The Color, Blue

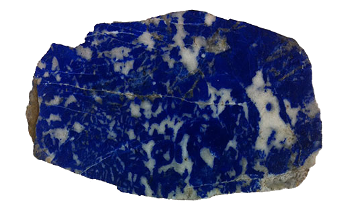

February 9, 2015 Because of my Italian ancestry, my veins are not that visible beneath my dark skin. However, fair-skinned people have visible veins, and that's apparently where we get the term, "blue blood," to denote aristocracy. Today, however, the skin of the average one-percenter has become somewhat darker, so "blue-blood" is destined to become an archaic term. The color, blue, is used to signify a melancholy mood, and the word appears often in popular culture. The following is a list of a few popular songs with blue in their titles. I selected ones that are most familiar to me, and I played many of these in my short, pre-scientific, career as a top-40 DJ. window will confirm that half our visible world is blue, at least on the nicer days. Artists and artisans have added blue to their palette through the use of several natural pigments. The most historically famous of these is ultramarine (Na8-10Al6Si6O24S2-4), first obtained by grinding the mineral, lapis lazuli. Lapis lazuli was imported into Renaissance Europe from Afghanistan, so ultramarine was expensive until its chemical synthesis in 1826. | Lapis lazuli was first mined in Afghanistan, circa 4500 B.C.[1] (Northwestern University image.) |

| Azurite specimen in the Melbourne Museum. (Photo by Graeme Churchard, cropped, via Wikimedia Commons.) |

Cu2CO3(OH)2 + 8SiO2 + CaCO3 -> CaCuSi4O10 + 3CO2 + H2OOften, a small quantity of sodium carbonate was added to aid in the fusion of the reactants.

| Laboratory synthesis of Egyptian blue pigment by firing sodium carbonate, quartz, malachite and calcite (right). (Northwestern University image.) |

| Mrs. Stewart's Bluing, first produced in 1883, was a fabric bluing agent made with Prussian blue. I remember doing chemistry experiments with my mother's laundry bluing in the 1960s. (Photo by Joe Mabel (modified), via Wikimedia Commons.) |

| Cobalt blue dish, Europeans Playing Musical Instruments, Qing dynasty, Kangxi period (1661-1722). (The Art Institute of Chicago, Bequest of Henry C. Schwab, via Northwestern University.) |

Cu2CO3(OH)2 + 8SiO2 + 2BaCO3 -> 2BaCuSi4O10 + 3CO2 + H2OYou can see that this is the barium analog of the Egyptian blue reaction, using barium carbonate instead of calcium carbonate. Marc Walton, a senior scientist at the Northwestern University, Art Institute of Chicago, Center for Scientific Studies in the Arts, has been intrigued by blue pigments for the past fifteen years.[1] It started when Walton, as a graduate student, found that the word, "blue," didn't appear until centuries after the first blue pigment, Egyptian blue, appeared.[1] Blue has a special place in pigments, since the color appears often in nature, but it doesn't appear that often in minerals.[1] The Egyptians made extensive use of blue, but Roman art used very little blue; so, the art of manufacturing blue pigment was lost.[1] Around the 6th century A.D., only lapis lazuli was used as a blue pigment, but it was used sparingly because of its cost.[1] Azurite became a cheaper blue pigment, and it was generally used as a foundation layer for the more vibrant lapis lazuli pigment. In modern times, Prussian blue was used by Picasso, and synthetic chemistry has given us many blue pigment alternatives.[1]

References:

- Megan Fellman, "Who Knew There Was so Much to Blue? - Scientist studies blue's invention and reinvention throughout history," Northwestern University Press Release, November 5, 2014.

- The Natural History of Pliny, John Bostock and H.T. Riley, Trans., (H. G. Bohn: New York, 1857), vol. 6, chap. 57 (via Google Books).