The Cosmology of Edgar Allan Poe

July 6, 2015 Our distant ancestors certainly wondered about the objects in the night sky; and, over the course of time, the more imaginative of them conjectured about the nature of these objects, and the nature of the world, itself. While they had some rudimentary observations, such as the cycle of days and nights, and the shifting position of the Moon, their cosmology was of a speculative sort, more like that of a philosopher than a scientist. Cosmology, from the Greek kosmos (κοσμος, "world") and logia (λογια, "study of"), is the study of the origin and working of the universe. While scientists have now overwhelmed this field of study, it was once the sole province of theologians and philosophers. Some vestige of philosophical cosmology lingers in our scientific world, one example being the eschatological writings of Teilhard de Chardin (1881-1955). One early model of the universe, devised by the Babylonians, pictured a flat Earth floating in the "waters of chaos," with the dome of heaven protecting Earth from being overwhelmed by these waters. Since rock doesn't float, the Hindu's decided that the Earth was carried by a turtle floating on that vast sea. Since balancing the Earth on a turtle shell is problematic, there are elephants who stand on the turtle to carry the Earth (see figure). | The Hindu model of the universe. (An illustration from Popular Science Monthly, volume 10, 1876, via Wikimedia Commons.) |

| Mosaic of Atlas in a subway station. (Detail of a photo by K.A. Stepanov, via Wikimedia Commons.) |

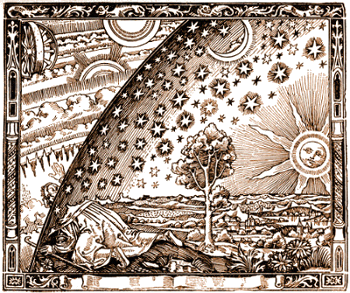

| A medieval pilgrim crossing the sphere of the fixed stars. A wood engraving from Camille Flammarion's L'Atmosphere: Météorologie Populaire (Paris, 1888), p. 163. (Via Wikimedia Commons.) |

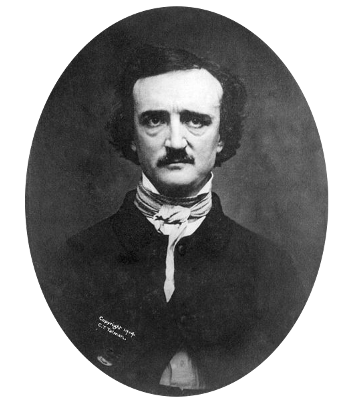

| Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) This daguerreotype of Poe was taken by Edwin H. Manchester in the same year as Poe's "Eureka" lecture. (From Michael J. Deas, "The Portraits and Photographs of Edgar Allan Poe," University Press of Virginia, 1988, p. 40, via Wikimedia Commons.) |

"It is, I think, the work of a man trying to reconcile the science of his time with the more philosophical and spiritual cravings of the mind. Poe, besides being fairly well-informed in science and mathematics, seems to have had the mind of a mathematician, and consequently was not to be put off with vague phrases; and made a creditable attempt to introduce precision of thought... I should say then that regarded as an attempt to put forward a new physical theory, Eureka would rightly be regarded as a crank-theory by scientists of the time. (The trouble with cranks is usually, not that they are not far-seeing, but that they have no appreciation of the immediate obstacles in the road.) Poe's more definite suggestions... were not unintelligent but amateurish."Alberto Cappi has written previously about Poe's Eureka.[4-5] Cappi and coauthor, Paolo Molaro, write that Poe was the first to imagine a Newtonian evolving Universe.[2] The fact that the universe is evolving was only established in the early 20th century with Edwin Hubble's discovery of universal expansion. Poe reasoned that a static universe would have collapsed upon itself because of gravity. In Eureka, Poe discussed Olbers paradox, and the existence of galaxies other than the Milky Way. The realization that nebula are really galaxies did not occur until 1920, more than seventy years after the publication of Eureka. The astronomy at the time of Eureka's writing was essentially just planetary stellar astronomy with some study of the "nebulae." John Herschel (1792-1871) and Friedrich Bessel (1784-1846) were the prominent astronomers of the early 19th century, and the planet Neptune was discovered in 1846. There was some evidence of structure in the nebulae, but it was not until the later part of the century that the spiral structure of Messier 101, the Pinwheel Galaxy, was observed and sketched. The idea of an infinite universe was philosophically repugnant to Poe since it requires unlimited matter.[2] Poe uses Olbers paradox, which I wrote about in a previous article (Stardust, August 20, 2014), to reject the idea of an infinite universe. Poe accepts Herschel's estimate of the size of the universe, about three million light years.[2] Building on the idea that the universe is finite, Poe writes that the number of stars is less than the number of atoms in a cannon ball. A middle-sized cannon ball weighs 18 pounds (about 8 kilogram). Since the gram molecular weight of iron is 55.845 grams, a cannon ball contains about 143 moles of atoms, or 8.63 x 1025 atoms. Our known universe contains about 1022 stars, an estimate obtained by multiplying its 100 billion galaxies by 100 billion stars per galaxy, so Poe's inequality still holds true. Poe intuitively conjectured the hierarchical structure of the universe in his appeal to Newton's gravitation when he writes, "There is nothing to impede the aggregation of various unique masses, at various points of space."[1] Poe imagined the universe to be a spherical cluster of galaxies separated by voids; or, as he termed it, "immeasurable vacancies in space."[1] Poe believed our universe to be just one of many; viz.,

"There exist a limitless succession of Universes more or less similar to that we have cognizance. Add to this: If such clusters of clusters exist, however -- and they do -- it is abundantly clear that, having had no part in our origin, they have no portion in our laws. They neither attract us, nor we them... Among them and us -- considering all, for the moment, collectively -- there are no influences in common."[1-2]Before I close, I'll mention one of my favorite science fiction television series - Eureka, which ran for many years on the Syfy network, previously known as the "Sci-Fi Channel." While this cable network is known for its silly, made-for-television, science fiction films that notoriously trash all the science, Eureka was well scripted. There was also good character development that made it interesting beyond the science.

References:

- Edgar Allan Poe, "Eureka: A Prose Poem," Geo. P. Putnam (New York, 1848), via Project Gutenberg.

- Paolo Molaro and Alberto Cappi, "Edgar Allan Poe: the first man to conceive a Newtonian evolving Universe," arXiv, June 17, 2015.

- Letter of Eddington to Arthur Hobson Quinn about Eureka, from "Edgar Allan Poe: a critical biography," by Arthur Hobson Quinn (Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1941), pp.555-556. Available on Amazon, here.

- Alberto Cappi, "Edgar Allan Poe And His Cosmology," December 1, 2005.

- Cappi, Alberto, "Edgar Allan Poe's Physical Cosmology," Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society, vol. 35 (June, 1994), pp. 177-192. The full paper is available as a PDF file at this link.