George Westinghouse

June 16, 2016

As

Mark Twain supposedly said, "I have never let my

schooling interfere with my

education." However, the evidence for Twain's saying this is slight, and it's thought that the attribution should be to

novelist and

essayist,

Grant Allen.[1]

No matter who said it, it appears to have held true for many notable individuals, including

Bill Gates, a

self-taught computer programmer, and a famous

Harvard University drop-out. About a

century earlier than Gates,

George Westinghouse, Jr., (1846-1914) dropped out of

Union College (Schenectady, New York) in his first term to create a series of

inventions and an

industrial empire.

Westinghouse was born in

Schoharie, New York, quite near to

Schenectady and Union College. His father, George Westinghouse, Sr., owned a

machine shop where the younger George became adept at

designing and making

machinery. After spending some time in

military service in the

New York National Guard and the

New York Cavalry during the

Civil War, he found service in the

US Navy as an

engineer on a

gunboat through the war's end.

It was after the war, in 1865, when he returned to civilian life, that he attended Union College for that short period. At that point, he began his career as an inventor, inventing

steam-powered engines, such as the

Westinghouse Farm Engine, and railroad equipment.[2] As I wrote in a

previous article (Bacterial Signature, November 12, 2015), steam engines of all sorts were ubiquitous in that period, as were

steam locomotives in

rail transport.

In 1869, after seeing a

train wreck caused by the primitive

braking system used at the time in which brakes were local to each rail car and not centrally controlled, Westinghouse invented his

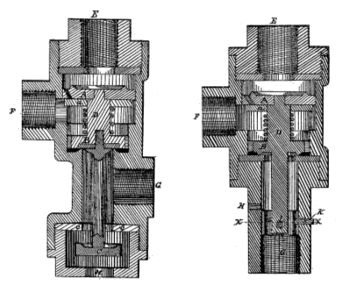

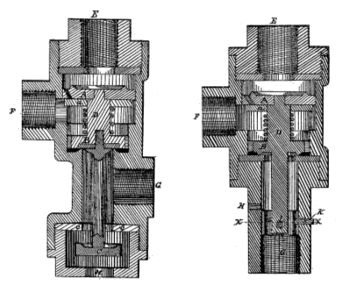

compressed air braking system for rail cars. As detailed in his 1873

patent (see figure), a locomotive engineer could apply brakes to all rail cars simultaneously.

| Figures one and two from US Patent No. 144,006, 'Improvement in steam and air brakes,' by George Westinghouse, Jr., October 28, 1873.

(Via Google Patents.[3]) |

The system had a

safety feature in which the compressed air actually disengaged the brakes, so any failure of the compressed air supply would result in immediate braking. These brakes, which became ubiquitous on rail cars, were manufactured and sold by the

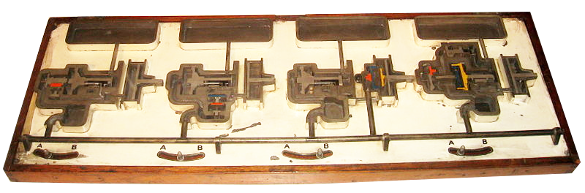

Westinghouse Air Brake Company. Westinghouse leveraged his railroad connections to produce and market other railroad devices, such as

railway signals. He founded the

Union Switch & Signal Company to manufacture and sell such devices.

After

Edison's perfecting the

incandescent light bulb and building the first

electric power station in

lower Manhattan in the period 1879-1882, Westinghouse realized the

commercial importance of

electrical technology. Seeing that he could make more money by developing a potentially better

alternating current (AC) electric system to compete with Edison's

direct current (DC) system, he hired

physicist,

William Stanley, to investigate AC circuitry in Pittsburgh. I wrote about the advantages of AC power distribution in reducing

power losses in transmission lines in a

previous article (Ionized Air, July 9, 2015).

Westinghouse and Stanley installed their first AC power system in

Great Barrington, Massachusetts, in 1886. Power was derived from a 500

volt hydroelectric generator stepped up by

transformer to 3,000 volts for transmission. At the end of the transmission line, transformers stepped the voltage down to 100 volts to supply

electric lights. The year, 1886, also marked the founding of the Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company. The company name was shortened to

Westinghouse Electric Corporation in 1889.

Any article about AC power systems must mention

Nikola Tesla. Westinghouse

licensed Nikola Tesla's US patents for

induction motor and transformer designs in 1888. This was followed by AC lighting of the

1893 World's Columbian Exposition in

Chicago, for which Westinghouse outbid Edison's

General Electric. The Columbian Exposition demonstration was an important factor in the decision to have Westinghouse build the

Adams Power Plant at

Niagara Falls in 1895.

Westinghouse had close ties to the city of

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, having moved there in 1869 and eventually living in the

Homewood section of the city. Brady Smith, senior communications manager of the

Heinz History Center (

www.heinzhistorycenter.org) recalls several details of his life there in a recent article.[4] Since he had been a working man at his father's company, he understood the drudgery of the customary six day

work week, so in 1881 he gave his

employees a half-day off on

Saturdays.[4]

Natural gas wells in

Pennsylvania are not just a modern phenomenon associated with

fracking. Westinghouse drilled a gas well in his backyard in 1884 so he could have a supply of that

fuel for

experiments. As a result, he founded the first commercial gas company in Pittsburgh.[4] Westinghouse lost control of Westinghouse Electric after the

financial crisis of 1907, and by 1911 his

health was failing, and he was no longer active in business.[4]

At his death in 1914, Westinghouse left a legacy of 60 founded companies with 15,000 patents and 50,000 worldwide employees.[4] His

boyhood home in Schoharie, New York, is listed on the

National Register of Historic Places.

References:

- Never Let Schooling Interfere With Your Education - Mark Twain? Grant Allen?, Quote Investigator, September 25, 2010.

- According to Wikipedia, Henry Ford enjoyed working with a Westinghouse Farm Engine on a farm, and he even worked as a mechanic for these farm engines for the Westinghouse Company.

- George Westinghouse, "Improvement in steam and air brakes," US Patent No. 144,006, October 28, 1873.

- Brady Smith, "Let's learn from the past: George Westinghouse," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 21, 2016.

- George Westinghouse Biography, Engineering and Technology History Wiki.