flies, which still cross-breed well after being separated by many thousands of

generations, sapiens and neanderthalensis were somewhat incompatible after just a few tens of thousands of generations.[3] This evokes the possibility that some Neanderthal genes were harmful in cross-breeds, and such genes were not passed along to modern man.[3]

However, some problematic genes have passed along to the present day, and these are the subject of a recent study by a large international team of

scientists.[4-7] Their

analysis is published in a recent issue of

Science.[4] Members of the

research team are associated with

Vanderbilt University (Nashville, Tennessee), the

University of Washington (Seattle, Washington), the

Mount Sinai School of Medicine (New York, New York), the

University of Washington Medical Center (Seattle, Washington),

Northwestern University (Chicago, Illinois), the

Marshfield Clinic (Marshfield, Wisconsin), the

Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota), the

National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, Maryland),

The Pennsylvania State University (University Park, Pennsylvania), the

Geisinger Health System (Danville, Pennsylvania),

Stellenbosch University (Tygerberg, South Africa), and

Case Western Reserve University (Cleveland, Ohio).[4]

Different people have different snippets of Neanderthal DNA in their genome. By sampling many modern people, about 20% of the Neanderthal genome can be found, so today's humans on every

continent are reservoirs of a varied mixture of

archaic and modern DNA.[8-9] Says

Svante Pääbo, a

paleogeneticist at the

Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in

Leipzig, Germany, who did early work on this topic, "The Neanderthal genetic contribution to present-day people seems to have larger

physiological effects than I would have naively thought."[5] Interestingly, such archaic DNA is absent from most Africans, since the cross-breeding happened outside Africa.[5]

Tracking how Neanderthal DNA affects modern humans was only possible through use of a

medical database called the

Electronic Medical Records and Genomics (eMERGE) Network which contains a patient's genetic data and medical data. This allowed

correlations to be made between genes and

symptoms for 28,416

American adults

of

European ancestry.[4-6]

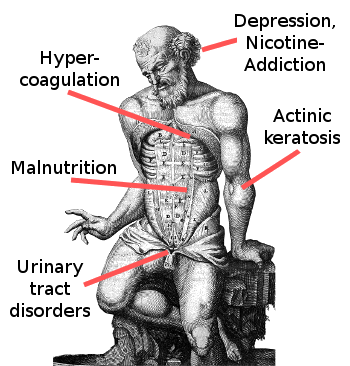

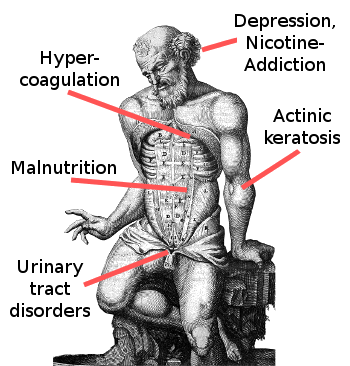

What was found is a correlation to such conditions as

actinic keratosis (

skin lesions from exposure to

ultraviolet light),

hypercoagulation,

tobacco use, and the risk of

depression.[4] Hypercoagulation would have been beneficial to Neanderthals, who lived in a dangerous

environment, since a rapid

healing of

wounds would prevent

pathogens/a> from entering the body.[5-6] For modern man, however, it results in an increased risk of blood clots and

strokes. Blood clots and strokes were not a problem for the Neanderthals, who died young.[5]

Some Neanderthal genes were found to be linked with depression and

nicotine addiction.[5-6] Quite a few snippets of Neanderthal DNA were correlated with

psychiatric and

neurological effects.[6] Other Neanderthal genes relate to an ineffective use of

thiamine (vitamin B1), which

metabolizes carbohydrates

in the

intestine. Having such Neanderthal genes might predispose people to

malnutrition.[5] Correlates to

incontinence,

bladder pain, and

urinary tract disorders were also found.[5]

| Show me where it hurts.

Human maladies associated with Neanderthal DNA.

(Base image from J. Casserius, Tabulae anatomicae LXXIXX, photo number L0022375, from the Wellcome Trust, via Wikimedia Commons.) |

Lest you think that all our genetic inheritance from the Neanderthal is all bad, two studies recently published in the

American Journal of Human Genetics have found three archaic genes that boost immune response.[5] However, even these immune system boosters have a downside of increased

allergies.[5]

References:

- Neanderthal Man by Hotlegs, YouTube video, June 17, 2010. The artists are incorrectly given as 10cc, the name of their subsequent band.

- James P. Noonan, Graham Coop, Sridhar Kudaravalli, Doug Smith, Johannes Krause, Joe Alessi, Feng Chen, Darren Platt, Svante Pääbo, Jonathan K. Pritchard, and Edward M. Rubin, "Sequencing and Analysis of Neanderthal Genomic DNA," Science, vol. 314, no. 5802 (November 17, 2006), pp. 1113-1118, DOI: 10.1126/science.1131412.

- Ewen Callaway, "Modern human genomes reveal our inner Neanderthal," Nature News,January 29, 2014.

- Corinne N. Simonti, Benjamin Vernot, Lisa Bastarache, Erwin Bottinger, David S. Carrell, Rex L. Chisholm, David R. Crosslin, Scott J. Hebbring, Gail P. Jarvik, Iftikhar J. Kullo, Rongling Li, Jyotishman Pathak, Marylyn D. Ritchie, Dan M. Roden, Shefali S. Verma, Gerard Tromp, Jeffrey D. Prato, William S. Bush, Joshua M. Akey, Joshua C. Denny, and John A. Capra, "The phenotypic legacy of admixture between modern humans and Neandertals," Science, vol. 351, no. 6274 (February 12, 2016), pp. 737-741, DOI: 10.1126/science.aad2149. This is an open access paper with a PDF file available here.

- Ann Gibbons, "Our hidden Neandertal DNA may increase risk of allergies, depression," Science, February 11, 2016.

- David Salisbury, "Neanderthal DNA has subtle but significant impact on human traits," Vanderbilt University Press Release, February 11, 2016.

- Neanderthal DNA has subtle but significant impact on human traits, YouTube video by Vanderbilt University, February 11, 2016.

- Benjamin Vernot and Joshua M. Akey, "Resurrecting Surviving Neanderthal Lineages from Modern Human Genomes," Science, vol. 343, no. 6174 (February 28, 2014), pp. 1017-1021, DOI: 10.1126/science.1245938.

- Ann Gibbons, "Revolution in human evolution," Science,vol. 349, no. 6246 (July 24, 2015), pp. 362-366, DOI: 10.1126/science.349.6246.362