Mathematical Astronomy in Babylon

March 10, 2016 My science education started with children's science books. One of these was "The World of Science," and another was the "Golden Book of Science."[1] The full title of the latter book was, "The Golden Book of Science for Boys and Girls." The author of that book was a woman, Bertha Morris Parker, and this probably explains such an early excursion into gender equality in the sciences. The premier children's mathematics book of my generation was Irving Adler's, "The Giant Golden Book of Mathematics," Illustrated by Lowell Hess (Golden Press, New York, 1960).[2] | The Golden Book of Science for Boys and Girls by Bertha Morris Parker (1956). This profusely illustrated book was an inspiration for many young scientists. It's interesting how far science has advanced in the sixty years since publication of this book. (Scan of the cover of my copy.)[1] |

| Ancient Wonder | Date | |

| Great Pyramid of Giza | 2584–2561 BC | |

| Hanging Gardens of Babylon | c. 600 BC | |

| Temple of Artemis at Ephesus | c. 550 BC | |

| Statue of Zeus at Olympia | 466–456 BC | |

| Mausoleum at Halicarnassus | 351 BC | |

| Colossus of Rhodes | 292–280 BC | |

| Lighthouse of Alexandria | c. 280 BC |

.jpg) | The Hanging Gardens of Babylon, as painted in 1886 by Ferdinand Knab (1834-1902) as part of his "Seven Wonders of the Ancient World" series. (Via Wikimedia Commons.) |

|

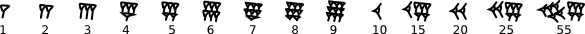

| Some representative Babylonian numbers, illustrating how quantities were inscribed by a simple wedge-tipped stylus into clay tablets. fractional numbers, as given in modern notation, have the form a; b, c, d, which has the decimal equivalent a + (b/60) + (c/3600) + (d/603), etc. (Modified Wikimedia Commons image by Josell7.) |

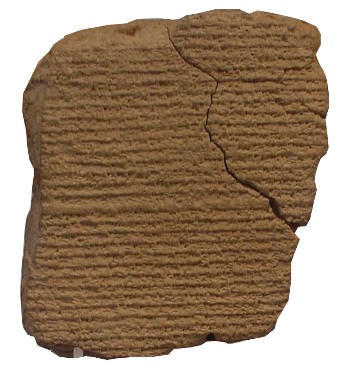

| Perhaps it was practice in deciphering the hen-scratching of students that enabled the deciphering of this tablet. A Babylonian tablet, now at the British Museum in London, recording the appearance of Halley's comet in 164 BC. (Photograph by Linguica, via Wikimedia Commons.) |

| The Babylonian god, Marduk, as found on a cylindrical seal. Marduk, who is associated with the planet, Jupiter, is shown on the seal with his pet dragon, sirrush. Zeus, the principal deity of the ancient Greeks, and Jupiter, the principal deity of the Romans, were also identified with the planet Jupiter. (Modified Wikimedia Commons image.) |

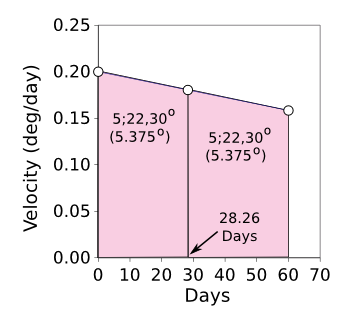

| Equal area construction for the motion of Jupiter. The areas are given in sexagesimal notation and their decimal equivalent. (Created from data in ref. 3 using Gnumeric and Inkscape.[3]) |

References:

- Bertha Morris Parker, "The Golden Book of Science for Boys and Girls (A Giant Golden Book)," Simon and Schuster, January 1, 1956, 97 pp. (via Amazon).

- Irving Adler, "The Giant Golden Book Of Mathematics: Exploring The World Of Numbers And Space," illustrated by Lowell Hess, Golden Press, January, 1960, (via Amazon).

- Mathieu Ossendrijver, "Ancient Babylonian astronomers calculated Jupiter's position from the area under a time-velocity graph," Science, vol. 351, no. 6272 (January 29, 2016), pp. 482-484, DOI: 10.1126/science.aad8085.

- Ron Cowen, "In Depth - Archaeology - Ancient Babylonians took first steps to calculus," Science, vol. 351, no. 6272 (January 29, 2016), p. 435, DOI: 10.1126/science.351.6272.435.

- Michelle Hampson, "Ancient Babylonians Used Advanced Geometry to Track Jupiter," AAAS News, January 27, 2016.