Visualization in Science and Math

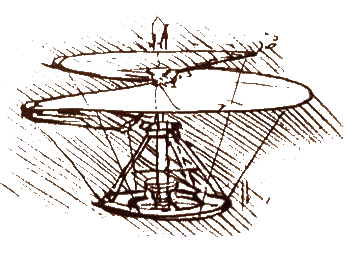

June 30, 2016 My thought processes fall into two modes. As a background process, I often churn abstract ideas in my brain for days, or weeks, at a time. However, when my thoughts are directed at more concrete ideas, I need to scratch things out with pencil and paper. In this, I'm following in the tradition of Leonardo da Vinci, who left voluminous notebooks filled with drawings. One example is his helicopter, also called his air screw, as shown in the figure. | Leonardo da Vinci's helicopter. Da Vinci, who was a keen observer of nature, may have gotten the idea for this "air screw" from the winged seeds of trees such as the maple. (Wikimedia Commons image.) |

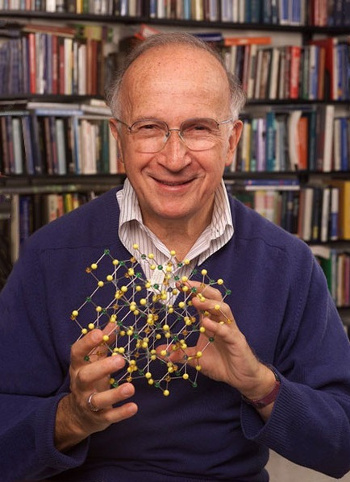

| Nobel Chemistry laureate, Roald Hoffmann, holding a ball-and-stick model of a crystal. Such models have been guiding chemists since the discovery of the atomic nature of matter. One prominent example is the elucidation of the molecular structure of DNA by James Watson and Francis Crick. (Via Wikimedia Commons.) |

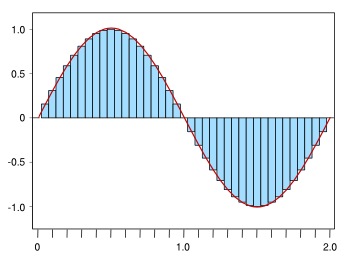

| Integral of the sine function, approximation by rectangles. The x-axis is in units of pi. The area under each half-sine wave is 2, but their sum is zero. (Created using Gnumeric.) |

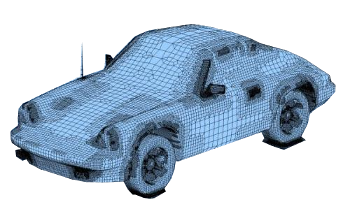

| Engineering has been assisted by computer aided design (CAD). This is a finite element model of a Porsche 911 automobile. (Modified Wikimedia Commons image.) |

|

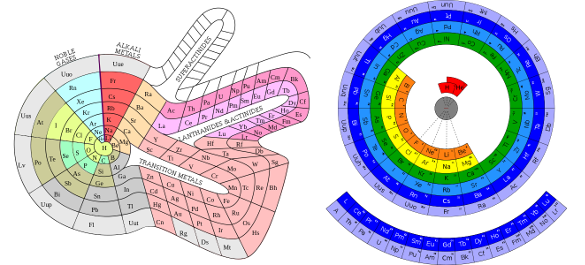

| Two spiral format periodic tables. (Click for larger versions of the left and right tables on the Wikimedia Commons Web Site. Left image by DePiep, and right image by Chris Buckley) |

"Our project is akin to the first periodic table of the elements. We have found enough of the building blocks that we can see the overall structure and begin to glimpse the underlying relationships."

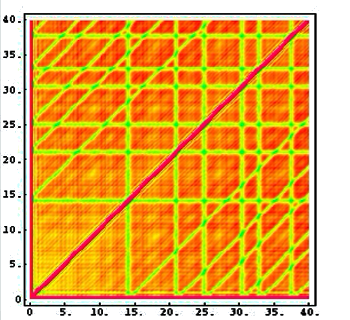

| A representation of the triple correlation of the zeros of the Riemann zeta function. The stripes arise from the influence of the first few zeros on the later zeros. (Image courtesy of Nina Snaith.) |

|

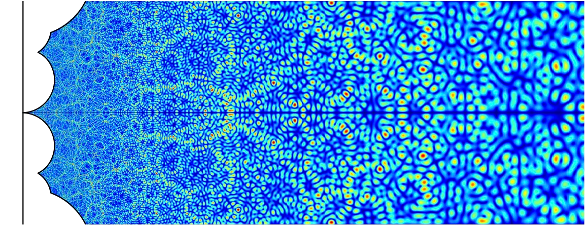

| A Maass form, one of the different types of objects in the database of L-functions, modular forms, and related objects.(Image by Fredrik Strömberg.) |

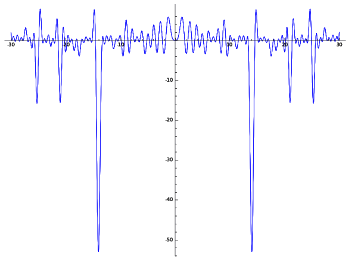

| An aural visualization can be done by mapping number values to audio frequencies. This waveform is the the Z-function of the first rank-4 elliptic curve, rendered in sound in this mp3 file. (Image courtesy of LMFDB.) |

References:

- Shaaron Ainsworth, Vaughan Prain, and Russell Tytler, "Drawing to Learn in Science, Science," vol. 333, no. 6046 (August 26, 2011), pp. 1096-1097. A PDF file of this article can be found here.

- One example, from many, is Roald Hoffmann, "The Many Guises of Aromaticity," American Scientist, vol. 103, no. 1 (January-February 2015), pp. 18ff., DOI: 10.1511/2015.112.18.

- Roald Hoffmann Web Site.

- Johan Bollen, Herbert Van de Sompel, Aric Hagberg, Luis Bettencourt, Ryan Chute, Marko A. Rodriguez and Lyudmila Balakireva, "Clickstream Data Yields High-Resolution Maps of Science," PLoS ONE, vol. 4, no. 3 (March 11, 2009), article e4803, http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0004803. The scientific field map can be found at this link.

- Exploring the mathematical universe - Uncovering new worlds along the way, American Institute of Mathematics, May 10, 2016.

- LMFDB, the database of L-functions, modular forms, and related objects.