Impact Diamonds

January 26, 2015 Diamonds Are Forever is a 1971 James Bond film staring Sean Connery.[1] The title comes from the popular notion that diamonds are indestructible. Diamonds, like other carbon allotropes, will actually burn. As I outlined in a previous article (Making Diamonds, December 16, 2013), the Gibbs free energy shows that oxidation is favored even at room temperature; viz.,[2]C(Diamond) + O2(gas) -> CO2(gas)The negative sign indicates a favorable reaction. However, an activation energy must be overcome before the reaction initiates. For this reason, diamond will only ignite at a temperature of 850-1,000 °C in air, or 720-800 °C in pure oxygen. Theory is one thing, but scientists are skeptical people, and they require proof in the form of an experiment. In 1772, Antoine Lavoisier used a lens to focus the Sun's rays onto a diamond in an oxygen atmosphere to heat it sufficiently to produce carbon dioxide. Diamond is the stable allotrope of carbon only under high pressure, as its Phase Diagram shows (see figure). Fortunately for jewelers, once diamond is formed it will exist metastably at room temperature. Natural diamonds form from carbonaceous minerals at extreme depths (about a hundred miles) within Earth's mantle where such high pressures exist. This process was completed only after a considerable fraction of the age of the Earth had passed. The diamonds thus formed were transported to the surface by volcanic eruptions in which they are embedded in igneous rock, such as kimberlite.

ΔGf(Diamond) = 0.693 kcal/mole

ΔGf(Oxygen) = 0 kcal/mole

ΔGf(Carbon Dioxide) = -94.258 kcal/mole

ΔG(Reaction) = -94.951 kcal/mole

| The carbon phase diagram. The triple point (TP) is around 4600 K and 10.8 MPa. (Wikimedia Commons image, from data in ref. 3, modified using Inkscape.)[3] |

| There goes the neighborhood! An artist's impression of the Cretaceous-Tertiary (K-T) meteor impact event, now known as the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) impact event. This meteor impact, 65 million years ago, is thought to have been responsible for dinosaur extinction. (Image: Don Davis/NASA, via Wikimedia Commons.) |

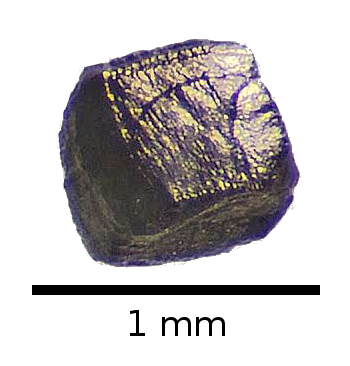

| This "lonsdaleite" grain from the Canyon Diablo meteorite looks more like coal than diamond. The scale bar is one millimeter. (Photograph: Arizona State University/Laurence Garvie, cropped and annotated.)[5] |

|

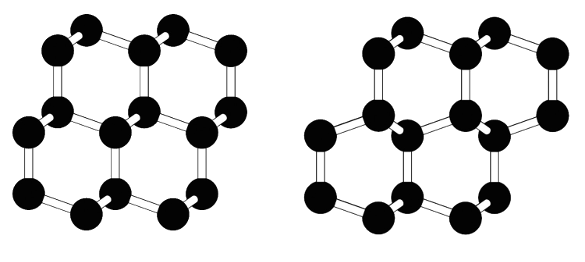

| The crystal structure of diamond (left), and the presumed structure of lonsdaleite (right). The carbon atoms are tetrahedrally-bonded in each, but the overall structure shows a subtle difference between alternate layers of carbon atoms. (Arizona State University image by Péter Németh.)[5] |

References:

- Diamonds Are Forever (1971, Guy Hamilton, Director) on the Internet Movie Database.

- Free energy data from L. B. Pankratz, "Thermodynamic Properties of Elements and Oxides," U. S. Bureau of Mines Bulletin 672, U. S. Government Printing Office (1982).

- J.M. Zazula, "On Graphite Transformations at High Temperature and Pressure Induced by Absorption of the LHC Beam," LHC Project Note 78, CERN, January 18, 1997 (PDF File).

- Péter Németh, Laurence A. J. Garvie, Toshihiro Aoki, Natalia Dubrovinskaia, Leonid Dubrovinsky, and Peter R. Buseck, "Lonsdaleite is faulted and twinned cubic diamond and does not exist as a discrete material," Nature Communications, vol. 5, Article No. 5447 (November 20, 2014), doi:10.1038/ncomms6447.

- Asteroid impacts on Earth make structurally bizarre diamonds, say ASU scientists, Arizona State University Press Release, November 20, 2014.