Parchment DNA

February 26, 2015 As Marshall McLuhan so famously stated, "the medium is the message." He reasoned that the medium influences the perception of content, and I notice that when I compare movies with the books on which they're based. Some scientists from Trinity College Dublin have taken this saying literally, as they have been examining DNA and protein from the parchment of documents written in the 17th and 18th centuries.[1-3] Parchment is a writing material made from the skin of animals, such as sheep and calves. Parchment was used as a writing medium more than two thousand years ago. The Dead Sea Scrolls were written on ibex and goat parchment. Even after the widespread use of paper, parchment was reserved for important documents for which common paper was deemed too impermanent. | A parchment dated April 2-15, 1742, from Vicars Choral Estates. (Trinity College Dublin Image, by permission of the Borthwick Institute for Archives.) |

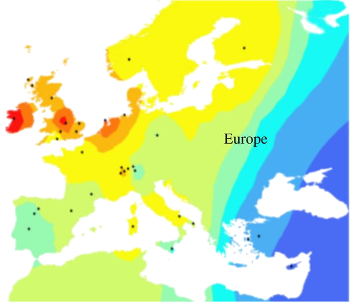

"Wool was essentially the oil of times gone by, so knowing how human change affected the genetics of sheep through the ages can tell us a huge amount about how Agricultural practices evolved."[2]Parchment is an unique DNA reservoir, since, unlike bone remains, it has been carefully preserved above ground in a controlled environment.[1-2] Bone remains contain high levels of bacterial DNA and low levels of the DNA from whence they came.[1] Small (2 cm by 2 cm) specimens were obtained from parchments at the Borthwick Institute for Archives of the University of York. These specimens were used for both DNA analysis and for mass spectrometric analysis of extracted collagen.[1-2] One parchment was linked to the black-faced breeds of northern Britain, while the other had a closer affinity with Midland and southern Britain where livestock improvements were common in the later 18th century.[2]

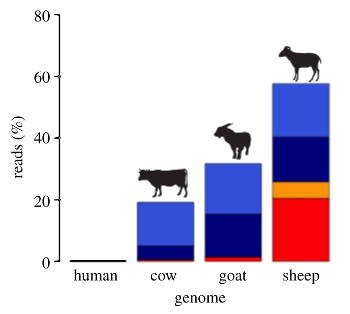

| Histogram of raw sequence read alignments (see reference for color codes) that indicate a match to the sheep genome for one of the two parchments in the study. (Fig. 1(a) from ref. 1, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License.)[1] |

"We believe the two specimens derive from an unimproved northern hill-sheep typical in Yorkshire in the 17th century, and from a sheep derived from the 'improved' flocks, such as those bred in the Midlands by Robert Bakewell, which were spreading through England in the 18th century. We want to understand the history of agriculture in these islands over the last 1,000 years and, with this breath-taking resource, we can."[2]

| A synthetic map of how the genome of one parchment matches the genotypes of modern breeds. "Warmer" colors indicate a better match. (Fig. 2(b) from ref. 1, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License.)[1] |

References:

- M. D. Teasdale, N. L. van Doorn, S. Fiddyment, C. C. Webb, T. O'Connor, M. Hofreiter, M. J. Collins, and D. G. Bradley, "Paging through history: parchment as a reservoir of ancient DNA for next generation sequencing," Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 370, no. 1660 (January, 2015), DOI: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0379. This is an open access publication with a PDF file available here.

- Thomas Deane, "Scientists reveal parchment's hidden stories," Trinity College Dublin Press Release, December 8, 2914.

- Scientists Reveal Parchment's Hidden Stories, Trinity College Dublin and the University of York YouTube Video, December 8, 2014.