Tiling

September 24, 2015 Every technological age can be identified by its materials. For the Industrial Revolution, these were primarily iron and coal. The computer age is linked with silicon, but my childhood seemed to be the age of linoleum. Linoleum, named for its principal ingredient, linseed oil, was invented in 1855, but its popularity as a floor tile peaked in the 1950s. The corridors of my elementary school were a sea of square linoleum tiles, chosen for that purpose because they were very easy to clean. Complete coverage of a surface is called tiling. There are a multitude of ways to tile planar surfaces with geometrical shapes. Although the floor tiles of my school were square, nature seems to prefer hexagonal tiling, as shown in the figure. Humans have mimicked nature by using hexagons for tiling. |

| Left image, graphene; middle image, honeycomb; and right image, hexagonal pavement tiles by Claudine Rodriguez; all via Wikimedia Commons. |

| The pattern of blocks for my patio. This is a very common tiling for rectangles whose length is twice the width, and it can be visualized as a shading of a square tiling. (Photo by author) |

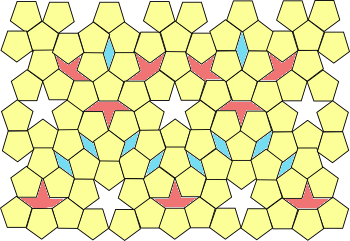

| Keplerian pentagonal tiling. (Created with Inkscape.) |

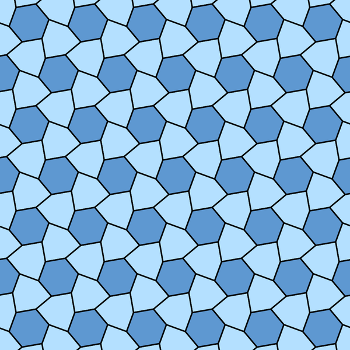

| Tiling hexagons with another six-sided figure. (Illustration by Tadeusz E. Dorozinski, via Wikimedia Commons.) |

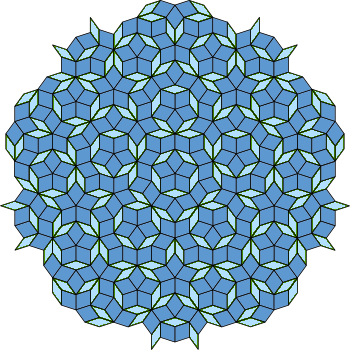

| A Penrose rhombus tiling with five-fold rotational symmetry. Roger Penrose was issued a patent on his tiling in 1979.[3] This patent, which has now expired, gives directions for creating such tilings. (Modified Wikimedia Common image). |

"We discovered the tile using using a computer to exhaustively search through a large but finite set of possibilities... We were of course very excited and a bit surprised to find the new type of pentagon."[6]

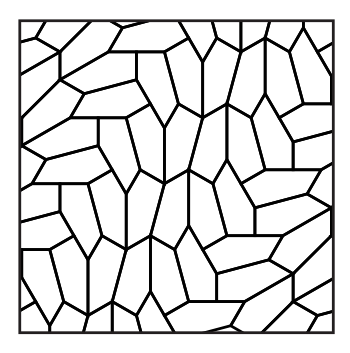

| The 15th pentagonal tiling, published in August, 2015, by Casey Mann, Jennifer McLoud, and undergraduate researcher, David Von Derau, of the University of Washington Bothell. (Modified Wikimedia Commons image by Ed Pegg, Jr.) |

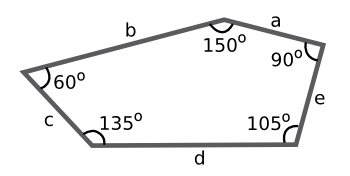

a=c=e

b=2a

d = 2a/((√2)((√3)-1))

| The pentagonal tile used in the newly-discovered planar tiling. (Wikimedia Commons image by Tom Ruen, modified using Inkscape.) |

References:

- Johannes Kepler, "Harmonices Mundi," 1619, from the Carnegie Mellon University Posner Collection.

- Craig Kaplan, "The trouble with five," Plus Magazine, December 1, 2007.

- Roger Penrose, "Set of tiles for covering a surface," US Patent No. 4,133,152, January 9, 1979 (via Google Patents).

- Discovery rocks the math world, University of Washington, Bothell, Press Release, August 14, 2015.

- Eyder Peralta, "With Discovery, 3 Scientists Chip Away At An Unsolvable Math Problem," NPR, August 14, 2015.

- Alex Bellos, "Attack on the pentagon results in discovery of new mathematical tile," The Guardian (UK), August 25, 2015.